The Books in the Patagonia Team’s Bags

If your idea of a great summer read is, like a day in the waves, a little escape from it all, this post may not be right for you. Maybe there’s just no escaping the severity of the climate crisis, or maybe we’re just so glad to have time to sit still with any book at all and reflect on our fate—whatever the reasons, the writer-editors on staff here at Patagonia seem drawn more to exposés and dirty realism than pulp fiction. Not all, though, and the good news is that even the doombats amongst us found in these books—some old, some new—unforced reasons to smile.

The Reality Bubble: Blind Spots, Hidden Truths, and the Dangerous Illusions that Shape Our World by Ziya Tong

There have been times in my life when I questioned if the reality around me was indeed real. Some of these moments involved mind-altering substances, but most recently it was science journalist Ziya Tong who had me questioning everything we take for granted.

We humans have many blind spots. Our senses trick us into thinking that what we perceive is the only true reality, and so we disregard, for example, the perspective of other living beings. “We don’t know what it’s like to be a cow or a chicken or a bat, but it’s like something,” Tong writes. While we’ll never see the Earth’s magnetic fields or ultraviolet rays with our naked eyes (which perceive a mere 0.0035 percent of the electromagnetic spectrum), but learning that there are animals who can see these was humbling—and inspiring. What we see is only a piece of the puzzle.

The Reality Bubble is scattered with insightful and entertaining science stories, from how we use men’s underwear to test soil health to the absurdity of measuring the loss of our rainforests in football fields. The examples Tong uses of how much waste we create and where it all ends up made me uncomfortable; that discomfort, strangely enough, didn’t leave me bummed out. By showing me my blind spots, Tong inspired me to look beyond what is right in front of me and to be inquisitive and open to possibilities. “Our journey must begin right where we are,” Tong writes, “by seeing the ordinary, everyday world we live in, in an extraordinary new way.” —Madalina Preda

Losing Earth: A Recent History by Nathanial Rich

Lately, I’ve been obsessed with the year 1988. The year I was born, was also the year that Yellowstone burned, and the year that NASA scientist Dr. James Hansen testified before Congress, telling the world that global warming was happening, and humans were responsible for it. In the past 30 years, the issue of climate change has splintered along political, religious, and socio-economic lines, and as the list of natural disasters and extinct species grows long it’s dismaying to think it was all avoidable. Because it was, if it hadn’t been for a few key people and events (Exxon Mobil, the election of Reagan, John Sununu etc.) As Nathaniel Rich writes in the introduction to Losing Earth: “Nearly everything we understand about global warming was understood in 1979. It was, if anything, better understood.”

Losing Earth was first published in a special edition of the New York Times Magazine, which devoted an entire issue to missed opportunities between 1979 and 1989. The book version expands on Rich’s article with a larger cast of characters, and scary statistics. Ex: by 2050, the number of people displaced by climate change will be equal to the entire population of humanity during the Industrial Revolution. As a result, it’s both more illuminating and more devastating than the article. Ultimately Rich brings the story back around to us—flawed humans who can’t seem to solve a problem to literally save our lives.

The story has villains and heroes, political maneuvering, crisis, moments of hope. And it was interesting reading it while also listening to the podcast Drilled, which deals with the same time period but with a much greater focus on documents and lawsuits. (Drilled producer Amy Westervelt criticizes Rich for being too gullible). This might be true, but I still found the book valuable. It’s readable, without the ostrich-with-its-head-in-the-sand inducing feeling that some climate reporting seems to engender. It’s extremely interesting how he’s threaded the various pieces together. Most of all, Losing Earth reminds us that predictions made in the 80s have mostly all come true, sometimes more quickly than anticipated. Recent climate reports are not prescient; they’re happening. We blew our first chance to fix what we knew was coming. We can’t afford not to do something about what’s happening now. —Meaghen Brown

Horizon by Barry Lopez

A few chapters into his new book, Barry Lopez recalls a meeting with Dennis Puleston, a young seafarer who sailed to the Galápagos Islands in the 1930s.

