Trust The Scientists

Why we rely on lab tests and data more than ever to make decisions about our products.

There are 20 machines in the Patagonia fabric lab in Ventura, California. Each has its purpose, but they all serve the same goal: to investigate how materials perform and why and how we can make them better. There are devices that test how well a material repels water, others that measure the pilling and shedding rates of fabric, and there’s another machine that pulls air through fabrics to test breathability. Many of these machines have nicknames, like Pascal, the UPF (think sun protection) testing machine that earned its name from its resemblance to the eponymous chameleon from the movie Tangled.

The entrance to the lab has a heavy door equipped with a downward-facing fan called an air curtain that keeps the temperature stable at 70° F with 65 percent relative humidity. Through the door and across from Pascal, Katie Johnson, a material performance engineer, is cutting a piece of fabric into four rectangles, which will each be placed inside a stainless steel canister the size of a water bottle. Along with the fabric, Katie adds a few BB-sized stainless steel balls to the canisters before dropping each into separate slots in a centrifugal washing machine, then she sets the washing cycle for 40 minutes. As the machine whirs, the steel balls hit against the fabric to mimic abrasion, creating a dissonant symphony of swooshing water and what sounds like a bunch of miniature steel drums playing. This method is commonly used to test colorfastness (how well a material resists fading), but Katie is testing the different shedding rates of fibers for a wool and polyester fabric blend. At the end of the washing cycle, she’ll measure the amount of fibers that came off each piece of fabric, then repeat the test until she has enough data to confidently compare this particular fabric to others.

Our Forge R&D team is nuts about bolts. Photo: Kyle Sparks

Katie is one of more than 20 scientists and engineers at Patagonia who are using data to develop, test and improve the materials and technologies we use to make our products. We rely on science to find the best-performing fabrics for our technical gear and also to inform our efforts to reduce our ecological footprint. We’re using data not only to clean up our act but also to find solutions that can improve the global clothing industry, which contributes up to 10 percent of the global carbon impacts driving the climate crisis. We’ve set an ambitious but attainable goal to reach carbon neutrality across our entire business by 2025. That includes our supply chain, which presently accounts for 97 percent of our carbon emissions and mostly comes from the raw materials we use. This means that our material scientists are at the forefront of getting us to carbon neutrality and beyond. This effort starts, like all matters in life, with chemistry.

“There is this term in chemistry called regrettable substitution,” says Elissa Foster, a member of Patagonia’s materials R&D team. “It’s this idea that sometimes a chemical is identified as being harmful to the environment or toxic to humans, and it gets banned, and then something else starts to be used instead.” If the new chemical isn’t subject to rigorous testing to ensure that it will be less harmful than the original one, we run into problems—like when manufacturers replaced the bisphenol A (BPA) used in receipts or plastic bottles with bisphenol F or S, which studies show may have the same negative impacts on the human body. “That would be considered a regrettable substitution,” says Elissa. “And that is what we don’t want to happen at Patagonia.”

To help us avoid such regrets, Elissa and other scientists on staff start by gathering data about what happens over the life span of a product. This means measuring the carbon and water footprint of each material and the environmental damage left behind by the manufacturing process—information that helps us understand where we need to improve and which materials have what impacts on people and the planet. If a material’s largest footprint results from the weaving process, we know we need to look at what type of energy is being used at the factory where the weaving takes place. If the factory is running on fossil fuels, we know we need to talk with our supplier about switching to renewable energy.

