Life Lived Wild

Editor’s Note: At the beginning of his memoir Life Lived Wild: Adventures at the Edge of the Map, Rick Ridgeway tells us that if you add up all his many expeditions, he’s spent over five years of his life sleeping in tents: “And most of that in small tents pitched in the world’s most remote regions.” It’s not a boast so much as an explanation. Whether at elevation or raising a family back at sea level, those years taught him, he writes, “to distinguish matters of consequence from matters of inconsequence.” He leaves it to his readers, though, to do the final sort of which is which. And in telling the stories of 26 expeditions across 16 countries, Rick also describes his gradual shift from someone fascinated by wild places to someone dedicated to saving them.

The following is an excerpt from Life Lived Wild, published by Patagonia in 2021.

With the tents up, we made dinner. The sun dropped below the ridge, and we put on our parkas and pulled on our watch caps. In this alpine zone there was no wood for a fire, but nevertheless we stood around our small stoves as though they offered heat, and while we ate, we decided it would be useful, for our own reference, to name the surrounding peaks, still illuminated in the light of day’s end. We christened the one we would try to climb the next day, naming it Explorer Peak. If that climb went okay, we might have a go at Rolex Peak, or Mount Oyster Perpetual.

The next morning, we left camp after first light and in an hour reached the toe of the glacier. It was smooth and steep, and Yvon swung his ax into the ice and the pick resounded with a high-pitched Thaaangg.

“Styrofoam!” he said with a grin.

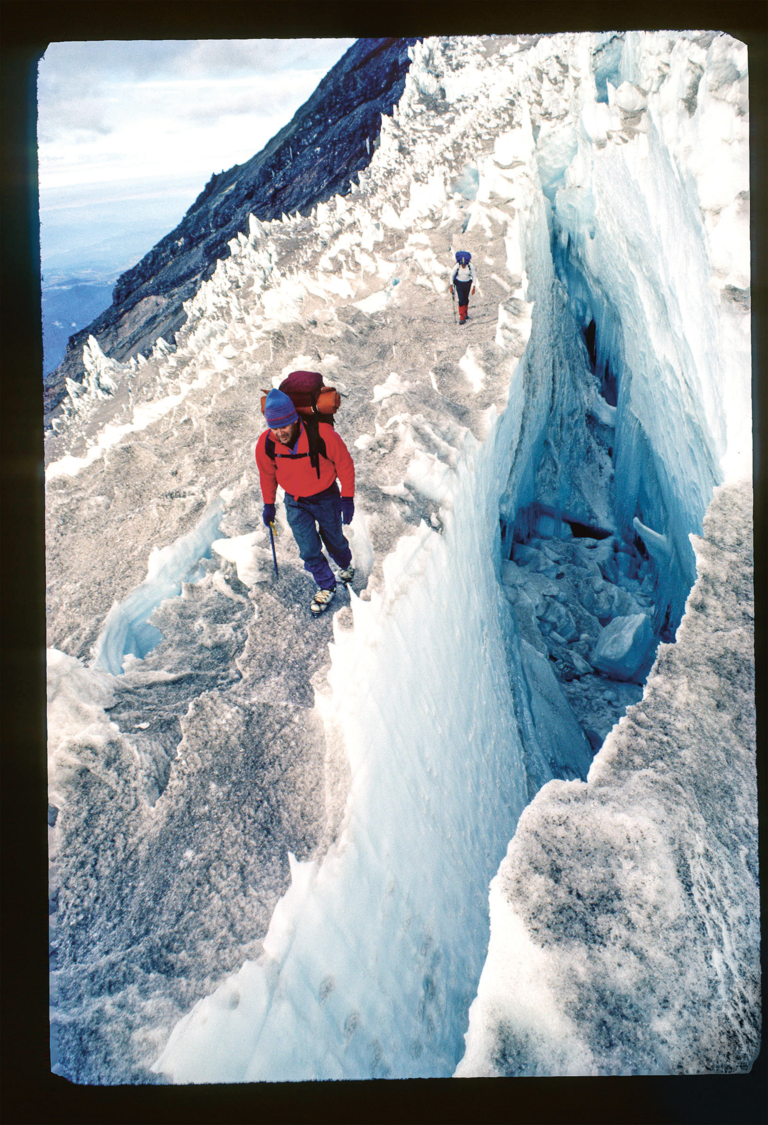

Tom Brokaw skirts a crevasse on Mount Rainier’s Kautz Glacier during his first snow and ice climb. Mount Rainier National Park, Washington. Photo: Rick Ridgeway

