Strength for the Next Disaster

Listen to the story

In a matter of months, a group of activists transformed an under-the-radar environmental threat into a climate villain. The antagonist? A proposed $10 billion liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility along Louisiana’s Gulf Coast known as Calcasieu Pass (CP2). The terminal, just one of 17 similar pending projects in the US, has the potential to release 20 times more emissions than the contested Willow project in Alaska. In the US, the buildout of LNG exports is currently the single largest fossil fuel expansion on earth.

The odds of shutting down CP2 were never in the climate activists’ favor: President Biden has not rejected a single permitting application for a proposed LNG terminal on the basis of environmental impact, and, under his presidency, the US has become the leading exporter of natural gas. But as history goes, the activists persisted, and Biden ceded ground, announcing a pause on all LNG permit applications on January 26, 2024, so the Department of Energy can consider the overall climate impacts of these facilities—and use this information to decide whether these terminals are in the public interest.

This campaign to shut down LNG didn’t appear out of thin air. If there’s an individual protagonist in this story, it’s longtime community organizer Roishetta Ozane, a hurricane survivor and single mom of six kids. Ozane lives within a couple of miles of the proposed CP2 terminal and has been fighting against the LNG industry long before most people saw it as a credible threat. While she’s taking the time to celebrate a well-deserved win, she’s adamant that the environmental movement’s fight to stop CP2 and other projects like it must be matched with a long-term commitment to mutual-aid organizing. In other words: The fight doesn’t stop here.

Ozane, and a puppet inspired by her, lead the #StopLNG protest to confront fossil fuel executives at the New Orleans convention center. The Biden administration announced a pause on new LNG export terminals exactly a week later, on January 26, 2024. Photo: Dayna Reggero

We spoke with Ozane to learn more. Our interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Patagonia: Can you explain what liquefied natural gas is and why you’re campaigning against the industry?

Roishetta Ozane: Liquefied natural gas, otherwise known as LNG, is the process of extracting gas through fracking and putting it in these large pipes—and then heating it at very high temperatures or cooling it at very low temperatures. The fracked gas is shipped from here in Louisiana to other places, where it’s used for energy. But we know living close to these facilities, and doing the research, that this process actually emits methane. It should be referred to as “LMG” or liquefied methane gas because there’s nothing natural about the process of fracking and extracting this gas—and having to change it from its natural form and then ship it somewhere else. There are harms and dangers in each step of that process.

Crude oil and petrochemical refineries line the road leading from Westlake, Louisiana, to Ozane’s home in Carlyss. Photo: Tim Aubry

What is it like to live near these massive extraction sites?

Four out of the seven operating LNG facilities in the United States are located right here in Southwest Louisiana—one of them, Cameron LNG, is located less than 10 miles away from my home. I also live very close to Cities Service Highway, which is surrounded by about a dozen petrochemical facilities. Living here, the air smells like rotten eggs. If you drive further down, [the smell] turns from rotten eggs to very harsh chemicals. If you’ve ever smelled Clorox or bleach, it smells like that in the air. When people come here to visit, they get headaches, nosebleeds, itchy and watery eyes, and itchy and burning throats. My two youngest children have asthma and other respiratory issues. My 17-year-old was just diagnosed with epilepsy, and there’s traces of mercury in his blood, which may have come from him eating contaminated fish.

It’s always loud. It sounds like a train is running through the backyard. Sometimes, it sounds like there’s a storm outside when there’s no rain or no storm happening. And, when it is just a rainy day, there’s still cause for concern even if it’s not a major hurricane because the infrastructure here is so horrible that communities will flood. When these [fossil fuel] facilities are built, they can wipe out entire neighborhoods. That’s what happened in a town called Mossville, Louisiana, a small, predominantly Black neighborhood that was founded by slaves. One of these facilities came in and pushed those citizens out, forcing them to move to another community—all of their culture and their history is now destroyed. And it’s the same thing that’s happening in Cameron, where they want to build CP2.

