The De-fence of Patagonia: An Employee’s Internship with Conservacion Patagonia

Patagonia’s environmental commitment extends to its extensive support of the Conservacion Patagonica program. Each year, employees have the opportunity to participate in one of three separate service trips designed to tackle the mountainous work required to transform retired ranches into a stunning new national park. This report comes to us from recent trip participant Andy Mitchell, of Patagonia’s Dealer Services Dept.

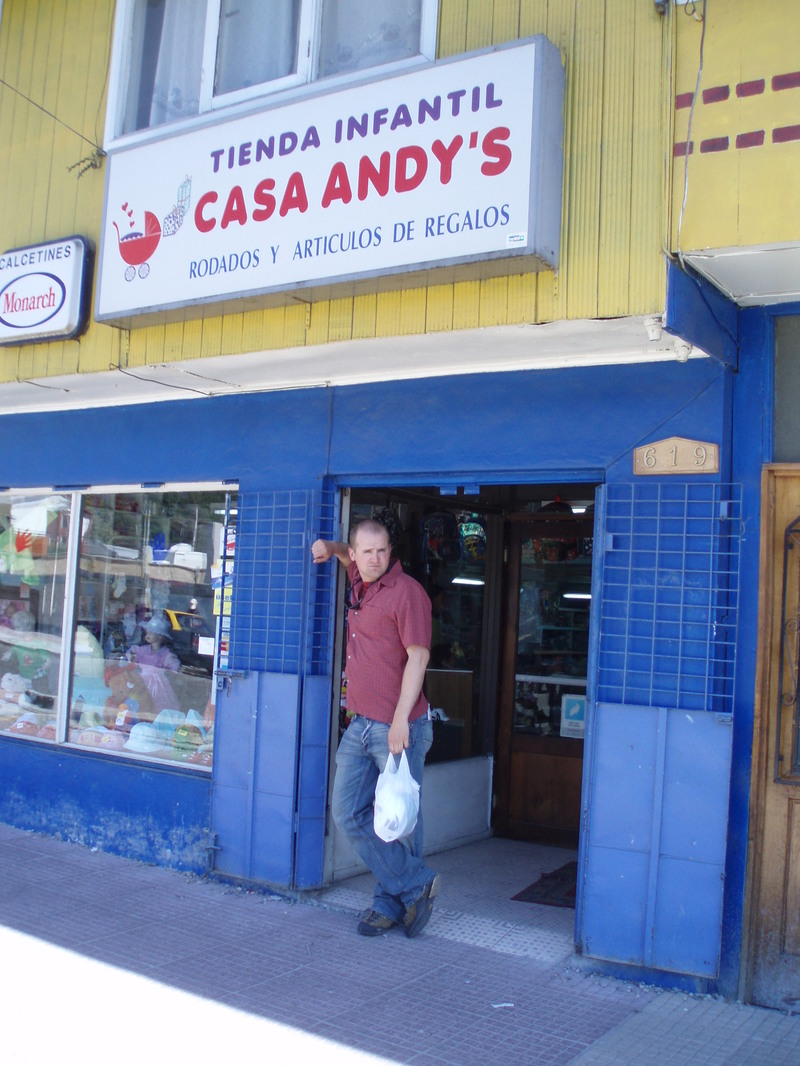

Andy Mitchell of Patagonia’s Dealer Services Dept. finds that he already has a home in the heart of Patagonia. Photo: Suzy Reinhart

We left Ventura at 8 am Sunday morning, and arrived some 32 sleepless hours later at the Estancia Valle Chacabuco, region XI, Aysen, Chile. The trip is over 7000 miles, and we ultimately settled farther south on the planet than South Africa and even New Zealand; farther east than the entire United States. Completely zonked, we met the expectant Doug and Kris Tompkins, philanthropist founders of Conservacion Patagonica. Malinda Chouinard also greeted us on behalf of Patagonia Inc., and her curiously missing husband Yvon (who would reappear the next morning, having slept the night in his waders, in his car, in a ditch). The opportunity to meet these people was tremendous, and only overshadowed by the fruits of their efforts.

Daisy—an Estancia employee—out standing in her field of fence removal. Photo: Andy Mitchell

We toured the Estancia the next day, packed into the 4-wheel drive “Delica” mini van. Pressed against the glass, we saw great herds of mythic guanaco. A relative of the llama and camel, it is built elegantly but odd, and shares the coloring of an African gazelle, complete with white swath across the body. We saw Andean condors soaring with white collars and ten-foot wingspans, their size impossible to comprehend. We saw Patagonian fox, with solid stocky legs and a ball shaped head, smaller and more stout than the North American version. The Estancia is enormous and reaches from the surreal blue waters of the Rio Baker all the way the Argentine border, comparable in size to the city of Chicago, only larger. It took us hours just to drive the main road, always watching fences going on and on to infinity.

That is where we spent the majority of the next 3 weeks, with views of Andean glaciers and ice fields. I expected we would spend some time pulling fence, but did not expect to be fully entrusted with long tracts for days at a time. We spent hours pulling and coiling wires, pulling pickets and posts, moving and piling everything. We got dirt under our fingernails, in our ears, in our hair, and down our backs. We got sunburned, bug bitten, and covered in burrs. We thrived on Nescafe, mutton, and cheese sandwiches. We drank mate, vino, pisco and cervezas. Nights were filled with laughter and aching groans.

Lago Jenimenie, Jenimenie Preserve, north of Valle Chacabuco. Photo: Andy Mitchell

We toured the neighboring wildlife preserves to the north and south and saw the pride many Chilenos take in them and the ill treatment these sanctuaries receive from others. We were able to experience the scale of the project and get a sense for the time frame at hand. Doug Tompkins points out it will take the land at least 150 years to recover from the effects of a century of overgrazing. The enormity of the timescale is decidedly humbling. Similarly, the scale of the fence removal alone is more than one lifetime. It is a lesson in mortality and team-work. Problems like this will never be solved by individuals, only by continuous efforts from groups dedicated to a similar vision who are able to convince and recruit others that it is worth pursuing. I see that as one of the many reasons Patagonia Inc. has made our company’s participation a priority. I am proud that if all goes well, nearly 10% of employees will have visited and worked there by the end of next summer.

Team Conservation Patagonica, February ‘07. Photo: Andy Mitchell

I am forever grateful to Patagonia for giving me the opportunity to see the place we take our name from, and to play a small part in protecting it. I am grateful to the group I went with, we were diverse in personality and strengths, and showed great patience and support for each other. I am grateful to my coworkers who split my job nine ways in my absence and sealed up every loose end they could. Most of all, I am thankful for the good work being done in Patagonia by the people changing the Estancia from a trodden sheep farm into the wild place it so wants to be.