I knew that meant the ice was perfect: not so hard to make ax and crampon placements difficult, but not so soft that the placements might pull out. We sat and strapped on crampons. There were four of us: Doug and Yvon would be one rope team, and Phil and I would be on the second rope. The others had gone off to explore the cirque, and perhaps try another climb. With his crampons secured, Yvon shouldered his pack. His rope was still in it. He started to climb the steep ice slope, and Doug followed, a few feet off to the side, to stay out of Yvon’s fall line.

“Aren’t we going to rope up?” Phil asked.

“I’ll free solo with those guys,” I said, “and trail our rope. Then belay you up.”

I knew Yvon had judged the ice to be so perfect that, even though it was steep, there was no need to rope up. I knew Phil wasn’t nearly as experienced climbing ice, and I knew I also wanted to experience the gratifying tension when you climb without rope or belay, when you have no choice but to climb with irreducible focus.

Following Doug, I climbed off to the side of both of them in the possibility—even as it seemed an impossibility—that one of the Do Boys might make a mistake. But I wasn’t thinking of that because I wasn’t thinking of anything. I was in the zone where movement absorbs thought.

When the length of rope I trailed reached its end, I belayed Phil as he climbed. Once on the glacier proper, all of us roped up as there could be hidden crevasses; it was a risk that required management. When we reached the ridge of the cirque, we opened our parkas to cool our bodies and sat on our packs and ate candy bars. Looking above, the ridge was sharper than it had looked from the base. We continued, skirting cornices, balancing on knife-edges, ascending carefully up snow-covered rock. On the summit there was only room for two at a time. Doug and Yvon took the first turn, waving to me as I took a photo of them. They descended and waited while Phil and I took our turn, arms out for balance as we stood on the diminutive pinnacle.

(Left to right) Doug Tompkins, Rick Ridgeway and Yvon Chouinard on the summit of a previously unclimbed and unnamed peak in 2008, in what was still the future Patagonia National Park, in southern Chile. At first, they christened the peak Cerro Geezer, but Doug later had the Chilean government name it Cerro Kristine to honor Kris Tompkins, the force behind the final creation of the park. Photo: Jimmy Chin

We spent one more day “exploring.” John and Doug climbed Rolex Peak. The rest of us climbed to the eastern ridge of the cirque, reaching the glaciated crest by midday. We could see eastward along Bhutan’s border with China, toward India’s isolated Arunachal Pradesh, and northward into Tibet, a panorama dominated by Kula Kangri, a massive unclimbed 25,000-foot mountain that was part of a border dispute. It added to our sense of adventure that we were gazing across territory so remote no one was sure who owned it.

One of my teammates took the time to sight the compass directions of the peaks and to get altitude readings from all the high points. He drafted maps of our cirque, scribing the ridgelines, noting the summits, and using his altimeter to calculate rough elevations.

“Maybe you should draw dragons in the margins,” I said.

“Dragons?”

“You know, in the Middle Ages, when cartographers got to the edge of the map where the rest of the world was unknown, they used to write, ‘Here Be Dragons.’”

“Kind of appropriate, since we’re in the Land of the Thunder Dragon,” Yvon added, referring to the traditional name for Bhutan.

Back in camp, the yaks and yak herders had arrived. The expedition was over, and despite not being able to find our mountain, things had worked out. As we packed our gear, Yvon said there was one thing that was bothering him.

“The maps,” he said.

“The maps?”

“I don’t think we should publish them.”

“Why not?”

“The same reason I stopped reporting the new climbs I do in the Tetons. So the next guys who come along have to figure it out. So they’ll have the same sense of discovery.”

“That makes sense. But what should we do with the maps?”

“Burn ’em.”

“Burn ’em?”

“Yeah, torch the mothers. It’ll be the perfect ending to our trip.”

You know you’re off the edge of the map if you burn the map. Photo: Rick Ridgeway

Yvon Chouinard, the iconoclast. It took a moment for all of us to think it through, but soon we were into the idea. My teammate pulled out the maps he had so carefully drawn, and with his BIC lighter set them on fire. We stood around, cheering him on.

“Let there be dragons,” Yvon said.