In Solidarity with the Future

Even when the demands of a protest are not met, it can have lasting, immeasurable consequences.

All photos by Nina Riggio

Residents of a village called Lützerath were recently forced out so that it could be destroyed. A dozen other towns before it had died so profoundly that the very ground they stood on was dug up until no farmland, no fields, no trees, no roads, no homes, no barns, no trace of the centuries of rural life remained. Roads were rerouted so that the hole could continue to grow. Cemeteries were dug up, and their dead reburied elsewhere. In 2018, on a site where people had worshipped for a thousand years, a church dedicated to the saint Lambertus was smashed to make way for the ravenous devouring of the landscape.

Activists connected each of the platforms by ropes not only for stability but also to slow police. If one or more of the poles were chopped, it’d bring the others with it, leading to injuries and lawsuits.

To avoid being fingerprinted by police, activists in Lützerath pricked their fingers with pins, sealed the wounds with superglue and then hit the glue with glitter. Unlike California, where prosecutors must file charges within 48 hours of an arrest, authorities in Germany can jail activists for a week—aka “seven days of Giza”—before filing charges. The glitter needs to stick.

There are recent videos of the estimated 30,000 climate activists in Lützerath who, in January, put their bodies in the way of the machines eating a hole several miles wide. Climbers and classical musicians showed up, as did well-known public figures such as Greta Thunberg—while many longer-term occupiers were so eager to be anonymous that they went by creative pseudonyms. About a thousand dedicated souls occupied the village for years, building their own structures to inhabit and to blockade. Hundreds of scientists spoke up from afar to say this proposed mine was completely unnecessary for “energy security.”

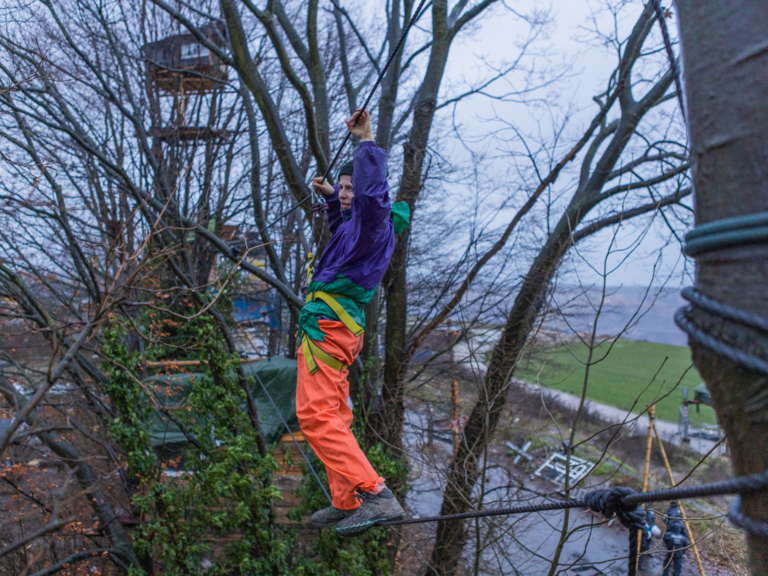

In talking about climate activism, we often talk about networks, and in this place, the networks were literal. The kind of tripods and cables used for tree-sits and other activism became a complex cobweb of wiring that allowed activists three-dimensional travel through the landscape and some very creative blockading tactics, as well as travel and residence out of reach of the police. This is not what Michelle Obama was thinking of when she famously said, “When they go low, we go high,” but climbers were key parts of the protest, and they went up tripods, across wires, up poles and to rope-slung platforms and treehouses, as well as engaged in lockdowns.

In mid-January 2023, the “tree-sit” climate activists had plenty of company. An estimated 30,000 lined up along the lip of the mine to oppose its expansion, as a reminder of a cleaner energy source loomed behind.

