Wild Sea, Protected Land

Península Mitre is now protected, thanks to the work of a committed community.

To Juan and Nacho, for showing me Península Mitre.

On December 6, 2022, Tierra del Fuego’s legislative body unanimously passed a law that created Península Mitre Natural Protected Area, located at the southernmost tip of South America. With this declaration, the result of over 30 years of work, this refuge for wonderful wild nature—a key carbon sink for the world and home to impressive concentrations of peat—also becomes one local community’s triumph with global relevance.

My story with Península Mitre began 10 years ago, when my friends Juan and Ignacio from the expedition group Estudios Patagónicos took me there to film my first movie, Finibusterre: Latitud 55° Sur. That’s when I first discovered this fascinating place that became engraved in my memory. Península Mitre starts where the roads end.

I remember when we arrived at Bahía Aguirre, the most prominent inlet at the southernmost point of Mitre. The closer we got to the old, abandoned Puerto Español ranch, the wider the Bonpland River became. We saw a herd of wild horses, shaking their long manes in the wind, as they crossed the river, marking its depth and importance as our crossing point. To reach our destination, we got into the water fully dressed, then continued on toward the cozy warmth of the fire stove in the last-standing ranch building, now turned into a shelter.

An autumn snowfall at the mouth of the Bonpland River. Puerto Español, Bahía Aguirre, Península Mitre. Photo: Joel Reyero

In the landscapes of Península Mitre, the mountains collide with the sea, while unpredictable tides, dense impenetrable forests and treacherous trails force you to constantly seek alternative routes. It is a wild environment where a surprising variety of species coexist, creatures that stare with curiosity as you pass by. That’s where we wandered for 31 days collecting stories from past settlers like Don Pedro Ostoich, who lived in this area in total solitude for 12 years, and then with his wife for eight more years during the first half of the 20th century. In the documentary, we hear his voice from tapes he recorded to share stories of the two decades he’d spent in this corner of the planet. “Today, those ranches are abandoned, and virgin nature is defending itself so that humans do not abuse it.” With the distinctive cadence of the old Fuegians, Pedro portrayed this as a place where any extractive ventures seemed destined to sink.

Felipe Cancino looks for the best path through the dense forests of Península Mitre. Photo: Rodrigo Manns

Since 1984, various government agencies, civil society organizations as well as academic and scientific sectors have sought to protect the peninsula to safeguard its heritage values. When Tierra del Fuego was still not a province, back in 1989, the first director of the regional museum, Oscar Zanola, proposed the creation of a cultural and natural reserve. Many ups and downs later, in 2017, the government of Tierra del Fuego summoned several organizations and the local community to jointly develop a new environmental project, one that included the protection of the surrounding waters of the peninsula and the Isla de los Estados. In December 2020, the province declared Península Mitre of environmental, natural and cultural interest. Politically, the path was cleared for the enactment of a law that would protect the area from short-term productive activities so that no harm could be done to these landscapes.

During all that time, the society in Tierra del Fuego became more and more committed to the protection of the peninsula. In recent years, decision-makers have seen both school kids and scholars advocating for the importance of this law. The activism endeavors of different environmental organizations played a crucial role inviting people to add their voices to this cause, and over time it was the local community who became the primary advocate for Mitre’s cultural and ecological values. That was precisely the missing link, because the only explanation for the more than three decades of delay in passing this law was the lack of awareness about the values that needed protection.

