What's a Climbing Road Trip Without a Car?

narinda heng finds out by taking public transit from Oakland to Yosemite National Park.

All photos by m. estrada

I met my friends Endria Richardson and m. estrada bright and early at the Jack London Square Amtrak Station, carrying 165 liters of food and gear in a 100-liter rolling duffel and a 55-liter backpack. I had lugged it all from my home, starting in East Oakland, California, before taking a 40-minute bus ride to Chinatown, then walking for 20 minutes to the train station. With my trad climbing gear, camping equipment and a surplus of Patagonia Provisions® tinned fish, I was glad Amtrak allows each passenger up to two 50-pound bags.

Endria Richardson (left), author narinda heng, and photographer m. estrada’s feet hang out while waiting for YARTS, the public transportation to Yosemite National Park, outside the Merced Amtrak station. California.

I’d conceived of a five-day climbing trip, taking public transit from my doorstep to Yosemite Valley and back, as a kind of challenge. I had learned to climb when I mostly biked and took public transit around Los Angeles, but I couldn’t imagine getting up the steep hills to Malibu Creek or Echo Cliffs without a car, and long-distance road trips were a quintessential climber experience I embraced despite long-held climate concerns. I wanted to break through the cognitive dissonance. It would take more time and effort, but I wondered if ditching the car could be a form of simplification. Sometimes Yosemite feels like Disneyland—crowded, with limited parking and thick traffic, and unpredictable cars, bikes and pedestrians. Without a car to worry about, there’d be no fear of driving past the right pullout and having to go all the way around the loop again, and no anxiety about where to leave a two-ton encumbrance, nor how much gas was used or needed. All I’d have to do is pack my bags and walk in the right direction.

Making good use of Amtrak’s generous luggage allowance.

Of course, there are practical reasons climbers typically opt to drive. Unaccustomed to listening for boarding announcements, we nearly missed the one and only train scheduled that day and hurried on with our luggage near last call. The conductor scolded us for not paying closer attention, as though we were some rascally kids. Being a trio of people of color, we were not surprised to be perceived or treated as younger than we are, particularly by a white-appearing person.

This is why we love cars, isn’t it? Traffic, the cost of gas and the emissions our vehicles generate (and the psychological toll that climate anxiety takes) are often not enough to outweigh the conveniences: being on our own schedules, throwing gear haphazardly into a trunk, no close encounters with delayed buses or surly conductors, and having a mobile closet or even a bedroom that can be locked. There are complicated mental gymnastics involved in so many of our outdoor recreational activities, contradictions between climate consciousness, a desire for convenience and the need for safety from racist, sexist or homophobic micro- or macro-aggressions.

narinda enjoys the space, time and quiet afforded in a train car.

That frantic moment behind us, we got settled on the train and watched Emeryville, Richmond and the coastline go by before the tracks took us eastward toward the Central Valley, hot and smoggy from all the trucks coming and going with food and fertilizer, literal tons of materials on which our economy runs. Three hours passed pleasantly as we meandered to the café car, listened to music, chatted, wrote in our notebooks, gazed out the window—no one preoccupied with safely maneuvering through traffic.

Endria and narinda get their first sight of Yosemite Valley walls from the YARTS shuttle.

After disembarking at Merced station, we loaded up onto the YARTS coach for the final leg of transit. We rode along Highway 140 through rolling golden foothills and then by the Merced River, the road winding around tighter and tighter curves with steeper drop-offs until finally tucking into Yosemite Valley. The two-and-a-half hour trip gave me time to enjoy being among the mix of tourists and locals on YARTS. Some people had overstuffed duffels and backpacks like we did. Others loaded their bikes into the spacious undercarriage and had just a lunch bag. A pair of middle-aged men boarded at one of the hotel stops, and I saw one rest his head on the other’s shoulder; a display of intimacy that was sweet to see, to have the time to notice.

The ranger at Camp 4 seemed surprised that the crew had no need of a parking permit.