If approved, what impact would this one LNG export terminal, Calcasieu Pass 2 (CP2), have on our climate and local ecosystems?

The construction and the operation of CP2 would have both direct and indirect impacts on our climate as a whole. First off, CP2 would be the largest LNG export facility in the United States and result in excess methane emissions, an extremely potent greenhouse gas. CP2 would also obliterate acres and acres of wetlands, home to wildlife and fisheries. The wetlands are where our fishermen and shrimpers make money to provide a living for their children. In the last few years, we had two major hurricanes right here in Southwest Louisiana: Hurricane Laura and Hurricane Delta. I myself lost my home to Hurricane Laura and Hurricane Delta. And so, we know that if we lose those natural storm surge protections, like our wetlands, like our dunes and like our cheniers—then we don’t stand a chance of surviving these hurricanes that are increasing in frequency and strength.

Now that President Biden has placed a temporary pause on new LNG export permits, what next steps do you want to see the administration take in support of frontline communities who will still be impacted by the LNG industry?

We want the federal government and the oil and gas industry to stop perpetuating environmental racism by constantly approving these LNG, methane-emitting projects in our community. We believe that frontline communities, those who are most directly impacted by these industries, should have a seat at the table when it comes to determining whether these projects are in the public interest. Our voices and experiences are invaluable in shaping these decisions. We’re also calling for the reinstatement of the ban on exports—it’s crucial that we not only halt the permitting of these facilities but also prevent the export of fossil fuels altogether.

A massive petrochemical plant, Westlake Chemical, operates across the railroad tracks from a community recreation center in Mossville, Louisiana, where Ozane’s kids played basketball and swam as young children. Photo: Tim Aubry

Researchers have documented the ways environmental racism enables the fossil fuel industry and, in effect, fuels the climate crisis. How do you see racism interplaying with the expansion of fossil fuels in your neighborhood?

When you look at the situation that happened in Mossville, the wealthier, whiter people who lived across from the train tracks, closer into the city of Westlake, were offered more money to sell their land and their home than the Black people were, who lived inside of Mossville, even closer to where the facility is. And these are the types of environmental injustices that we face. It is flat-out environmental racism that has been happening for decades. If you take a slave map, or a map of old plantations, and you put it directly on top of a map of industry currently, it’s clear to see where this industry is located and who’s impacted the most.

Can you explain more about how environmental racism is impacting people of different races and incomes?

Environmental racism is impacting people of all color, but again, who it’s impacting the most are low-income Black, Brown, and Indigenous People of Color. When you come to Southwest Louisiana, it is so clear to see where the majority Black area is and where the majority white area is. Now, I won’t say that white people aren’t impacted—but it’s the low-income white people who can’t afford to move away from the industry. It’s the low-income white people who are relying on the land. It’s the fishermen, the shrimpers, the crabbers—and also, low-income Black people, who have no choice—who are offered the least amount to move. Because of the greed of our legislatures—and the greed of the oil and gas industry—environmental racism is spilling over. And now it’s impacting an even larger group of people. Because you can’t separate water. You can’t separate air. When you think about it: I might be living close to this LNG facility, but it has to be transported somewhere. When it’s transported, the spills and the leakages and the smells are traveling with it.

We saw the train derailment in Ohio. The same chemicals that were on that train are produced in my community of Westlake, Louisiana, by a petrochemical company called Westlake Chemical. The facility that makes this product [vinyl chloride] has had several explosions in the last few years. So, who does that impact? That doesn’t just impact me, who lives next door to it. When those explosions happen, they’re felt farther than just my community. And the people who were just labeled as “throwaway people”—we’re the ones fighting the hardest. But we’re contributing the least to the problem. In our fight, we’re not just fighting for us and our children. We’re fighting for everyone and everyone’s children.

