The Quest to Save 100 Waves in Peru

Listen to the story

Carolina Butrich loves to read and hates mangoes. She uses Microsoft Excel for everything, including designing her house. She gives abundant affection but is claustrophobic and can’t handle hugs. Above all, Carolina is a flame that does not go out.

Although we went to the same school in Lima, Peru, we never met there. The first time I saw her was in the waters of the Cañete River in 2010. She showed up with her long hair dancing in the wind and tan smile lines, the kind that indicate a life spent near the sea. I was suffering to keep my kayak upright while she paddled for two hours straight with ease. We didn’t talk, and I didn’t ask her name. Years later we realized that was the first of many sessions together as our friendship built around protecting surf breaks and nature in our homeland bloomed—a task for which I could not have asked for a more ideal partner.

Carolina Butrich at home in Peru. Photo: Cristina Baussan

Peru is generally known for Machu Picchu, mysterious Nazca lines and its flavorful ceviches. What most don’t know is that the first law to create a legal system of protecting waves was born here. In the ’80s, the mayor of the Chorrillos district started the process to build a road that many say changed the ocean’s landscape dynamics and destroyed the now mythical La Herradura . Years later, when a poorly planned pier almost destroyed the perfect wave of Cabo Blanco, the surfers organized themselves. They formed a conservation association and left no stone unturned until the Peruvian Congress approved the Ley de Rompientes (Law of the Breakers) in 2000. It took 13 years for it to go into effect and became the legacy of a new generation of Peruvian surfers committed to saving waves. In 2016, Chicama, famous for being the world’s longest wave, was the first to be protected. Today, there are 43 protected waves in Peru thanks to thousands of people who’ve joined the Hazla por tu Ola campaign, an effort that fueled the surf community with purpose and welded my ironclad friendship with Carolina.

After we first met at the Cañete, I started a project called Conservamos por Naturaleza, an initiative of the Peruvian Society of Environmental Law that invites and facilitates anyone’s involvement in nature conservation. We promote a voluntary conservation movement because we believe that conservation must be ingrained in the culture of everyday society. Today, we have over 250 initiatives supported by families, communities and organizations that protect almost 500,000 acres of natural ecosystems in Peru.

Carolina and Bruno Monteferri enjoy a morning session at Los Órganos, a wave that they helped protect in Peru. Photo: Cristina Baussan

While I dedicated myself to Conservamos por Naturaleza, Carolina traveled the world, with water being the sole constant in her life. She competed in windsurfing racing until she saw a video of legendary windsurfer André Paskowski riding waves at Ho‘okipa in Maui. She decided that within a year she would be riding those same waves. So, she started taking the bus nearly 400 miles (640 kilometers) north from Lima to Pacasmayo every weekend to learn how to ride waves while pursuing a degree in environmental engineering.

Carolina takes flight at Zarate Beach, Peru. Photo: Walter Wust

Soon, windsurfing Ho‘okipa became a reality, and just two years later she was competing against the best in the Professional Windsurfers Association world tour. Maui in Hawai‘i, Paracas and Pacasmayo in Peru, and Jericoacoara in Brazil became usual stops. At each location, Carolina found an extended family. Before finishing her degree, she got offered her dream job in Jericoacoara as the head windsurfing instructor at ClubVentos. Carolina didn’t want to miss the opportunity, though she did sign a contract with her mother, who helped her finance her studies, promising that she would return six months later to finish college.

That decision would alter the path of her life because in Brazil she met André Paskowski and they fell in love. André had a terminal illness, and they would only get a year together. But they were determined to make memories. Between therapies, they traveled to film the windsurfing documentary Below the Surface, which focuses on former Professional Windsurfers Association World Champion Victor Fernandez and his friends. André passed before finishing the documentary, but Carolina completed it. The process helped her get on her feet again. They had the goal of presenting it at a film festival in Sylt, Germany, and she knew that’s what André would have wanted. “We had everything to be happy together: love, trust, fun, common interests, respect, admiration, everything … except time,” Carolina wrote in a farewell letter.