Among the many photographs taken is one that shows protestors standing on the lip of the vast hole, which will eventually fill with water and become an unnatural lake for who knows how long. Facing them is a huge earth-eating machine, a toothed wheel like a chainsaw for tearing up the land itself. If you believe in the future, it’s hard not to imagine that someone in the distant future will look at this artificial lake and wonder about the moment when gouging it out was briefly profitable for someone.

This is one way to describe the long expansion of a gargantuan coal mine in Germany, just west of Dusseldorf, that has been devouring farmland and rural communities for four decades. It now covers, or rather has uncovered, almost 20 square kilometers (around 12 miles). The protests oppose the destruction of the land and communities as well as the extraction of the coal, whose burning will contribute to climate change and undermine Germany’s commitment to transition away from fossil fuels and meet the Paris Agreement’s goals.

Activists go high to prepare for a day of arrests. By law, if you’re a few meters off the ground in Germany, the police must remove you one by one using a cherry picker.

It’s brown coal: lignite coal, the dirtiest, lowest grade version of the dirtiest fossil fuel, the foul stuff that no one—certainly not a wealthy country like Germany who has the resources to speed the transition to renewables—should be burning. The mine is described in a scientific article as one of the 425 fossil fuel projects worldwide with more than a gigaton of potential carbon emissions, aka the world’s carbon bombs. The hole in the ground is one problem. What’s dug out of it and burned is another even bigger one, the bomb itself.

The name of the mine is Garzweiler, after one of the devoured towns. Climate activists have occupied the trees, the abandoned houses, the fields and structures they built themselves around Lützerath since 2020 to try to stop the expansion of the mine. It is already so huge it’s easy to see on Google maps.

The view from the tree house where photographer Nina Riggio stayed, with Kante, a member of the protestor’s press team, in the foreground. As the police moved in, Kante made sure journalists knew why the activists had put their bodies on the line.

Without cellphones, the tree-house activists, such as Kante (pictured), commuted via ropes to visit one another and resupply. Pretty quickly you learned which tree house had the best food, the best toilet or one of the very few walkie-talkies for sharing. To remain anonymous, there were no cellphones allowed.

As with many other protests in recent memory, the passionate protests at Lützerath did not achieve their immediate declared goal. It would be easy and obvious to say, then, that they failed, that they accomplished nothing. But those summary judgments come from the expectation, demand or desire for direct and immediate consequences, and in that assumption lies so many kinds of trouble, a failure of vision and, I’d argue, the very root of the problem.

An activist tried to save a protest platform by moving out into the middle of the ropes. Impatient security personnel did not wait for a cherry picker this time and tried repeated to leap up and grab him, resulting in some unintended comedy.

Climate activists train to look right at press cameras and call out if they’re mistreated by police during arrests.

So many protests begin with a very specific demand. So often the demand is not met immediately—or at all. Yet these protests have other kinds of significant impact. Some of which can be measured, if you’re willing to look for indirect and delayed consequences, and some of which are, by their very nature, immeasurable.

Many years ago, a small group from one of the first organizations to protest the Vietnam War, Women Strike for Peace, politely protested at the White House. One of their number remembers how futile she felt, until years later when Dr. Benjamin Spock, the famous child-care advocate, became a powerful anti-war voice. He said that what drove him to act was seeing a small group of women standing in the rain on Pennsylvania Avenue years before. You cannot know the full consequences of your actions, and you must act in the absence of that knowledge. But you can know that emotions are contagious, and that living out your ideals and beliefs can instill hope and courage in others.

To pass the long hours in the damp and cold, a little guitar never hurts. Because the police and RWE security destroyed activists’ belongings, some sympathetic journalists and even state department people smuggled musical instruments and other valuables out on eviction day.

Acting on principle is like planting a seed. If you’ve planted the seed for a tree, it may take decades to bear fruit; a big tree like a redwood could take centuries to achieve its full size. We are still benefitting from direct as well as indirect consequences of many sowers long since gone, from civil disobedient and abolitionist Henry David Thoreau to Kenyan Green Belt Movement leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai. They planted; we harvest the fruits of their vision and commitment.