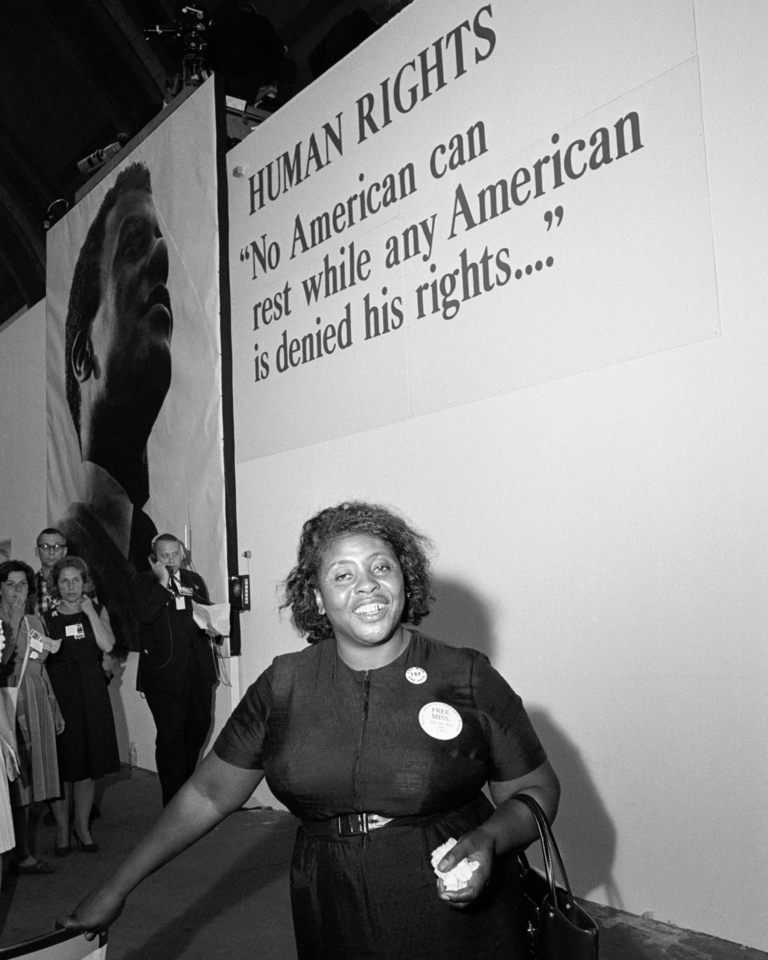

Fannie Lou Hamer at the 1964 National Democratic Convention, where she served as a delegate of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and delivered testimony about systemic anti-Black racism in the South. Photo: Bettmann | Getty Images

Can you share more about your journey to activism? Is there one moment or experience when you raised your voice and you really felt like you made a difference?

I’ve always been very outspoken and just went against the grain. I’m from a small town called Ruleville, Mississippi, home of Fannie Lou Hamer. Fannie Lou Hamer was a civil rights activist who fought for women’s rights and voting rights. She faced opposition and danger, but she continued to fight for the citizens of Ruleville. And that is what’s in my blood. My grandmother was also one of those activists who would march and helped to fight for Head Start. And still today, she helps people register to vote and makes sure people get to the polls. So, these are the type of things I grew up with.

Moving from Ruleville—surrounded by cotton fields, greens, beans, rice and catfish farms—to Lake Charles in 2003 was a big change for me. But I knew that I was here for a reason. So, I started getting involved in the community. But I always had questions about these industries. I was like, why are there so many polluting industries? And what do the people do? And why are there a lot of cars in the parking lot, but you don’t really see the people? Why is there fire in the sky? What is the smoke? And no one really would answer the question.

Then I remember there was an explosion at one of [the nearby petrochemical facilities.] And I had two children at the time, and I was newly married. I was scared to death. I grew up in the church, so I thought it was just, like, the end of the world, you know? Like Jesus was coming back, and the world was on fire. And it took about three years before that class-action lawsuit was settled, and each of us only got $500. Knowing we could potentially in the future have cancer, lung disease, respiratory issues … $500 is not even enough to pay a medical bill. I was like, “Are you telling me this is what my life is worth? $500?” And I haven’t been quiet since. That was the moment that I transitioned from asking questions to feeling like they don’t care about us. How can we stop them?