We finally arrived at Camp 4 about six hours after leaving Oakland. As we set about making our home for the next few days in the late afternoon sun, I tried to imagine what it would have been like to arrive in the ’70s, alone and seeking climbing partners like the stories romanticized in climbing media. But during the “Golden Age” of Yosemite climbing, Southeast Asia was being loaded with landmines by the US military. My present queer, Khmer American self could hardly have existed then, let alone find her way to Yosemite, or to climbing at all. I pushed the fantasy away and reminded myself: I am here now, and I can experience this place in my own way.

Yosemite Falls in full force.

Because we could only go as far as we had the time and energy to go on foot, the Valley felt both bigger and smaller at once. We stuck to single-pitch climbs and a few of the classics; when we wanted to walk less, Swan Slab was a five-minute stroll from our tents. We weren’t looking to test ourselves or perform any feats of fitness or strength, but to see whether we could feel a deeper intimacy, a closer connection to this place.

Endria’s first trad lead at Swan Slab, less than five minutes from their campsite.

As we came to know certain trails better, we were dumbfounded by how much more there was to know, from the cliffs to creeks. I felt more there without the easy escape hatch of a car. More awe and gratitude. On one of our long walks on Valley Loop Trail, we came across a small, bright red Croc drifting at the bank of the slow-moving Merced. I found a stick and fished it out. I wouldn’t have seen it, and it would have been harder to stop and do that, from a car. I thought about the many places I have only ever driven to or through, the places I paid little attention to on my way to somewhere else. Is loving the things I experience in a place the same as loving that place?

Food storage boxes in the Valley are bear-proof but still susceptible to shenanigans.

We marveled at the town-ness of Yosemite Valley as we walked northeast for a day of cragging at Church Bowl. What had it been like before all these buildings, when there was no Ahwahnee hotel, and when Ahwaneechee and Miwok and Mono and Paiute and peoples whose names have been erased made their homes in this valley? Their descendants still fight for lifeways and agency to steward these lands. I wondered how Yosemite could have been developed differently through cooperation rather than genocide, and what possibilities lay ahead as more of us recognize the need to repair the wrongs.

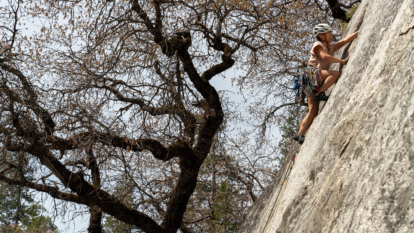

narinda leads La Cosita – Left in shirtsleeves, not much different from Yvon Chouinard’s classic rugby shirt.

The author uses Endria’s Nano-Air® Jacket as a gear tarp at Church Bowl.

On our last day, we packed up, said goodbye to Camp 4 and reversed our trip. YARTS was quiet at that early hour, but the Amtrak train was crowded, surprising us. It made sense though: It was a Friday, and we were hopping on the train near the end of the route rather than at the beginning. We found seats wherever we could. The man I sat next to, plaid shirt tucked into denim jeans, said he’d been riding since Bakersfield and would go on to Sacramento. He dove back into his Western novel before I could ask what brought him on such a long commute through the San Joaquin Valley. Agricultural work? Oil fields? Just visiting?

From Oakland’s AC Transit to Amtrak to YARTS and back, I spent five more hours traveling than I would have if I had taken a car to Yosemite Valley, assuming no traffic delays nor a huge line at the entrance. Our three roundtrip tickets cost about $210 total. If we use the IRS’s standard mileage rate, the 312-mile round trip in a car would cost about $204. According to the EPA, a typical car emits approximately 400 grams of CO2 per mile, so we saved nearly 125 kilograms of carbon emissions. A small start. There are things worth saving more than money.

The journey with Endria and m. helped me relinquish a little of my romance with the road trip. I feel closer to Yosemite Valley and to the places in between. I love climbing for the tactile sensations of connection between my hands and the rock, between myself and my climbing partners. I love riding transit for similar reasons: to share space and time with people, to see and be seen. I want more climbing trips at the slower pace of feet, bicycles, public transit, collective cooperation.

Climbers make a game of choosing to take the more difficult path. As I write this, I know that my dusty Subaru will still be spotted at trailheads and crowded parking lots around California, Nevada and Utah for years to come. But you might also see me slowly dragging a big duffel full of climbing gear away from a bus station.