Invasive Species: Reflections On How We Can’t Stop What We Started

This post comes from Patagoniac Kristin Jaeger, a PhD graduate student at Colorado State University who’s studying fluvial geomorphology. Kristin originally submitted this as an environmental essay for our catalog, but since it didn’t fit our current theme of Oceans as Wilderness we’re gladly presenting it here. If you have a story about invasive species please share it with us in the comments section.

Reflections on how we can’t stop what we started; the impacts of invasive exotic plants on the American Southwest

It’s not quite 7 a.m. and the mournful notes of a wooden flute descend from the canyon rim. I am sitting on the side of the dry streambed waiting for Dan to radio that his setup is ready and we can start surveying the stream transect. We only have a few hours before this particular study site turns into what I call the Sahara; our productivity plummets as the temperature rises and the summer sun turns everything blinding white. It’s July and I am in Canyon de Chelly National Monument located on the Navajo Reservation in the northeast corner of Arizona.

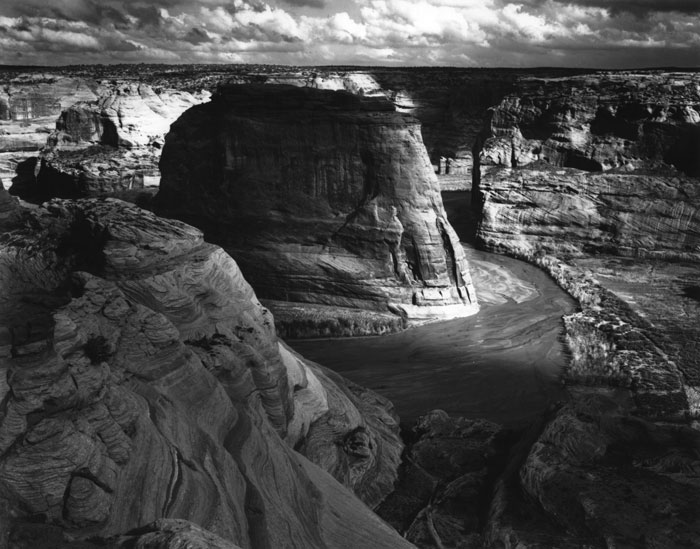

In 1942, Ansel Adams took a photograph from the canyon rim of where I am now sitting, near White House Ruins. The picture shows an open sandy wash extending more than 100 meters wide, a few cottonwood trees and beautiful, vertical canyon walls. Since that time and up until two years ago, the open canyon bottom became a dense thicket of tamarisk and Russian olive, both exotic, highly invasive plants that have become widespread throughout Canyon de Chelly and the American Southwest.

[Photos: Ansel Adams 1942 (left); D. Cooper 2005 (right)]

Throughout the American Southwest, cycles of stream channels incising, cutting deep into the erodible soils sometimes by more than 10 meters, and then infilling, have been documented. Many studies report that the streams started incising at the end of the 19th century and began infilling sometime after 1930. Reasons for this cut and fill cycle are hotly debated and include landuse activities such as grazing, streamflow regulation and exotic plant invasions, shifts in climatic regimes, or the idea that the cycles are intrinsic to the landscape and occur regardless of an external force. The channels in Canyon de Chelly have become narrower and deeper. But it is not clear if this is the beginning of a cut and fill cycle initiated by the plants, though it is clear that they exacerbate the channel narrowing and subsequent deepening.

The plants, originating in Asia and Eastern Europe, were first planted to stabilize the sandy, erodible soils of the southwest. Their population has exploded since the early plantings in the 1930’s. And now, because they are so effective at stabilizing bare soil once they have become established, they are charged with irreversibly converting wide open canyonbottom stream beds into narrow, incised channels and potentially lowering the water table. As a result, the canyonbottoms become drier and can no longer support the riparian plants, such as cottonwood and willow, which used to grow there. In Canyon de Chelly, the stream that had once been shallow and wide has become narrow with banks more than 4 meters high. Last year, a Navajo work crew with the use of a back hoe tore up the plants and burned them, leaving open, bare sand and the entrenched stream channel running through it. My job is to track how the stream will respond to the removal of the plants. Hence the transects, which cut across the channel where I measure the topography of the banks and streambed and determine if it has become deeper or wider or both.

After three years of working on this project, I can only now articulate the questions, though I remain unclear as to the answers. The Navajo have been cheerfully accommodating to this Belagona outsider who trespasses daily in this sacred landscape. I ask a Navajo grandmother who is out tending to her sheep in the canyon what she thinks of the plants being removed. I am consoled when her grandson, who serves as interpreter, tells me that it is good to finally see from canyon wall to canyon wall again. But my consolation ends when they ask me if this will bring back the water which they remembered flowed more frequently and which they used to farm the canyon bottom. Two years of data collection show that where the plants have been removed, the stream banks are unstable enough so that they widen, and sand from upstream sources deposits on the streambed making it shallower. However, our level of detection, in centimeters, pales in comparison to the several meter high stream banks. We have a long way to go.

I am glad that they can see the canyon wall now, which is marked by the artwork of the ancient people who came before them as well as their own Navajo ancestors. But I am not convinced that this stream channel is going to go back to what the grandmothers remember; to what Ansel Adams photographed. I fear the channel is so deep, the banks so high, that the stream is now stuck, entrenched. But only time can tell what will happen. I hope in ten years, I can return to this place and measure meters of change. I hope even more that the direction of this change is in the favor of the Navajo, that they will have the water they remember to farm their land. The only thing I am certain of is that through our own fault, these pervasive plants are here to stay in this southwest landscape. And we must continue to manage our way through the changes they inflict on it.

Dan radios that he is ready to start. I delay a half a minute and listen for the flute, but the player has stopped and likely moved onto the next part of his day. I heave myself up from the bank and start mine too.

For more information on invasive species, visit Invasive.org or the National Invasive Species Information Center. There’s also a standing call to action from the Union of Concerned Scientists. If you would like to support one of our environmental grantees, consider a donation to the Center for Native Ecosystems. And if you if enjoy fly fishing, learn how to prevent the spread of aquatic hitchhikers.

[Many thanks to Kristen for this story; good luck with the rest of your research. Ansel Adams photograph courtesy of The National Archives. Apologies to everyone for inadvertently posting this story before it was finished.]