Paths Through the Uncertainty

A climber remembers her first experience with the

unexpected on Thalay Sagar.

In the spring of 1986, when I was working at the American Alpine Institute, I read a note passed to me from a fellow guide, Andy Selters. These were the days before cell phones or emails, and I lived out of my Subaru, so life happened at a different pace. “Let’s meet at the office next week after work. I want to do a new route on the north face of Thalay Sagar in India with you this fall.”

Although I had climbed the Cassin on Denali and some hard routes in Peru, this would be my first expedition to the Himalaya. It would also be my first to a remote peak with someone I barely knew, and one where we would also travel with a full team, including a cook, liaison officer and 17 porters.

The gear prep began in earnest a few weeks before the trip. We sewed our own duffel bags and carefully hid our fuel cartridges inside them. We built a homemade hanging stove kit. Then, with the help of a friend, we designed and built our own portaledge because there were none on the market light enough. Ours was four feet wide and six feet long, and had a triangular footprint. We tested the ledge by hanging it from a store-front balcony and climbing inside. Then friends on the sidewalk swung it violently and threw Styrofoam pellets at us to simulate a snowstorm.

As well prepped as I thought we were, every day in India was an adventure. We traveled from Dehli to our trailhead in Gangotri in the back of a public truck, brightly decorated and painted with tassels. The trip took four days. Gangotri is where the Ganges River comes out of the glacier. It’s also a holy place for Hindus.

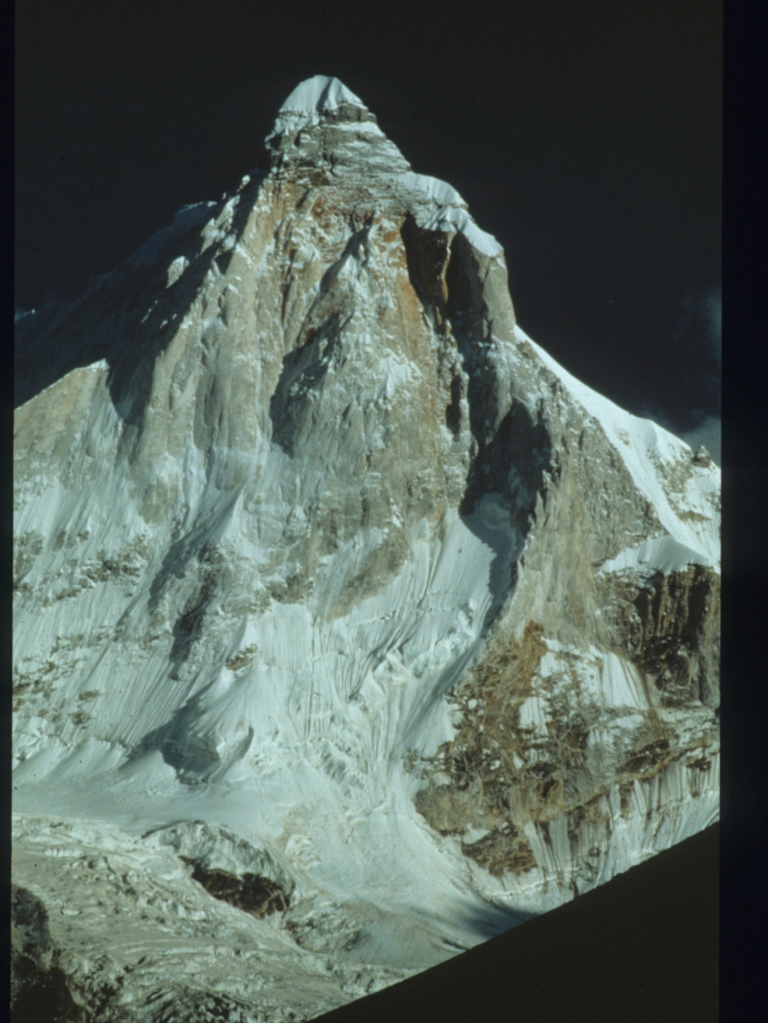

After a four-day hike, we neared base camp and first laid eyes on the impossibly steep north face of Thalay Sagar. We had an unspoken rule that if you don’t have anything positive to say, don’t say anything at all. The peak was terrifyingly majestic. We didn’t speak for hours.

Once we got our wits about us, we started acclimatizing by carrying loads up through a giant talus field to the advanced base camp, high on the glacier at the foot of the face. Always in shadow, the temperature hovered around minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit. With a stomach full of butterflies, I exclaimed, “I’ll take the first lead.” Being able to focus on one pitch at a time put my mind at ease. A 2000-foot ice cone led up to a golden granite headwall, topped by a black shale band and a summit snow pyramid. We had chosen an alluring dihedral that bisected the face.

As they waited out the storm, Kitty and Andy tried to focus on the small things. Photo: Andy Selters

We were nearing the shale band, at about 21,000 feet, after three days of climbing, when a storm blew in. At first we welcomed the rest and decided to ration our food and continue once the storm ended. After four days of lying on our backs on our 4′ x 6′ portaledge, in unrelenting wind and snow, we realized that we were in a serious situation.

The storm was intensifying and the slope high above could not sustain the load of new snow. The first avalanche that poured over our portaledge was terrifying. One corner of our portaledge was already broken because we hadn’t anticipated the forces that would be put on it, so it was tied together with webbing. Also, we had never anchored a portaledge with ice screws before—or heard of anyone who had. As the snow pounded the fly over us, I closed my eyes and prayed. The avalanches became a regular occurrence. We couldn’t go down until the storm ended. How long would it continue? How long could we survive? Our lives were suspended in limbo and we were completely out of control of our own destiny.

From that moment on, in order to create some semblance of certainty, we developed a daily routine—up at 9 a.m. for instant coffee. Then Andy, who has an encyclopedic memory, would recite the History of Alpinism Part 1, followed by a lunch of ramen and a nap. We woke at 2 p.m. for the History of Alpinism Part 2. At 4 p.m. we started a two-hour process of filling water bottles and a pot of water, a circus act which involved leaning out of the portaledge and chopping ice off the wall with one hand and catching the falling chunks in a stuffsack with the other hand. Dinner followed, then some small talk and sleep. We were lethargic from lack of calories, and sleep was a welcome escape. We never voiced feelings of fear or wishful thinking, knowing it wouldn’t change our circumstances. Instead, we focused on being grateful for small things like morning Nescafe.

The mountain. Photo: Jay Smith

After eight days, the storm finally subsided and we emerged from our small portaledge like butterflies from a cocoon. The descent was long and arduous. When we stumbled into base camp, Andy ate until he passed out, satiated for a while. I watched him quietly snoring and thought, whether you are a “thrill-seeker” or not, life is an adventure—the unexpected happens.

Through it all, and to this day, I appreciate being able to choose how I react to my circumstances and the ability to create peace in the midst of uncertainty.