Small Is Still Beautiful

Tough and uncertain, organic cotton farming accounts for less than 1 percent of US cotton production. For this family, that’s why it’s a calling.

Aaron Vogler didn’t want to be a farmer. “Compared to other kids’ summer jobs, it was hard work being in the fields,” the reserved 34-year-old says. “But I guess it was good to be out there with my parents and my sister. We were miserable together.” In 2000, he left his family’s third-generation farm for college, intending to get into banking. To his surprise, though, he returned in 2004, and never left. “I could quit later, I figured, but I never did,” he shrugs. “At some point, it didn’t seem as bad as I remembered it.”

On the High Plains of northwest Texas, long, hot summers punctuated by rainstorms give way to short, cold and dry winters—a great climate, it turns out, for growing cotton. And the extremes seem to have toughened up those who work this land, too, leaving them humble and quiet. Like Aaron, his folks, Jerry and Darlene Vogler, were surprised he came back to stay, but they were relieved, too. “We think about it a lot,” says Darlene. “What would happen if Aaron weren’t farming it? Most farmers are not equipped to farm the way we do.”

The Voglers are one of a few families that helped establish a small cooperative of organic farmers called the Texas Organic Cotton Marketing Cooperative (TOCMC) in the early 1990s, when Patagonia first switched to only using organic cotton. Starting small, but working together in numbers, the cooperative has been able to grow their annual yield from around 3,000 to 10,000 bales. To start 2021, there are 35 small family producers that belong, and they range in size from 17,000 to 20,000 acres. The families in the cooperative have helped support the less than 1 percent of cotton that is produced organically in the US today, even while most of their neighbors in America’s Cotton Belt still grow with conventional cotton methods. “We’re small fish in a big pond,” says Darlene.

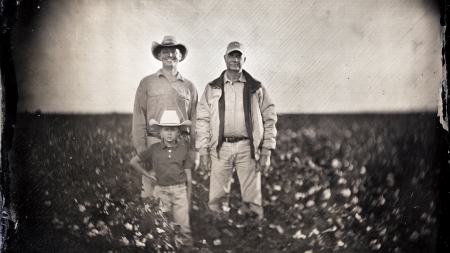

The Voglers’s family farm has been producing organic cotton since the early 1990s. Photo: Giles Clement

Conventional cotton farming uses synthetic pesticides that can harm the people working the land, degrade soil and contribute to topsoil loss. Organic cotton farming aims to work with nature rather than against it and relies on more traditional farming methods such as hoeing. While avoiding harmful chemicals is often a motivator, the promise of financial security is what brings many farmers to organic. Once certified, they can sell the crop at a premium. “I guess I hope that if at some point conventional doesn’t pay the bills, they’ll consider another way,” Aaron says.

Getting beyond 1 percent organic cotton production remains an uphill battle, but according to the Voglers, the change starts with demand. When more consumers are willing and able to pay more for it, more people will be willing to farm this way. “I think people that pay out a little extra money for organic are making a little sacrifice for the greater good, just like we do,” says Darlene. “We don’t cover nearly the number of acres of land other farmers do, but since we can now afford to do it this way, it’s worth the sacrifice. Because this is the way we prefer to farm. This is the kind of world we want to live in.”

“At the end of most days, I feel that I’ve done something good,” Aaron says. “It’s clean living out there. And being able to see the plants and soil healthy, the insects out there safe, and how everything works together and coexists, it’s just nice. It’s a good way of life.”

This story was first published in the Patagonia Spring 2021 Journal.