“In his eighties when he spoke to me,” Lopez writes, “he struggled to translate his experience, speaking of it as if trying to reach me from another world, a world without GPS, without onboard radar to penetrate darkness and fogbanks, a person guided solely by his magnetic compass, his charts, by a feeling for the wind and the sea, and the look of a windward horizon. The Galápagos he knew, I understood him to say, is no longer there.”

Horizon is a memoir of sorts, as Lopez begins with his California boyhood before setting out for decades of remote and wide-ranging travel—included in the book’s destinations are the Oregon coast, the Nunavut tundra, African rift valleys and the rivers of Antarctica. (Yes, they exist.) The focus is less on himself, though, and more on the places he visits and the changes they’re experiencing in our disorderly time.

Through it all, he keeps the metaphor of navigation at the fore, seeking a steadier course into an uncertain future. He’s aware, as Puleston was, that the places he writes of are no longer what they were. But unlike most memoirs, Horizon looks forward as much as back. What if, Lopez wonders, we weren’t so “distracted by the hope of returning to a world that has already come and gone?” —Malcolm Johnson

Falter by Bill McKibben

Falter is Bill McKibben’s eighteenth book and easily his most frightening. His first book, The End of Nature (1989), was the first to alert the general public to global warming. This one continues the story about how exactly we are destroying our home planet, but it’s more about “the human game,” as he calls it; how we are locked in an economic system in the United States that rewards short-term gain, blinding us to long-term devastation.

In Falter, McKibben names the enemies of our future: the fossil fuel companies, plus the individualist followers of Ayn Rand (which includes President Trump and many of his richest supporters), but also the tech barons. The tech giants don’t care about the planet any more than big oil, McKibben argues, because what they do care about most is speed, AI and super-human powers. They can just replace Earth with Mars—whatever.

Both oil executives and tech leaders are followers of death, as Jonathan Schell wrote in his conclusion to The Fate of the Earth:

Two paths lie before us: one leads to death, the other to life.

If we choose the first path, we in effect become the allies of death and in everything we do, our attachment to life will weaken… and we will sink into stupefaction as though we were gradually weaning ourselves from life, in preparation for the end.

Some tech billionaires even feed projects that will make them live forever which, ironically, leads them further into death. “A world without death is a world without time,” McKibben writes, “and that in turn is a world without meaning, at least human meaning.”

The founder of 350.org, McKibben reminds us about the power of protest, civil disobedience and the need to change the economy as much as to control carbon. He reminds us of how our humanity is rooted in our one mysterious and life-giving world, and how we can still choose a path toward life. Worth the whole book: the story of his night watching a sea turtle bury her eggs near Cape Canaveral on a beach restored by the very people who built and ignited giant missiles to extend humanity’s reach. —Nora Gallagher

Astray by Emma Donoghue

“If your ethical compass is formed by the place you grow up, which way will its needle swing when you’re far from home?” So asks Emma Donoghue—a 50-year-old Irish writer now living in Ontario, Canada—in the afterward to this collection of historical short stories. “Um, toward murder,” was my answer. Not of someone else, but of myself. During my last ex-pat stint, a self-cure for a UTI went hilariously wrong—two too many liters of fluid in an attempt to pee the bacteria out of my system turned accidental water poisoning. In a country where my visa had expired, I self-diagnosed, self-treated and nearly self-drowned, one water-bloated cell at a time, to avoid checking in at a hospital. Really. It’s quite embarrassing.

Freshly experienced places “reveal all the strangeness in the stranger,” Donoghue goes on to say, and while the new guy or gal who comes to town may be, as she points out, “one of the most reliable of plot motifs,” the characters who enliven her stories progress the plot well, and are fantastically, anything but reliable. The stubborn elephant keeper, masquerading prostitute, gullible attorney, brave escaped slave—they are all strays on journeys of self-discovery, whether they realize it or not.

Somewhere else I’ve read that travel is “the realization that you may have been born in the wrong country.” Donoghue takes this further, as far as it needs to go. Her vagrants cross the borders of countries sometimes, sure, but also, of law, sex, logic, gender and race. Their realization, often, is that they were born the wrong them. We meet them on their way to being found.