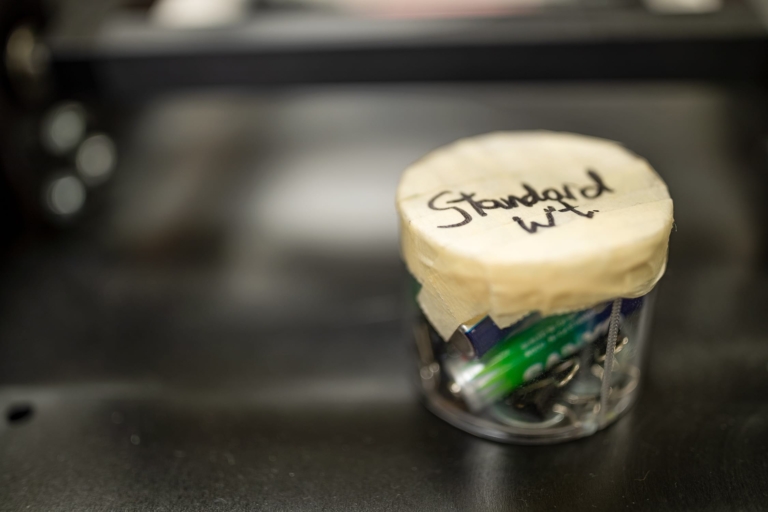

To measure the loft of fabrics and insulation, our scientists created a standard weight using objects from the junk drawer. Photo: Tim Davis

There’s a lot of weighing choices and number crunching involved. For example, take Patagonia’s Woolyester fleece fabric, which is created by spinning postconsumer recycled wool yarn with a featherlight micropolyester. When our recycled wool suppliers in Italy brought us this fabric, Elissa’s team compared its carbon footprint to that of virgin polyester fleece, recycled polyester fleece, and a cotton and wool fleece blend. “Hands down, Woolyester was a win,” Elissa says. In general, the recycled natural fibers we use have a much lighter footprint because we’re eliminating the process of growing the fiber, which often has the biggest impact.

While the environmental scientists at Patagonia are gathering impact data and advising product designers on what materials can help minimize the carbon footprint of a particular product, the material scientists are running tests, such as the one Katie and her team led, to validate the quality of a fabric and ensure that it actually functions the way we expect it to. Then there’s the material innovation team that works on the fabrics of the future, researching the best possible evolution for all the materials that go into making Patagonia clothes.

This kind of research takes time and the ability to look at one thing and imagine it as something slightly different, like the high-density polyethylene (HDPE) made from recycled fishing nets in our hat brims, a material that was five years in the making. In 2013, Bureo, a small California-based company, started making skateboard decks and sunglasses frames from fishing nets salvaged from the coast of Chile. A year later, Tin Shed Ventures, Patagonia’s venture capital fund, offered Bureo financial backing to explore how to create material for the clothing industry from those nets. “We saw something much bigger and they did, too,” says Rob Naughter of Patagonia’s material innovation team.

If they succeed in turning their material into yarn that can be woven into textiles, they will have a product that can be used in the apparel market. But making things from trash is not easy. You have to determine the best ways to clean the discarded fishing nets, the best way to recycle the material and then how to turn it into a new product. “It’s up to the materials team to justify what materials we are buying into,” Rob says. “How much waste can this potentially save from polluting our oceans? What is the carbon footprint in doing that?” That’s where the facts come in.

To simulate the abrasion and other abuses a garment is sure to face, we run prototype fabrics through a 40-minute wash cycle with BB-sized stainless steel balls. It’s loud, but impossible to cheat. Photo: Tim Davis

Elissa’s team has published findings about microfiber pollution in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, so other scientists may learn from and build on their work. And our environmental grants program is providing funding for the San Francisco Estuary Institute’s plastic pollution research, so we can understand more about how plastic behaves in the marine environment.

Science alone can’t solve the drawbacks of different materials, but it makes the journey toward sustainability clearer. We know we can stand behind our transition to recycled materials because data gathered through life cycle assessments shows that using recycled fibers can reduce carbon emissions by 44 to 80 percent, depending on the fiber. There will always be trade-offs. For any given material, our scientists and designers need to find the best balance that does the most good.

We recognize that every product we make comes at a cost to the planet. We take this responsibility seriously—because we want to leave our kids a world full of beauty and wonder where they cannot just survive, but thrive. Years from now, we want to look back and not have any regrets that we could have done more or done better. Science keeps us true to the task.