Made to Work

A short history of gear designed for very specific reasons.

Listen to the story

Nearly everything we make is designed and constructed with input from the various athletes and communities who use our products. Our ambassadors test gear and sometimes make repeated requests for very specific features. Our network of field-testers then takes the prototypes designed by our R&D technicians and puts them through highs and lows to get us to the point where we’re making the best products for a specific use. Even though a general tenant of our product design philosophy is to make products that are versatile—running tights that work for yoga or a jacket you can ski, climb and fish in—everyone gets excited when we take the opportunity to make something intentional that’s also built for a unique set of circumstances. Sometimes it’s a product that meets the borderline neurotic but also exceptionally well-considered needs of an elite alpine climber. Other times it’s a request we’ve heard over and over again. Occasionally, it’s an opportunity to rethink the entire way a product is made.

Here are a few examples over the years:

Captain Liz Clark manages gear on deck while testing out the Big Water Foul Weather kit. Tahiti. Photo: Christa Funk

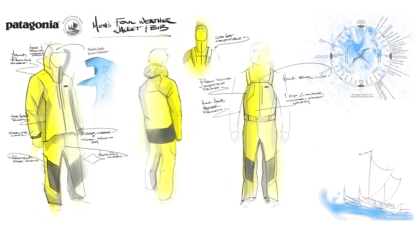

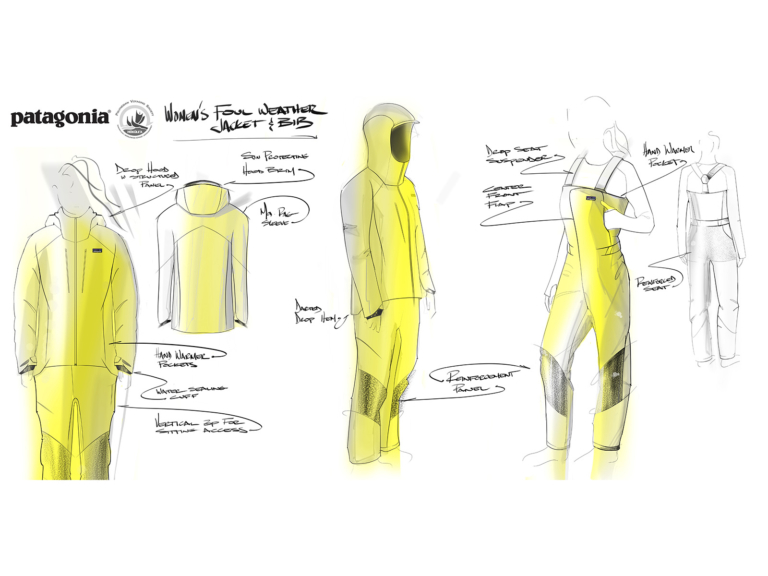

Sketches of the Women’s Big Water Foul Weather kit.

Big Water Foul Weather Kit

A prime example of our collaborative design ethos, the Big Water Foul Weather kit was created specifically for the Polynesian Voyaging Society’s Hōkūleʻa crew.

The conversation started when our designers from the Forge, Patagonia’s research and development facility, met with some crew members from the Polynesian Voyaging Society and discussed the group’s unique needs for their boat. The designers took a tour of the Hikianalia, the sister boat to the Hōkūleʻa, which was docked nearby in Oxnard, California, and evaluated the ways each person would move or be positioned and what activities were done in each part of the boat. According to the designer on the project, this meeting led to crucial information about key features, like the hood and pockets, and the ways in which water management would need to be addressed. The kit needed to keep water out, but also let out water that would inevitably get in.

The design takes into account a few essential factors, including the abrasion caused by salt water, the fact that the Hōkūleʻa crew sails barefoot and the need to be seen in low-visibility, stormy conditions. The bibs draw from our fly-fishing waders, and the shell incorporates elements of our alpine jackets, plus the need to withstand high-impact use. We’ve also added details like reflective strips, drain points and tethers for securing gear, which is essential on an open deck.