When we drift, whether happily, semi-voluntarily or even against our own choice, Donoghue reveals, we learn more about our own weird inner workings than the places we visit (or leave). Those inner workings are the precipice of our identity, and include some of the last truths we want to admit. They’re also the truths that make us wonderfully ourselves. —Molly Baker

War with the Newts by Karel Čapek

When Dutch sailor, Captain van Toch, discovers a race of peaceful, intelligent and human-sized newts off a remote Polynesian island, he reacts like any good colonial capitalist and exploits them for their labor. These newts are industrious and amphibious, their range and population kept in check by sharks. Envisioning himself as a benevolent pater familias, van Toch arms his new “children” with harpoons and knives under the condition that they continue to bring him pearl oysters. The newts multiply in the absence of their apex predator, and van Toch becomes wealthy beyond his dreams. An entrepreneur partner soon sees a larger opportunity and employs the newts in vast underwater engineering projects around the world. The newts are supplied with dynamite, bombs, torpedoes—all the underwater demolition tools needed to build their human masters new islands and empires. The all-too-human justifications for newtploitation follow. Do newts have souls? No! Do they understand love? Of course not. Appreciate music? Silence. But there is something they need to survive. By the time we find out what it is, it’s too late—for us? Or them? Ask Chief Salamander.

A dense but hilarious work of science fiction first published in 1936, War with the Newts is a rare, newly relevant amphibious satire. It begins with a traditional narrative before fragmenting into newspaper articles, scientific papers and anecdotes “gathered” from the archives of a character in the novel. This archivist’s inventor, Karel Čapek (1890-1938), refused to leave his native Czechoslovakia despite being labeled “public enemy number two” by the advancing Nazis. (He died of pneumonia in 1938, before the Gestapo could catch him, but not before coining the term “robot.”) Though the targets of Čapek’s satire are many, his master accomplishment (IMHO) is laying bare the human impulse to ignore long-term catastrophes in pursuit of short-term profits. Čapek saw only too well who the real reptiles are. —Jeff McElroy

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

In Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer—a botanist, member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, woman, mother—offers her stories and reflections on how she has come to know the world. Through each of these lenses, Kimmerer lyrically reimagines the nature of our connection with the places we call home.

“Knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond.”

Braiding Sweetgrass is sincere. It’s about gratitude. It’s about finding beauty in science. It’s about uncovering the complexity of the ordinary. It’s about returning. Most of all, it’s a celebration of our interdependence with the world we inhabit, know and love. In bringing together botany, indigenous wisdom and familial love, Kimmerer rouses a deep sense of responsibility to an earth that is our oldest friend and mentor.

Though subtle, Braiding Sweetgrass captivated me. When I first picked it up, it was around 11 p.m. Once I started reading, I couldn’t put it down. As the sun was rising, I remember texting my friend, “Who needs sleep, I’m currently photosynthesizing.” Progressing through it over the weeks that followed, I found solace that I too could be woven into this intricate web of life alongside the asters and goldenrod, the strawberries and algae.

For so long, I’ve wrestled with the paralyzing task of accepting ecological degradation as my own, but Braiding Sweetgrass offers another path. In moments of sadness, there is an opportunity to demonstrate our resilience. —Rodrigo Bustamante