How do you feel like these experiences shaped your identity as a community organizer?

I had to really learn what was happening, and I had to get over my fear of feeling like this small little Black girl who couldn’t take on these big industries. I realized—wait, I’m not fighting a building. I’m not fighting an industry. I’m fighting other people. These are other people. They’re human beings, just like me, who go into a room and make a decision that impacts me without me being at the table. So, if I want to make a difference, I’ve got to figure out how to get at the table. It wasn’t until 2020 that I realized that all of the community work that I had done in my life was directly intertwined with environmental justice. I just had never heard the term environmental justice before.

The reason I started my mutual-aid grassroots organization, the Vessel Project, four years ago is because I can relate to the community. I’m a Black woman; I was a victim of domestic abuse; I lived next door to industry. I’m not trying to just stop the oil and gas industry. I’m trying to make this community better—so that we are strong enough to fight against whatever threat comes next.

So, what is mutual aid?

Mutual aid is about providing assistance to those who are most in need—and providing that assistance immediately. If there is a low-income community with little resources and a disaster hits—and takes away the very little resources they had—who’s going to replenish them? Who’s going to help them get back to where they can fight? I can’t go put out my neighbor’s fire if I’m putting out my own fire. But if I can get my fire under control, and make sure my house isn’t burning down, then I can go help my neighbor. So, the only way for us to survive is to help each other through mutual aid. If the Vessel Project can pay your rent, let us pay your rent. Because now you don’t have to worry about your rent being paid. If we can get groceries for you to feed your children, now you don’t have to worry about that. If we can get you tires for your car, if we can help you fill out that job application, complete a resume, get warm clothing for the winter months or cool clothing for the summer—that is one less thing you have to worry about in a society where you feel like no one cares about you.

Ozane addresses a crowd of supporters at a New Orleans #StopLNG protest, organized by the Permian Gulf Coast Coalition. Photo: Dayna Reggero

If we just focus on CP2, and we win against CP2, guess what? Some other industry is going to come through, and meanwhile, we put all that energy into CP2. But if we put all our energy into the people of the community—making sure that the people are strong and resilient and have the resources that they need—no one else will have to come in and fight for them because they’ll be ready to fight for themselves. If we make these people whole, and we provide this mutual aid for them, they’re going to want to fight against anything that’s going to put them back in that situation. And it’s a tough thing because you have to make people understand this approach to community organizing is not bribery. It’s helping a person get in a position where their eyes are open; where they can see the things impacting them; and they decide to fight against those things because they don’t want to be in that situation again. Because they don’t want people coming here who are going to harm them.

Can you tell us about the visions you have for yourself, your family and those around you? And all frontline communities around the world?

My vision is for communities to be able to stay together and families to be able to stay together, if they choose, in those areas they grew up in. I imagine there being more green spaces for children to play. I envision being able to enjoy the natural resources of this area. Being able to plant a garden and eat from that garden. Being able to go fishing and crabbing—and eat those crabs and those fish. I imagine the community coming together in times of destruction. We can’t stop hurricanes, right? But when those hurricanes occur, I imagine people having the resources that they need to come together and ensure that we can build back resiliently, so we aren’t impacted as much if another hurricane comes somewhere down the line. This is part of the reason why we need grassroots, frontline community organizations like the Vessel Project—who live in the community, who know the people, who know the needs, who the people trust—to have the funding and resources available to meet those needs.

What’s keeping you going for the fight ahead?

With this fight, the thing that keeps me going is my faith. I always believe we’re going to win, even when we don’t win that particular permit denial. I think we win in building people power. We win in building community. We win whenever we build attention to our area and we get people to come here and see what’s happening. So, I think we always win, even if the permit is granted. And we don’t stop fighting. Because again, my goal is not just to stop CP2; my goal is to make sure my community and communities like mine are supported with the resources they need to fight against extraction itself.

Support the Vessel Project

To support mutual aid organizing in Southwest Louisiana, consider donating to the Vessel Project.