Singing to the Sake

Harmonizing with invisible organisms, and other Japanese brewing wisdom.

All photos courtesy of Terada Honke

Terada Honke, a 17th-century sake brewery in Chiba Prefecture, Japan, makes sake for Patagonia Provisions as part of our natural wines program. Masaru Terada, the 24th-generation owner and brewmaster (toji), describes what it’s like to harmonize with unseen microbes—and why it defines his life.

I came to the brewery in 2003, through my wife, Satomi, who was born and raised at Terada Honke. My father-in-law, Keisuke, accepted me and showed me unconditional love. He would spend an hour or so with me after dinner, talking about fermentation, how to have a good heart, how to run a company and the importance of sensing the unseen world.

To become part of this family, I changed my surname to Terada. There is a tradition of sons-in-law working at Terada Honke, including my father-in-law and his predecessor. There are many reasons why the brewery has been able to continue, but one factor is the sons-in-law, who brought new ideas while cultivating a state of mind that allows for a dialogue with invisible microorganisms.

We make sake in the wintertime, after the rice harvest, and do it the traditional way—with our hands. One of our methods is the kimoto process, using a yeast starter made with microbes that live in the brewery. We believe this tradition goes back 300 years.

The kimoto process begins with our rice, full of light and soil energy, grown in local fields without any pesticides or synthetic fertilizers. It’s already been polished, so the grains are translucent. We rinse the rice thoroughly, swishing it to remove loose bran, and then soak the grains until they turn white. The water comes from our well at the foot of the Kozaki Shrine, surrounded by a forest that is hundreds of years old. The water seeps into the well through a network of ancient tree roots and fungi, carrying microorganisms and minerals vital to the brewing process.

All water used for the sake comes from the brewery’s well at the foot of a centuries-old shrine, surrounded by ancient forest. Tree roots and underground fungi enrich the water with microorganisms and minerals.

We limit the use of machines in the brewery. By using our hands, we can engage all five senses to better understand the daily differences and nuances in the fermentation process. It wasn’t always this way. During World War II, the rice shortages normalized cheaper ways of making sake using brewer’s alcohol and preservatives, and that practice continued even after the war. Around 1985, my father-in-law fell ill, and his failing health triggered thoughts about the processes of decay and fermentation, and how they are similar yet also opposite. He decided to return to traditional methods for making sake that are filled with life and invigorated by microorganisms and the power of nature.

We steam the rice early in the morning. The soaked grains are placed over a large steamer going full blast. They grow plump, soft and slightly chewy and have a sweet, slightly roasted fragrance that wafts through the cellar—that’s how we know when it’s done. We scoop the steamed rice onto a hemp cloth, spread it thin and repeatedly massage it with our hands to expose it to the chilly morning air.

Steam rises from a large wooden vat as the grains inside grow plump and chewy-soft. The vat is used to steam nearly a ton of rice every day.

A cellar worker at Terada Honke sake brewery shovels out the freshly steamed rice to be spread and cooled. Much of the work at the brewery is done by hand, allowing workers to fully use their senses as they guide each step of the sake.

After steaming, the brewery crew cools the rice by spreading it thin and turning it with paddles. If the rice is too hot, it will be inhospitable to the all-important koji culture.

Once the rice is cool, we move part of it into a separate room to make the rice malt (koji). There, we spread it out again and sprinkle it with Aspergillus oryzae mold, which drifts over the rice in a delicate yellow-green cloud. Over the course of three days, enzymes in the mold break down the starch into sugar. The finished rice malt is very sweet and smells like chestnuts.

In a special enclosed room, the Aspergillus oryzae mold is shaken over the cooled rice. The mold converts the rice starch to sugar, creating sweet rice malt (koji).

