Running With My Devils After a Health Scare

I remember running the 50K and getting off course but fighting back into third place, and I remember that it was hot… hotter than hell. And then… and then nothing…

I don’t remember collapsing. I have no memories of kicking off good-Samaritan runners who pinned me down to the Prairie floor. I have no recollection of coolers of ice poured over my torso… packed around my groin, armpits and neck. I don’t remember soiling myself. No memories of my clothes being cut from my body in front of dozens of strangers. No memories of the ambulance ride to the local clinic or the life-flight to the Mayo Clinic. I don’t remember any of it.

Three days later I woke with a plastic tube shoved down my throat. “What the…” I tried to spit out, but the words slipped out as a groan.

“Cough it out. Cough it out!” shouted a blue silhouette as the corrugated tube ripped across my vocal cords. I chased the tube with vomit and then heard the familiar voice of my wife, calming my anxiety.

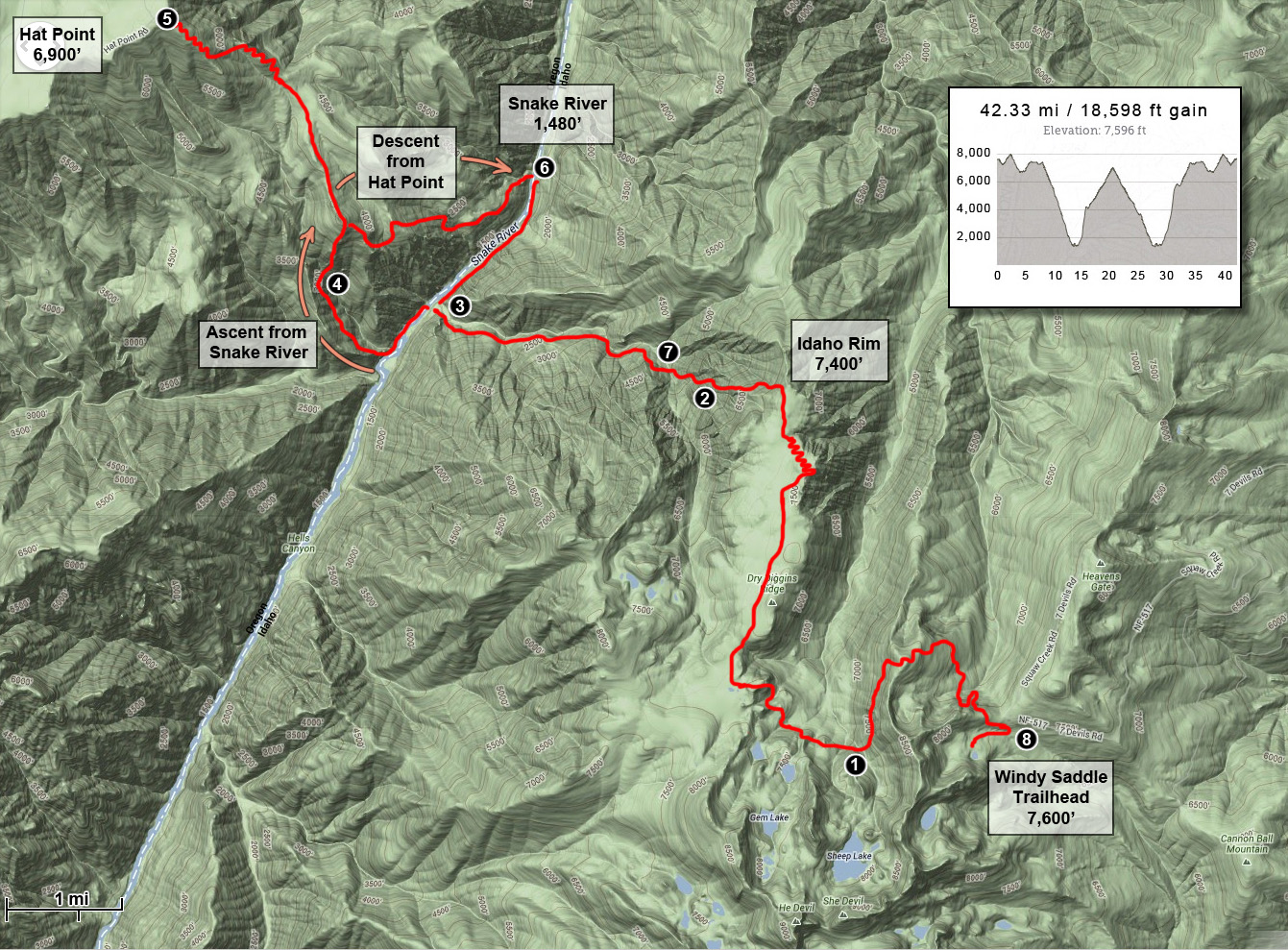

Above: Mike James in Hells Canyon, Idaho. All photos by Steve Graepel

A few hours of stats and piecing together the previous few days, I struggled to my legs.

“I gotta take a leak.”

Exhausted from the five-foot journey, I closed the door and stared into the mirror. Almost overnight I had morphed from the fittest I’d ever been into a Jenny Craig “before” picture. I cocked my head left and ran my fingers down my neck, teasing three stitches closing a line into my subclavian. An ER doc used it as a port to funnel seven gallons of saline into my limp body. I lifted back folds of bloated belly, straddled the toilet and a black, tar-like fluid burped into the bowl.

Evidently, I redlined three miles from the finish line – burning up into systemic failure. My muscles ripped apart at a cellular level, pouring toxic myoglobin proteins into my bloodstream, gumming my kidneys. Simultaneously, all remaining fluids were diverted to my damaged muscles, kicking my already compromised kidneys deeper into failure. In a last ditch effort, the docs flooded my system with saline to frack my glomeruli. Three days later, I was literally pissing myself away.

Afton Alps was the last number I pinned to my chest. Accepting that mind is stronger than body, I’ve since run my endorphin demons sans clocks and competition, giving wide berth for any Icarus complex. Ten years later, I found myself turning back to my maps for inspiration and celebration.