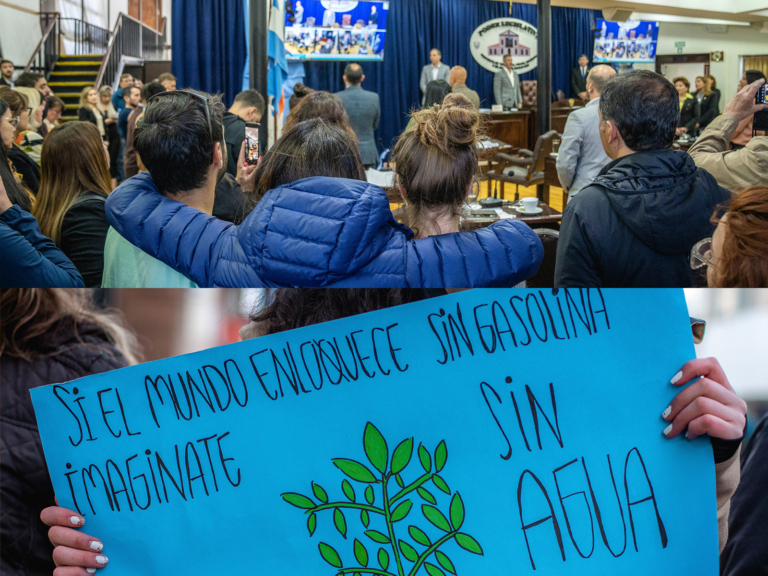

Top: A hug for victory. Members of different environmental organizations and community representatives witness history as Península Mitre Natural Protected Area is signed into law. Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego.

Bottom: The protection of Península Mitre was a community effort and a citizen’s triumph. Children, adults, academics and ordinary people each did their part. Photos: Joel Reyero

While researching Mitre’s environmental history, I met several of those local activists. One of them is Nahuel Stauch, a Fuegian that works as a mountain and fishing guide in the peninsula. Nahuel says that his activism, “arose as a result of many years touring the area on horseback, fishing and walking to explore every possible corner of this wonderful place.”

For him, he says, “the approval of the law creates that necessary protection framework so that the state can have a more active presence in the place, and we are not solely responsible for taking care of it as individuals.” However, he is careful when looking to what’s next: “There’s still much to be done by the community in the coming years to make the Península Mitre Natural Protected Area something solid.”

Just like Nahuel, many Fueguians—locals by birth or adopted by the territory—whether they are members of activist organizations or not, groups of friends, or individuals motivated by their connection to the land, have developed a sense of belonging that gives the peninsula an identity of its own and has turned its residents into advocates, each in their own way. This heartfelt relationship has created distinctive characters, such as El Paisa, a countryman who has lived in Península Mitre for years and generously welcomes visitors to his ranch, people from all over attracted by the magical vibe of this place.

In 2016, the same year we released Finibusterre: Latitud 55° Sur, an archaeological campaign was carried out due to the discovery of 19th-century tableware on Playa Donata, on the Atlantic coast of the peninsula. They called me to film the campaign, and that’s how my second documentary, Patrimonio Fueguino: Rescate en Playa Donata, was born.

Martín Vázquez is an archaeologist who has been working in Península Mitre for almost 20 years. Invited to be part of the campaign with his colleague Francisco Zangrando, he took the opportunity to deepen his work on past human occupations. “All the collaborations I have done with these teams related to shipwrecks fascinate me,” Martín explained in the interview we did during the documentary expedition. “Many of the shipwrecks that occurred in this area happened when hunter-gatherers known as Haush lived here,” he says. “These groups of hunters took advantage of many of the shipwrecks’ remains … it is a super interesting case from an archaeological point of view because there are not many like it.”

The cultural value of the Península Mitre is immense and complements the natural diversity found both inland and on the coast. If you have sharp eyes and quick reflexes, you may see a huillín (southern river otter), a friendly carnivore—and an endangered species—of great importance to the ecological balance of its habitat. And the coastal marine environments of the peninsula, such as the dense forests of macroalgae and large expanses of peatlands, are key ecosystems for the health of the Earth.

Above and below the Earth’s surface, the forests of Península Mitre work to sequester carbon and contribute to our home planet’s health. Photo: Rodrigo Manns

The underwater forests of Cabo San Diego, the easternmost point of Península Mitre, are home to algae species that can grow up to 100 feet. Photo: Joel Reyero

That pristine nature was the subject of Hostil, a documentary we filmed between 2018 and 2021 with a group of friends from my production company, El Rompehielos. This documentary, directed by Fernando Urdapilleta, sought to propose solutions to fight climate change. Consulting with glacier specialists, we met Rodolfo Iturraspe, an engineer, hydrologist and scholar who knows the water resources of Tierra del Fuego like few others. That was where we learned about the values of the peatlands. Once again, we set foot on the peninsula.