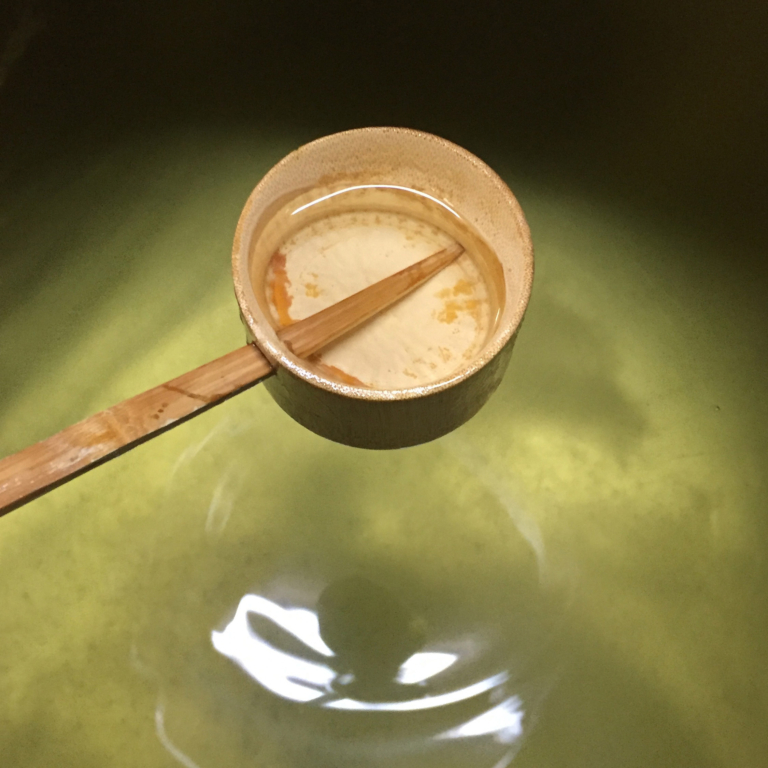

Next comes the yeast mash (shubo), a starter that we’ll use to ferment the sake. In small wooden tubs, we add the rice malt plus more plain, steamed rice and well water and mash it all together using long poles with wooden blocks on the ends. The mashing time is about 15 minutes, and we do it three times. Two cellar workers are in charge of each tub, and they coordinate their rhythm by singing motosuri-uta, the old rice-mashing songs, which go back hundreds of years. By singing, the brewers’ hearts become one and teamwork improves. I even think that the microorganisms ferment more energetically when they hear the songs!

The liquefied mash goes from the small tubs into one bigger tub. It spends 40 to 50 days there, absorbing lactic acid bacteria and yeast from the air. These organisms feed on the sugars as the temperature gradually rises. As they feed, the yeast produces alcohol and the bacteria creates lactic acid, making an inhospitable environment for microbes that cause spoilage, therefore protecting the sake from decay. The fermentation gains momentum, and the entire surface of the tub seethes with bubbles—you can hear a quiet popping and hissing if you listen closely. When it’s finished, it will be intensely sweet, sour and vigorously alive, with more than 200 million yeast organisms per milligram.

For the final step, the yeast mash is transferred to an even bigger tank, along with more steamed rice, rice malt and water. The mash starts the fermentation, consuming the added food and propagating vigorously, producing additional alcohol. When the alcohol level reaches between 17 and 20 percent, fermentation is complete, and we squeeze the finished mash (moromi) in a hand-operated accordion press.

Right away I taste it. If the sake is successful, its life unfolds as scenes in my mind, from the sowing and harvesting of the rice to the brewing, all connected to that taste. This kind of sake, made in the traditional way, has a tangy umami flavor and a vitality that awakens your body.

Tasting the newly pressed, golden sake. Generally, sake is filtered through activated charcoal to remove color and any “off“ tastes before bottling; Terada Honke skips the filtration to preserve the natural flavor. At this stage, the sake has a fresh, lively fizziness and a distinct flavor of rice malt.

In the world of sake, winning a prize in a competition can be an easily understood success. However, at Terada Honke, we believe that the world of microorganisms is based on the principle of symbiosis, not competition, and we have maintained our stance of not entering any such contests. Instead, when Terada Honke’s sake was unexpectedly used at Noma in Copenhagen, said to be one of the best restaurants in the world, I felt very happy that our efforts were recognized by those who strive to be the best at what they do.

There are always failures, too, especially when you make sake with the help of bacteria. The acidity may rise rapidly, or the yeast may not ferment and create alcohol as it should. Sometimes we may have to refrain from selling. This can be very damaging from a business standpoint, but when I observe such mistakes, I feel they tend to happen when we get greedy and try to increase the volume for increased sales. The microbes tell us how to find the proper volume.

My main responsibility as toji is to create an environment for beneficial microbes and cellar workers where all can collaborate comfortably and happily. Natural fermentation does not always go as planned. However, the experience gives us ingenuity for the next challenge, and when we find a taste that is beyond our expectations or even our imagination, it’s very joyful.

Owner and brewmaster Masaru Terada checks the morning’s freshly steamed rice. It’s critical that the grains reach just the right moisture level and softness to welcome the Aspergillus oryzae spores and encourage them to grow.