Clare Gallagher and Luke Nelson test a new kind of jacket in some challenging weather in Switzerland. Photo: Dan Patitucci

Just a 5,906-foot descent to go, and it’s only getting warmer. Clare and Luke ditch layers after crossing the Schöllijoch and Schölligletscher in Switzerland. Photo: Dan Patitucci

Clare demonstrates proper matador flair when retrieving an extra layer as she reaches higher ground and encounters some unexpected summer snow. Via Valais, Switzerland. Photo: Dan Patitucci

The High Endurance Kit

We knew that the line between running and scrambling was getting blurry for many athletes. We found that trail runners were spending long periods of time above treeline, sometimes using all four limbs, and were often transitioning from hot to cold to windy over the course of an entire day—the kind where you don’t even tick off that many miles.

With a few of our ambassadors, we designed a kit based on a series of questions and answers. There’s a rain jacket that can fit over a pack and includes zippers so you can access food and water underneath—because it’s hard to remember to eat and drink when all of your provisions are under a layer that’s keeping you dry. We created lightweight pants that fit over shorts and shoes for quick transitions on windy ridgelines and a pack that moves more like a piece of clothing than gear. And we designed a lightweight wind shirt with a hood and long sleeves that can double as a hat and gloves. The point was to make a self-sufficient kit specifically for mountain running.

Kohl Christensen outruns a giant. The morning started off a little slow during the high tide, but after a few hours it started pulsing, with the largest wave of the day around 45 feet on the face. Mavericks, California. December 20, 2014. Photo: Fred Pompermayer

Research and Product Developer Andrew Reinhart (center) tests a prototype of Patagonia’s PSI vest on Kohl (left), while Field Testing Manager Walker Ferguson (right) takes notes. Photo: Rusty Russell

The PSI vest under a wetsuit. Photo: Jean Louis de Heeckeren

Andrew and Walker assemble and check the hardware on PSI vests. Photo: Tim Davis

Greg Long and Paige Alms in Baja California, Mexico. Photo: Arenui Frapwell

Léa Brassy holding steady, drawing off the bottom of the beast. Chile. Photo: Jean Louis de Heeckeren

Kohl looks out at Waimea Bay, Hawai‘i, during the 2023 Eddie Aikau Big Wave Invitational. Photo: Ryan “Chachi” Craig

PSI Vest

Our Personal Surf Inflation (PSI) vest project started in 2011 after Kohl Christensen had a famously bad wipe out at Mavericks and the death of surfer Sion Milosky. What came next was a six-year design and testing process involving over 600 big-wave testers from around the world. The goal was to create a product that might make big-wave surfing a little bit safer.

Divers and free divers had used personal inflatables as a safety backup for decades, but the technology wasn’t really discussed as an option for surfers until recently. But after a series of close calls among surfers with the proficiency and ocean knowledge to be out in most conditions, our team started working on an inflatable solution. Taking cues from marine apparel and ocean-safety products for the military, the vest, in essence, is designed to get you to the surface as quickly as possible.

Andrew Reinhart, who worked on the project, called it “the largest collaboration between an athlete group and product design at Patagonia, if not the entire surf industry.” And the inflatable vest is now a core piece of big-wave surf safety. We own the patent, but because big-wave safety is something we care deeply about, in 2017, we also gave the technology away. The proceeds from the patent licensing were donated to the protection of the Chilean surf break Punta de Lobos.

Kohl and a few friends also started the Big Wave Risk Assessment Group (BWRAG), which teaches courses on ocean-risk management.