It turns out that Mitre is Argentina’s most important carbon reservoir due to the enormous presence of this type of wetland, known for its potential to mitigate climate change.

The Ksar in Bahía Valentín, minutes before its crew jumped overboard into this kelp patch. This 50-foot-long vessel was used in an exploratory campaign by a conservation team in Península Mitre. Photo: Joel Reyero

“The benefits, or ecosystem services of peatlands, are very varied. The most recognized, due to its global nature, is the ability to control the carbon cycle and, through the carbon cycle, climate change,” Rodolfo says in Hostil. “There is recognition and there is also concern worldwide because there are many uses of peat that degrade these ecosystems.” Regarding the extractive use of these wetlands, he concludes, “sustainable peat extraction does not exist because the replacement of peat takes millennia.” Rodolfo says that there are 270,000 hectares (over 665,000 acres) of peatlands surveyed in Tierra del Fuego. And almost 90 percent of that is on Península Mitre, a landscape of peatlands and lagoons he describes as looking like another planet.

The mouth of the Bonpland River. Bahía Aguirre, Península Mitre. Photo: Joel Reyero

There is a fair amount of research about the benefits of peat for the health of the planet. What not everyone knows is that the details of its surface often mimic landscapes worthy of a fairy tale. Photo: Rodrigo Manns

Various local artists and creative thinkers used these extraordinary landscapes to inform their work and make the place and people of Tierra del Fuego visible to the world—an important part of the push to protect the peninsula. This includes the work of documentary photographer Luján Agusti, who focuses precisely on the Fuegian peatlands, a visual chronicle that led her to explore Península Mitre—according to her, “one of the great treasures of our planet.” Her internationally renowned project highlights the importance of conserving these environments. She believes that debates about the law have allowed many people in the community to learn more about this place. “It is through knowledge that we can understand the responsibility we have to protect the land where we live,” she says. For Luján, the creation of the protected natural area, “implies a huge action, not only locally and in the present, but for the generations that follow us, here and around the world.”

Conservationist Kris Tompkins also appears in Hostil, where she says she is concerned about how disconnected humans are from nature. “We have our heads in telephones and computers. The idea to go out and explore is really down the list these days. And I think that this is one of the crises that humans face socially and culturally, that people don’t know where they live,” she says. “You can’t love something you don’t know.”

The tide nears its peak as Felipe Cancino returns from exploring Península Mitre from south to north. Photo: Rodrigo Manns

Left: A red octopus clings to seaweed as it seeks out some rest.

Right: The red sea urchin is one of many species that thrives in the kelp forests of Península Mitre. Photos: Joel Reyero

The time I have spent getting to know Península Mitre, and the people I have met here, are a reminder for me that we need to relate more and better to natural environments and be more conscious of their preservation. Although it is hard to believe, the law that protects Península Mitre was passed during a bitter paradox. While the designation of the protected natural area was taking place, a fierce wildfire—sparked by human irresponsibility—caused irreparable loss of biodiversity in our province. Thousands of hectares of native forest disappeared. It was a wake-up call that reminded us how much there is to do to take care of the planet.

The community of Tierra del Fuego decided to preserve its natural treasure, which contributes to the well-being of the planet, and all of us. It was a local community triumph of global significance due to the ecosystem benefits provided by this place, which should be preserved for anyone who wants to immerse themselves in its wild nature. I wonder how many places like this future generations will get to know?

The main characters of a historic triumph. After the approval of the law that created the Península Mitre Natural Protected Area, members of different environmental organizations and representatives of the community immortalize their happiness, which is ultimately for us all. Photo: Joel Reyero