Kitty Calhoun’s Trip Continues

As my friends and I get older, the threat of slipping into a normal lifestyle becomes more real. I have to mow the lawn, get the oil and filter changed in the car, go to the dentist. These days, given a choice, I would rather do a few sport pitches and get a good workout in, than burn a whole day on a multi-pitch route. My sense of adventure, along with my confidence, is fading with my youth. Yvon Chouinard once said, “When everything goes wrong, that’s when adventure starts.”

Did I really want to go through an adventure, including all the accompanying fear, unknowns and discomfort that are usually associated with it? On the other hand, I was perfectly healthy with no good reason not to test myself again. I decided Tangerine Trip, a short but steep, moderate aid route on El Cap, would be the perfect experience to get me off the slippery slope to complacency.

Karen Bockel and I had tried to climb the Trip already last fall, but had to retreat off the fourth pitch because her recently surgically repaired knee screamed in protest. Now, as we drove into the Valley again, a huge stubborn low pressure system conspired against us. But the Trip is so steep, we wouldn’t even get wet. As is often the case, committing is the hardest step. So we enlisted emotional and logistical support from a friend, Yoshiko Miyazaki-Back. She helped us fix and haul to the top of our previous high point, then she rappelled down, tied on the haul bags and kept them out of the trees.

Yoshiko at the belay, top of pitch 3. Photo: Kitty Calhoun

Karen and I were in motion now—not thinking, just doing—like robots. I sorted the rack; she re-stacked the ropes. She put me on belay and I started up the crux pitch. Eighty feet up was a series of old mangled iron and broken copperheads. I tested a head, moved off it onto the next head and in a split second I was falling head-first.

“Catch me, Karen!” I screamed. After fifteen or twenty feet, I came to a stop. After an explosive sit-up, I was able to get upright. I couldn’t allow fear to enter my mind. Retreat would be more than difficult. Adrenaline surging, I started pulling myself back to the last piece of protection. I desperately wanted to complete the sixth pitch before dark. Just as the sun set, I reached the anchors.

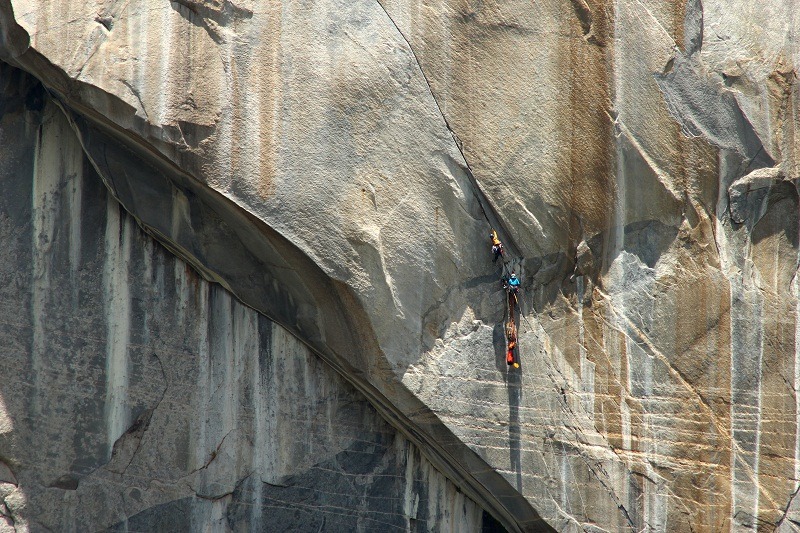

Kitty leading the second half of the crux pitch. Photo: Tom Evans

I was exhausted and needed to pee. As I hastily attempted to hang the fifteen-pound rack on the anchor, I dropped all our hooks, which are critical in aid climbing. With a single “cling,” they sailed through the air hitting ground hundreds of feet below. Disaster. When Karen finished cleaning the pitch and arrived at the belay, I said in a defeated voice, “I dropped the hooks.”

Karen, a German physics grad who came to the U.S. on a track scholarship, had little wall experience. Even so, as soon as she heard the sound, she knew the consequences. She patted me on the back and said in her sing-song voice, “You got us up the crux of the route. Let’s set up the porta-ledge now. We’ll be okay.” I chose to take her word for it and do what she said. Apparently she had already learned in her life to accept, without surrender.

Kitty enjoying time in the porta-ledge. Photo: Karen Bockel

After a fitful sleep, I embarked on the next lead, filled with apprehension. There were several hooking sections and I was hoping I could use my nut tool or one of my bird beaks. Since a hook has much greater contact with the rock than a beak, I was going to have to be very smooth when I transferred my weight from beak to beak. I was out of sight, and Karen could hardly hear me, when I asked for slack and slowly moved onto my first beak. “Trust and commit,” I began muttering faster and faster. The beaks never wavered and I made it to the anchors. We were going to make it to the top of El Cap. Karen knew this too as soon as she saw the gleam in my eyes.

Karen cleaning a buttonhead pitch. Photo: Kitty Calhoun

We only climbed three pitches a day, and a couple of those pitches took me four hours to lead. I couldn’t reach the spaced-out buttonheads so I had to tape a rivet hanger onto a stiff draw onto my nut tool. The wobbly extender with bits of tape hanging off it looked like something out of a Dr. Seuss book. (Oh, the wobbly extender you’ll trust your life to …) I was so stressed that I neglected to hydrate properly. My resurfaced hips began squeaking audibly.

Kitty with the wobbly extender. Photo: Karen Bockel

After five days on the route, I finally broke down. Using the extender had become tedious and now I was looking at more hooking with beaks. A soloist had caught up with Karen and I could hear them laughing. I was exhausted and could no longer delight in the problem-solving process. Tears rolled down my face as I yelled to Karen’s friend, “Do you want to pass us? You could drop us a rope too!”

Still laughing, the guy replied, “No, go ahead. I’ll loan you my hooks.”

The offer of hooks at that moment was my saving grace. I wiped the tears away and recommitted. It was such a relief to be moving off something more stable than a beak. In fact, hooks, which once felt sketchy to me, were like anchors now. Had I never dropped them in the first place, I would probably still be afraid of weighting them. I would not be as skilled an aid climber, nor as confident. Perhaps it is true: that which doesn’t kill you makes you stronger—otherwise known as post-traumatic growth.

Karen and Kitty on top of El Cap. Photo: Karen Bockel

A few hours later, Karen and I reached the summit, and I am still basking in the afterglow of success. Though I’m back to staining the deck and doing laundry, I appreciate the mundane all the more. But contentment has a time limit. After a while, not even a mountain of chores can stand in the way of my need for another adventure.