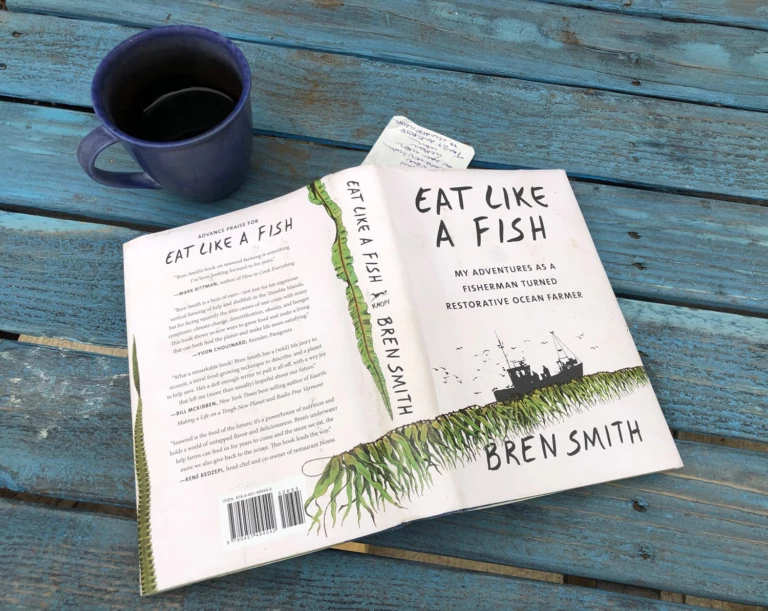

Eat Like a Fish by Bren Smith

Bren Smith swears a lot, always has, and because it’s been a sore point at home, he makes nice at the start of this knockabout memoir. “Let me apologize in advance. I write about the slimy, violent end of things, especially in describing my early years,” he warns. “Convention says I should repent and prefer the sober, inoffensive and violence-free life—but I don’t. The knife’s edge has been good to me.” Yes, and it’s good to us readers, too.

Born in Newfoundland to two ex-pat Yanks, Smith went to sea at 14 having never learned to swim. He loved hunting and killing big fish and might be at it still, only wild fish populations have collapsed; there’s no future in it. A poor student, he tried going back to school, managed a paper ripping Greenpeace for trying to close the Newfoundland seal fishery. On land, he started to “rot from within,” finally returning to the sea to try his hand at oysters. Hurricane Irene wiped him out. So did Superstorm Sandy. Refusing to give up, he began a remarkable run of “blue-collar innovation,” creating vertical, storm-resistant underwater farms with multiple, profitable crops: oysters, mussels, scallops, edible sea greens. The low startup costs and lack of inputs (no fertilizer, herbicides, etc) could make such farms a way for working families to enter the middle class—so long as the demand is there for seaweed and sea veggies. Because these and shellfish filter the ocean and kelp sucks up five times the carbon dioxide of plants on land, they’re also restorative. No, it doesn’t beat the thrill of a chasing blue fin, but Smith’s hit on a way to put seafood on many more tables and cool the planet.

Flip Eat Like a Fish over at your indie bookseller and you’ll find Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard considers Smith “a hero of ours.” If that makes you think this endorsement is meant to score points with the boss, well, I guess I can’t blame you. But I legit loved it, and any suspicion of log-rolling is worth the risk if it gets this book into more hands. Eat Like a Fish is a welcome, briny antidote to climate grief. — Brad Wieners

Jean-Micheal Basquiat edited by Dieter Buchhart

In 1979, Jean-Michel Basquiat was shaking rattle cans and spraying curious epigrams on the bricks of New York City’s SoHo neighborhood. By the mid-80s, he was one of the most famous artists in the world. After his death at the age of 27, Basquiat’s reputation, influence and auction prices only continued to rise, an untitled painting of his selling in 2017 for $110.5 million. Basquiat’s popularity exploded so quickly that his works were hustled out of his studio by collectors while still wet. The result was fame and fortune for art’s prolific “radiant child,” but also caused the work to be dispersed far and wide, making retrospective exhibitions difficult and rare.

In 2018, the Fondation Louis Vuitton scored a major coup with what they termed “the definitive exhibition” of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s painting, drawing and collage, collecting 120 of his defining masterworks. This impressive volume is the document of that exhibition and when it showed up at my local Seattle library branch, I rushed it home. It did not disappoint.

Leafing through this 324-page, large-format book is mesmerizing. The work can barely be contained on the page. Some 30 years after his death, Basquiat can still blow minds, still inspire wonder—even awe—at his rawness, bravery and singular ability to integrate references from all manner of American culture in a way that was/is completely unique and compelling. He posed uncomfortable questions regarding race, history and power structures and provided violent, messy, chaotic and frightening answers, which makes the work as vital, unflinching and in-your-face today as when the paint was still wet. —Steve Duda

Seveneves by Neal Stephenson

When it comes to destroying the world, Neal Stephenson doesn’t half-ass it. In the very first line of Seveneves, the moon explodes, initiating a 5,000-year-long meteor storm that incinerates all life on Earth and leaves the 1,500 remaining humans trapped in a cobbled together clump of space pods bolted to an asteroid. The scenario is intriguing on its own, but it’s Stephenson’s command of the hard science that sets Seveneves apart. The Seattle-based novelist worked as an advisor for Jeff Bezos’ space company, Blue Origin, and Seveneves proved credible enough to satisfy sci-fi-loving astrophysicists as well as Bill Gates and President Obama, who both read it soon after it was first published in 2015.