Vince Anderson kneels on the 26,600-foot summit of Nanga Parbat in the Himalaya, the world’s ninth highest mountain. Climbing partner Steve House’s mitten and ice axe are on the right. The other items in the rocks—the picket, rope and flag—are trash left by previous expeditions. September 6, 2005. Photo: Steve House

Two peas in a pod. Anne Gilbert Chase and Kelly Cordes test out a new alpine kit in Scotland. Photo: Jason Thompson

“Although this perch looks dramatic with the hanging daggers and a huge swell of ice overhead, this bivouac under the first ice roof is actually welcome horizontal terrain,” says Josh Wharton. “With a little chopping, we were able to have a comfortable night’s sleep and were safely protected from any debris falling from above.” Jirishanca, Peru. Photo: Josh Wharton

When Josh Wharton and Vince Anderson were climbing Jirishanca in 2022, by chance, Canadian climbers Alik Berg and Quentin Roberts were also on the east side of the mountain. “We hadn’t coordinated our climbing efforts, so you can imagine my surprise when Alik popped up over the ridge a few minutes after me!” Josh explains. “Jirishanca hadn’t been summited in 20 years. It would have been an amazing coincidence if they had arrived within an hour of us; for both teams to summit within five minutes of each other felt truly wild.” Photo: Drew Smith

The Doubles Sleeping Bag (aka the Spooner Sack)

This one never made it to market, but it is still in circulation among our alpine ambassadors. The first prototype of the Doubles Sleeping Bag, or “Spooner Sack,” was allegedly (and I say allegedly because the origin is a bit of myth) built at headquarters in 2005 and taken on Vince Anderson and Steve House’s successful ascent of Nanga Parbat in the Himalaya. The idea was an ultralight sleeping solution that might work as a more refined version of an alpine duvet. Josh Wharton first dreamed up his version of the idea in 2010, while making his first ascent of the Wave Effect on Cerro Fitz Roy. At the time, Josh and crew had one Black Diamond Firstlight and one sleeping bag for three men. As Josh puts it, they spent four nights wrestling over who would get the bag, and it was always a win to be in the middle. They shivered and talked about what a bag might look like that matched the weight and packability of a single sleeping bag, but would be warmer and, potentially, even more comfortable.

The process of constructing the Doubles Sleeping Bag involved a lot of tinkering, which Josh and Vince Anderson loved. One example, on a winter trip in the Black, they found out that the down quickly became wet with three people packed in a tent, so they added synthetic insulation panels along the sides of the Spooner.

Multiday alpine ascents are not exactly popular pursuits, but for the few that do them, a true technical Spooner Bag is kind of the dream. As Vince describes it, for climbs with three people and reasonable tent bivys, this kind of bag can save essential weight and space while adding a lot of warmth. Josh and Vince used it on both their 2018 and 2019 Jirishanca, Peru, attempts (they successfully climbed the peak in 2022), and Vince has used it a fair bit on peaks in Alaska. “I think there is no way in hell that Steve [House] and I would’ve gotten up Nanga Parbat in ’05 had we each taken separate bags,” says Vince. “As it was, our packs were 16 kilograms [35 pounds] each for our eight-day climb, and it was hard enough. The added warmth in a Spooner Bag helps reduce the needed insulation, so having separate bags would have easily added another 2 to 3 kilograms [4.4 to 6.6 pounds] to our load (the bag we used weighed 2 kilograms [4.4 pounds] total). I could go on and on about how it impacted that climb, but suffice it to say, it was crucial.”

Expedition Sewing Kit

The original Expedition Sewing Kit, known as the Diamond C, was sold in the old Chouinard Equipment catalogs as an essential tool for repairing clothes and gear when far away from home. It came in a leather pouch and included the standard sewing kit items (needle, thread, etc.) as well as a collet chuck (used to hold a tool in place) and cotter pin, which could be combined to form an awl. The cotter pin could also be used individually to replace a drawstring. After a series of requests from the ambassador team, one of our designers worked on a reissue of the kit a few years ago. The biggest shift was to improve the awl, which is now made of aircraft aluminum and can be handled with gloves on. The kit is also, it turns out, quite popular with Preppers.