Of course, activism can achieve more immediate victories, if not always the ones it aimed for. The most powerful example I’ve seen of this in recent history was at Standing Rock in South Dakota in 2016, where a few Lakota women, and then more Lakota people, and then thousands of Indigenous and non-native people came together in an effort to stop a pipeline that would facilitate the shipping of crude oil and contribute to climate change. In doing so, the pipeline would violate the rights of the people of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, threatening the health of the river it would pass through directly upstream.

The pipeline was built. If you measure only direct consequences, the movement failed. But it also inspired hope, a sense of agency and power in the youth of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and many other Indigenous youth. It educated many non-native people about Indigenous history, rights and their violation, and about pipelines and their role in the fossil fuel industry. It created many cross-cultural alliances and friendships. It inspired Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—then an unknown young woman who had driven out from New York City with friends—to run for Congress, win and become a powerful voice for the climate.

Measuring only direct consequences is something I’ve often thought about in relation to activism; the stories above are stories I’ve told before to make the case for recognizing that so much of what matters may not be immediate or direct. But contemplating this recent conflict at Lützerath reminded me that we shouldn’t only measure protest in terms of the direct. We should do the same with what they’re protesting. If you account for indirect consequences, much exploitation of the natural world can be recognized as obscene and unprofitable. It’s true of the pipelines, the coal mines, the carbon that we continued to burn so recklessly after we knew what it meant for the climate.

An activist lays his body on the line to prevent the bulldozing of the surrounding trees.

The police cut a rope.

There’s a term for what corporations get, or rather what those who make and administer laws and regulations give to them: externalized costs. In other words, we make the activities they engage in profitable by awarding the profit to them and their shareholders and spreading the costs around. Often, they’re costs to locals, to the environment, to the climate and to the Earth, whether it’s extracting and burning fossil fuel, overfishing the seas, or exploiting workers, destroying soil and contaminating water in pursuit of industrial agriculture.

Often, the gains are short-term and the losses long-term, so timescale is another crucial factor in how you estimate value. Another word for externalized costs is selfishness: This is good for me; too bad it’s bad for you, and you, and you, and all you yet to come. And as the Guardian reported a dozen years ago, “the cost of pollution and other damage to the natural environment caused by the world’s biggest companies would wipe out more than one-third of their profits if they were held financially accountable.”

If you measure the dire impact on the climate of burning that low-grade coal, what’s being gouged out of the ground is not profit and security, but loss and ruin. If you count the loss of farmland that has been cultivated for many centuries, and if you look forward as long as the history of this place looks backward, you see that the short-term gain of some dirty fuel for the loss of land that could be farmed for millennia yet to come is bad economics.

Safety nets allowed for a greater number of activists to join the network of tree houses and platforms.

So protestors demanding that no coal mining take place are demanding something very specific and clear. But they are standing on principle, and that principle takes into account indirect consequences and externalized costs and long-term health, of seeing the big picture and not only the small. It’s a principle of connectedness, of indivisibility, of solidarity with all life, with the deep future, with the rights of people in the Global South not to suffer more from the consequences of climate change created largely in the Global North.

The night shift.

Environmental activists actively protest the expansion of Lignite coal mine in Lützerath, Germany, on Tuesday, January 10, 2023.

These activists—the people putting their bodies on the line on-site, their supporters around Germany and the world—are part of a global movement. It’s a movement to value the Earth and life more than privatized profit, deep time more than quarterly returns; and it’s one that is growing in strength, diversity, sophistication and impact. To see them fortifies my own commitment and clarifies my own understanding. I believe I am far from alone. What transpired in Lützerath earlier this year planted seeds. Let us look for them, water them and plant more of them—a garden of possibilities might spring up from the valiant work of climate activism.

On January 11, a special “climbing unit” of police carried off many of the tree-house activists.