The high-brow praise is deserved, especially for those who appreciate the plausible edge of speculative fiction. Set within the edges of Earth’s atmosphere, Seveneves is broken into three parts; one and two cover the period between moon explosion and meteor apocalypse as the world embarks on a Hail Mary evacuation onto a Cloud Ark, a self-supported network of “arklets” built around the International Space Station. Over the next three years, the Cloud Ark begins to fall apart (figuratively and literally) in frustratingly predictable power struggles, through which Stephenson explores the limits of technology, the human psyche and our (in)ability to choose the survival of the species over the individual.

Eventually, the human population is whittled down to eight women: the “Seven Eves” and a geneticist who helps them modify and birth their children. Part three picks up 5,000 years later, when the Eves’ descendants have separated into seven distinct races living in a ring above Earth. As these “Spacers” prepare to settle back onto a terraformed planet, they spot something curious—and impossible—wandering the forests below. —Sakeus Bankson

The Overstory by Richard Powers

The first section of The Overstory introduces us to six characters: a Chinese immigrant, an Iowa farmer, a Vietnam vet, a biologist, a patent attorney and a paraplegic programmer in Silicon Valley, with each character’s life attached to a specific tree. Then Powers begins to bring them together in ways that feel organic and intriguing, but something else starts to happen, too. As the story develops, we begin to sense that the novel isn’t about people, after all. They’re just the bait to lure us in. It’s really about the immense, silent and profound ways trees go about their business, and our failure to understand them because they operate on a scale so much grander than our own.

Power’s prose gives them a voice and it’s amazing what you learn. Did you know that trees can communicate? A disease on one edge of a forest will have trees on the far edge producing a resistance. More than once, I found myself rereading passages because I wanted to commit them to memory, and I started to think about the memorable trees in my own life. The more I read the smaller I felt. Trees live, breathe, communicate and think. But you really have to get outside of your own head to appreciate them, and The Overstory does just that—it gets you to stop thinking like a human, and to start thinking like a tree. “People aren’t the apex species they think they are,” Powers reflects. “Other creatures—bigger, smaller, slower, faster, older, younger, more powerful—call the shots, make the air, and eat the sunlight. Without them, nothing.” —Tim Gibbins

Becoming by Michelle Obama

Becoming by Michelle Obama

The other day I was feeling nostalgic (okay, desperate) for the energy and excitement of 2007, when I first felt the momentum building around Obama’s primary campaign. It occurred to me I could reread Dreams from My Father or The Audacity of Hope, but that would make it three times for Audacity, so I turned to Becoming instead. The noun-y gerund title itself promises a reboot; Michelle Obama’s story isn’t finished, even if her time in the White House is.

Obama writes candidly about what a long shot it seemed when Barack first suggested a run for president. “I’d seen enough of the divisions to temper my own hopes. Barack was a black man in America, after all. I didn’t really think he could win.” But she also describes the long conversations they had about real problems in America and what real solutions would look like, and she couldn’t deny him that vision. “He’d been working at this thing, quietly and meticulously, as long as I’d known him. And now the size of the audience would finally match the scope of what he believed to be possible.”

She acknowledges the toll it took on their marriage (couple’s therapy!) and family, the blows she took (“I’ve been … taken down as an ‘angry black woman,’ … A sitting U.S. congressman has made fun of my butt.”), and the realism that helped keep expectations in check. “They would fight everything Barack did, I realized, whether it was good for the country or not.” But that doesn’t mean all has been lost. And Obama delivers what I needed: a convincing reminder to support the candidate in the current primaries who represents what I want America to be, not just the “most electable” one.

“Becoming isn’t about arriving somewhere or achieving a certain aim,” Obama writes. “I see it instead as forward motion, a means of evolving, a way to reach continuously toward a better self.” —Karla Olson