____________________________________

A few hours from Boise, the Snake River arcs like a scythe across Idaho’s fertile belly before cutting north into the benchland fells that separate Oregon from Idaho. Descending through a staggering five topographical provinces, Hells Canyon is quietly known as the deepest gorge in North America – deeper than the Grand Canyon – falling and rising 8,000 feet inside a 10-mile span. Because of its topography, the area is entirely roadless and was established as Wilderness back in 1975 as part of the Hells Canyon National Recreation Act.

My goal was simple: run the first rim-to-rim and back of Hells Canyon… “to hell and back.” One thing was for certain; I wasn’t going solo. The crux might have been finding the right partner. Enter Mike James.

A Billings-based airplane mechanic, Mike was training for a Fall 100 between shiftwork at BOI. I met him through a friend of a friend over Facebook. I hesitantly pitched Hells and he signed on without flinching, “sounds like a hoot.” I couldn’t tell who was more lunatic fringe: me for proposing the out and back or Mike for accepting my blind date.

A week later our toes perched over the Windy Saddle Trailhead on the Idaho side. We agreed to take it slow and easy. We had all day after all. The trail immediately cascaded down a series of steep switchbacks through a forest of fire-scarred tree trunks and under the haunting granite spires of Seven Devils.

He Devil, She Devil, The Ogre and The Imps – the names source back to grim Nez Perce lore where “the devils” made a yearly pilgrimage from the Blue Mountains seeking children to eat. Sly coyote dug deep pits, trapping the devils and turning them into monoliths as an epithet for everyone to remember them by. To prevent the ogre tribe from future pillage, a deep trench – Hells Canyon – was dug.

After rounding the Devils, the trail abruptly butted into the void where we watched the topography plunge 6,000 feet beneath us. I could just barely make out the lacing of Upper Bernard Falls, class V rapids that frothed above our proposed crossing point. Our eyes tracked upwards through the smoky haze to the Oregon side, where a lone tower pierced the adjacent rim’s skyline.

“Hat point, our turnaround point,” Mike pointed out.

Identifying our turnaround point didn’t make it any easier to swallow; the reality of 20 miles, 8,000′ and still only being halfway done weighed heavy in the gut.

