One Patagonia Employee’s Commitment to Protecting the Ventura River

Several years ago, Patagonia email marketing coordinator Steve Wages saw this photograph of two anglers with a big catch of steelhead trout from the Ventura River. The shot was taken in the 1920s.

Those were the glory days, when each year upwards of 5,000 steelies would leave the Pacific Ocean to swim up the rain-swollen river to spawn, and Ventura’s public schools would close down for opening day of the steelhead run.

[Above: The Peirano Brothers with their catch of steelhead from the Ventura River, 1920s.]

It was the days before a dam was built 16 miles upriver on Matilija Creek and engineers had diverted much of the Ventura River into a reservoir behind another new dam at Lake Casitas. It was the days before the groundwater basins around the river were drawn down in earnest – all to provide for a growing population.

[Matilija Dam was built in 1948 for flood control and water storage. Today the reservoir behind its 168-foot cement wall is 90% filled with silt. Environmental interests have been working for years to have the dam removed. Progress is slow and the price tag is high (an estimated $140 million). But with luck and adequate funding, deconstruction could be completed by 2014, giving steelhead access to miles of spawning grounds. Photo: Jim Little]

The photo of the steelhead both surprised and inspired Steve, who is an angler and also a long-term volunteer with Santa Barbara ChannelKeeper’s Stream Team. It showed him what was, and, offered an admittedly hopeful vision of what one day might be again.

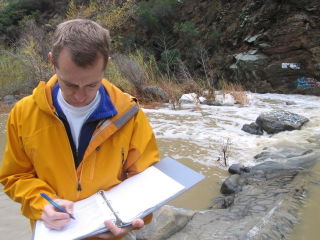

[Steve Wages records measurements gleaned from water sampling on Matilija Creek. Photo: Jim Little]

The first Saturday of the month for the past four years, Steve and his daughter Emily (14) have worked toward that vision by turning out to test the waters of the Ventura River watershed. Along with other volunteers, they visit several of the 15 sampling sites on the Ventura River, Matilija, San Antonio and Cañada Larga creeks, where they measure flow, temperature, suspended solids, dissolved solids, dissolved oxygen, bacteria, pH and nutrients. They also take photos and pick up trash.

[Steve and his daughter, Emily, testing the waters. Photo: Al Leydecker]

Much of the year, the Ventura River, which runs by Patagonia’s Ventura headquarters, is a desiccated specter of its former self. Declared “impaired,” because its flow is often choked with algae, the river is affected by agricultural and urban runoff (fertilizer, soil, metals, trash, bacteria, etc.). A rock quarry, wastewater treatment plant, oil fields and livestock also provide input. After one particularly big rain, Steve says Stream Team volunteers found a dozen tennis balls in one of the creeks. They’d washed down from tennis courts in the Ojai Valley, several miles away.

[The Ventura River flows clear and blue when there’s adequate rainfall. Photo: Paul Jenkin]

The water collected by Stream Team volunteers is analyzed by one of its members at a lab at UC Santa Barbara, and the data is sent to the Regional Water Quality Control Board. The Stream Team has been sampling now for eight years. The data is useful both in measuring the long-term health of the watershed and indicating more immediate problems, such as a spike in bacteria or nutrients. The Stream Team program also benefits the watershed by getting volunteers out into it, which helps ChannelKeeper build a dedicated base of support for watershed advocacy and protection.

“Stream Team is an interesting way to see stream habitat you normally drive right by,” says Steve. “I’ve seen herons, turtles, frogs, crawdads and bass. And of course lots of trash and graffiti.”

In 2008, Steve and Emily’s four years of continuous service earned them Santa Barbara ChannelKeeper’s Volunteers of the Year award. “Those two are hardcore volunteers,” says Paul Jenkin, another member of the team.

Steve says it’s the free pizza that keeps them coming back.

“Not really,” he laughs. “Don’t get me wrong, the pizza’s good, but it just feels good to volunteer: It’s something I want Emily to know is important. And if we can help bring back some of those steelhead, it will be a powerful symbol that the watershed is coming back to life.”