We saw each other in 2013 at an environmental event, and I told her about Conservamos por Naturaleza. When she came back to Peru two years later, she visited our office and said that she had returned to, “give something back to the sea for everything it has given me.”

The author holds baby Aulia before heading back for a few more waves. Photo: Cristina Baussan

I told her that our organization was created precisely for people who wanted to generate a positive impact, and that her timing was spot-on since we were about to launch a campaign that would allow us to protect the waves of Peru. When I mentioned that we had no budget and needed to raise over $500,000 in the next 10 years while uniting a very dispersed Peruvian surfing community to protect 100 waves, Carolina asked, “When do we start?”

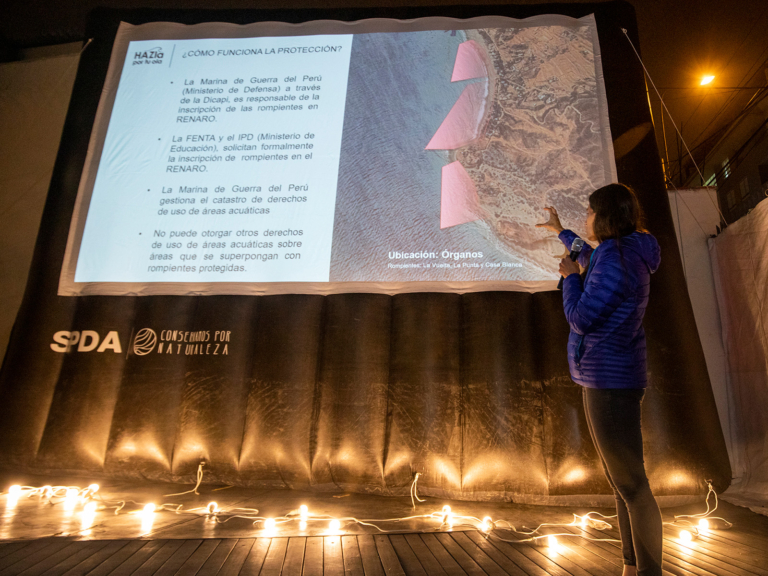

A few weeks later, we found ourselves in front of a crowded room to launch Hazla por tu Ola. Carolina, terrified of speaking in public, stuttered due to nerves but against all odds—and encouraged by a couple of pisco shots—explained that if we wanted to protect our waves, we had to be organized as a community and not rely on the government. Today, Carolina handles herself with ease when she gets on stage. A key part of our organization is to inspire citizens and private companies to take action for nature conservation. Her dedication and leadership toward this goal earned her the Carlos Ponce del Prado Award in 2019, and the Latin America Green Award for Hazla por tu Ola in 2020.

Protecting your wave is as simple as a three-step process and as complicated as getting it passed through the Ley de Rompientes . Photos: Cristina Baussan

There are a few different approaches when it comes to protecting surf breaks. In countries with strong institutions and more mature ocean governance structures, surf-break protection usually falls under marine spatial planning regimes. These processes allow governmental agencies to navigate the different interests over a particular marine area and set the rules for its use. For instance, countries such as New Zealand and Australia have coastal management plans, where recreational uses are prioritized in wave zones and activities that may affect those zones are limited. In Australia, there’s even a surf management plan for the Gold Coast and millions of Aussie dollars are invested for its implementation.

But in many other countries, marine spatial planning is nonexistent and the communities that are committed to protecting marine ecosystems are in constant dispute with other stakeholders to make conservation a public priority. This is the case in Peru, where, for example, the Navy receives several requests to grant permits for the construction of ports, pipelines, piers, coastal defense structures and more.

Carolina and Bruno’s partnership has proven to be successful. There are 43 protected waves in Peru today, thanks to the work of Hazla por tu Ola and its extensive network of collaborators. Negritos, Peru. Photo: Cristina Baussan

The Law for the Protection of Surf Breaks created a formal process for citizens to put conservation before other potential uses. The way it works is if you can prove there’s a wave in a potential area of protection, you must submit a technical file and a map of the area to the Peruvian Navy. These documents need to show the existence of a wave and its physical features through a seabed analysis and a swell record. The Peruvian Navy then validates the information, and once the wave is registered in the National Registry of Surf Breaks, the government can no longer grant rights for activities that may affect the waves—meaning no new breakwaters, docks, piers, underwater pipelines and more. Basically, all construction that could affect the window and path of a wave are avoided.