A sun-bleached line traced across the grassy slopes below us, marking the route to the river. We pointed our toes downhill and took the plunge into Hells Canyon, measuring progress in increments of 1000:

- 6,000′: a lush undergrowth choked the trail

- 5,000-4,000′: conifer stands transitioned to grassland

- 3,000′: tunneled under hackberry thickets

- 1,400′: spilled us out into the valley floor

The river basin gave us a quick glimpse of the river’s long history. Prehistoric pictographs stained the gorge walls, remnants of a 7,000-year-old stone shelter crumbled under feral orchards. The relatively youthful McGaffee cabin – abandoned nearly 100 years ago – stood proudly over the riverbank. Just then the cheer of people broke the steady rush of the river’s din.

“Rafters!” I shouted.

The route across the canyon was fairly straightforward. But we still had to negotiate the river and our options were slim: swim it or hope for a ride across the Snake. As we broke out onto the gritty beach, a team of rafters was mooring for lunch. We thumbed a ride with the scouting raft, shuttling supplies to their evening camp.

“Where you boys heading?” asked our pilot.

“To the top,” I pointed.

The guide strained to follow our line. He looked at our meager 20-liter packs and shook his head. “You boys have fun,” he chirped as we stepped into Oregon.

On the Oregon side we followed the historic Nee-Me-Poo trail south – the same trail Chief Joseph led his people into Montana on while fleeing General Howard in 1877 – until it forked with the wispy Hat Point trail.

To call it a trail would be generous. Climbing up through steep rhyolite gendarmes, it hardly qualified as a game trail – testament to how devoid of visitors the region is. We negotiated our way onto a grassy plateau where routes appeared to converge under the canopy of Ponderosa Pines and upwards towards the Oregon highpoint. Five hours later we climbed out onto the fire tower deck we spied earlier that day.

From the top, we traced the day’s events back up to the Seven Devils, perched far on the horizon line. Thunderheads over Idaho, Mike suggested we poach a night’s sleep inside the lookout and run it out the

following morning. Low on supplies and time, I was eager to cash in on the remaining light and see how far we could get.

“If we can cross the Snake during daylight, we could walk to the truck before first light,” I pitched. Mike shrugged and we quickly ran it down the familiar trail and out onto the grassy plateau.

Deep in the canyon basin, the towering walls prematurely stole our daylight, slowing our pace to a crawl. We knew we had to negotiate a series of benches before we found the river; we toggled from headlamps to darkness to triangulate our position.

As we rounded down the first bench, I heard Mike’s shoes struggle to find traction followed by the skid of body mass. Mike righted himself and hobbled down to me where he flashed his headlamp across his right side. Shoulder to thigh, he was studded with spines accumulated from sliding through a patch of prickly pear. “Good thing the cactus broke my fall,” he said, making the best of it.

“Seems like a good time to stop,” I responded. We spent the next 45 minutes extracting quills until Mike felt he could make it through the night. We dozed off under the glow of the Sheep Fire illuminating the sky behind the Idaho rim.

The rally of Chucker greeted the morning light. I turned to see Mike perched on a rock, pulling spines from his ass. “You ready to roll?” he asked as he shoved a glove between his tights and side to buffer the pain.

We gathered our scant supplies and descended the remaining elevation to the river in search of the safest crossing point. In spring, the Snake can run upwards of 60,000 cfs. It runs much lower in fall – about 15,000. Dam fed, we were hoping the morning flow would be lower yet, but it was still running strong. We found a wide stretch pooling well above downstream objective hazards, stuffed our clothes into our packs and dove into the river. The flow was swifter than it appeared, pushing us lower than our desired beach. Exhausted, we pulled our waterlogged bodies over river boulders and onto dry land where we wrung ourselves out before settling into the long and painful climb up to the Idaho rim.

We separated some on the ascent, each gamifying our own extraction from Hells. Myself, I reflected on the last 10 years. Since Afton Alps, I’ve lost a gallbladder (they say directly related to heat stroke), moved across the country and had two kids. I no longer run on hubris. But wanderlust – left unchecked – it can spread like a noxious weed. I’ve hoed a sustainable line by weaving ultra with a bit of mountaineering, cycling and paddling. But in the end, it always comes back to whom I’ve shared the adventure with. Mike and I came to the canyon as strangers, tethered together by a line on a map strung between two highpoints. 36 hours later, Mike and I climbed out of the canyon as fast friends, having plucked one of the finest plumb lines in North America.