With swells coming in from the north, west and southwest, Máncora is a wave and tourist magnet. This is one of the surf breaks that Hazla por tu Ola helped protect. Talara Province, Peru. Photo: Cristina Baussan

Led by Carolina, Hazla por tu Ola identifies and works with community leaders to raise the funds needed to hire specialists. The specialists then prepare the files and follow up with the authorities so that the waves are registered and stay protected. It costs $3,000 to $6,000 USD to get the research done and submitted to the Navy for every single wave. To date, citizens in Peru have raised 90 percent of all funds needed for wave protection.

In 2018, we were invited to the Global Wave Conference organized by Save the Waves Coalition (SWC) in Santa Cruz, California. SWC played a key role supporting the local Peruvian community in the process to protect the iconic wave at Huanchaco, famous for its traditional caballitos de totora, an individual fishing boat woven out of reeds and used by the locals to fish for the past 3,000 years. The relationship with SWC has grown throughout the years and has been key in amplifying Hazla por tu Ola’s model in other countries, connecting us with activists across the world. Our most recent collaboration with them consists of an online platform with a systematization and comparison of legal tools and approaches for the protection of surf breaks, including case studies from 12 countries. We hope this information will help local leaders and politicians to commit to protect surf breaks all over the globe.

Carolina takes the mic and inspires a crowd of future wave protectors. Photo: Conservamos por Naturaleza

With momentum on our side, we’re determined to save as many waves as we can. “We have set the goal of having 100 waves protected by 2030,” said Carolina. “We are not going to stop until we have all the waves in Peru protected by law and there are more countries that apply this model.”

And it’s working. The Peruvian model is being adopted in Latin America. Caro has been working with grassroots activists in Ecuador who created a new collective called Mareas Vivas, which is ready to start a campaign to collect citizen signatures and present a law proposal to the Parliament for surf breaks protection. South of the border, in Chile, after a speech I gave about Hazla por tu Ola in 2016, Luis Felipe Rodríguez Besa—now also a close friend—got inspired and co-founded Fundación Rompientes along with the talented filmmaker Rodrigo Farias Moreno and lawyer Juan Esteban Buttazzoni. Fundación Rompientes has played a key role aligning the efforts of several groups for the protection of surf breaks in Chile, and we have been a natural ally since day one.

Recently, the Chilean Congress approved a bill promoted by Fundación Rompientes that seeks to protect Chilean surf breaks. The project is now to be evaluated by the Senate. Also, in Mexico, the community of Puerto Escondido has organized and set up a holistic plan for the sustainable development of their coastal area that includes fostering the creation of a local Ley de Rompientes. Both Save the Waves Coalition and Hazla por tu Ola are providing guidance in the process. When facing environmental challenges, it is easy to feel overwhelmed, so knowing that you can exchange ideas and relate to fellow activists doing the same in other countries is invaluable.

Carolina with her partner Walter Wust and their son Kai at the Illescas National Reserve. Caro helps protect this pristine coastal sanctuary in northern Peru. Photo: Carolina Butrich

When Carolina returned to Peru in 2015, she thought it would be just for a few months. Lima had been a place from which she always found herself escaping. Eight years later, she’s still here because she has found balance. She has a job with purpose, is at the forefront of Hazla por tu Ola’s goal of protecting surf breaks and is surrounded by people who inspire her. She’s also allowed herself to fall in love again and is starting a family. Although she doesn’t try to, Carolina teaches us that living your life without taking anything for granted and setting down some roots—without necessarily anchoring yourself to one place—is key to achieving important changes because, as waves have shown us, there is no barrier that can resist what is done with love and perseverance.

Interested in more activism stories?

Don’t miss the latest environmental stories, action alerts and other ways you can help save our home planet. Join us at Patagonia Action Works today.