In Haida Gwaii

I’d been dreaming about Haida Gwaii for as long as I could remember. Or, if not quite as long as I could remember, at least since my time as a skinny, bespectacled kid in public school, staring wide-eyed at the Haida totems in front of the Royal British Columbia Museum. In more recent years, with the spectacles gone, I’d been captivated by John Valliant’s book The Golden Spruce and Michael Nicoll Yahgulanass’s Haida manga, and I’d spent hours looking at photos of a perfect, sand-bottom point that some friends of mine had scored on a fishing and hunting trip. It had taken a long time to get to a place that figured so prominently in my imagination, so I couldn’t keep a grin from spreading across my face as I looked out from the window and realized I was almost there.

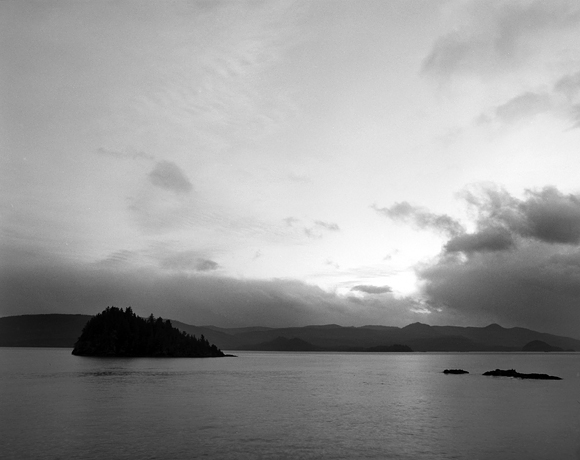

It had been just after sunrise when I climbed onto a Pacific Coastal flight that morning, pulling a toque over my ears to cut the propeller noise as the familiar shapes of the South Island slipped away. A few hours later, somewhere above the reefs and inlets of the Central Coast, I got my first glimpse of the archipelago formerly known as the Queen Charlotte Islands—off in the faintest distance, the high mountains of Gwaii Haanas appearing as a broken blue line above the horizon to the west.

Before long we’d bounced onto the ground at the Masset airport, and I was walking out into the freezing air with a pair of boards under my arm and crystals of frost crackling under my feet. I’d been invited up in the heart of the storm season for the Haida Gwaii Expression Session—a community surf festival organized by Michael McQuade, a stoked and stubbly Masset local whose backyard is home to the area’s only surf shop. My soon-to-be-friends Joe Curren and Eli Andersen had arrived the day before, and after half a day of travel I couldn’t wait to find them and get in the water—the surest way, on a surf trip at least, to make it feel like you’ve really arrived.

Totem pole at Old Masset. Photo: Joe Curren

Eli in Old Masset. Photo: Joe Curren

Traditional cedar canoes at Kaay Llnagaay. Photo: Joe Curren

The town of Masset—population 1,000, and probably the only town in the world that welcomes you with a carved wooden thumbs-up—is a sleepy place in the winter, so it didn’t take long to find Joe and Eli, load our gear into Michael’s camper, and set out to check the surf. Mighty Mike, as we’d soon be calling him, had checked the buoys and seemed sure we were going to score, so as we left the pavement and rolled through the rainforest that lines the beach, my mind started drifting back to dreams of head-high waves peeling off that perfect Haida Gwaii point.

Separated from the British Columbian mainland by the stormy waters of Hecate Strait, the hundred-and-something islands of Haida Gwaii have remained, in a number of ways, a world to themselves. Encompassing much of the traditional territory of the Haida Nation, the archipelago has an area of 10,000 square kilometres and a human population of only 5,000, and its location and history have made it a singular place in both the cultural and environmental senses. For surfers, there’s also the tempting fact that with hundreds of kilometres of swell-exposed coastline and only a small surf community, it seems, at first glance, to be one of the few places in North America where you can still find good waves to yourself. Like most of the Canadian West Coast, though, the possibilities are tempered by the realities of weather and access, and the islands are actually a surprisingly tricky place to find good surf.

Those realities sunk in fast as we drove out of the trees and onto the beach at that dreamed-of point, where we were greeted by perfect but painfully tiny waves curling along the sandbar, their energy flattening into nothing as they passed into the fresh water of the river. It was a bluebird day with light wind a solid swell, but for whatever reason the spot wasn’t working. We stayed on the beach for a few minutes, waiting for sets that didn’t come, before agreeing that we’d be better off going walking instead. My heart sank a bit, but it’s good to be reminded that you can’t hold on to your hopes too tightly, especially not on a surf trip.

Looking west from Tow Hill. Photo: Joe Curren

Looking east from Tow Hill. Photo: Joe Curren

Pulling on our jackets, we headed into the trees on a boardwalk trail that led to the top of Tow Hill, a sinister-looking basalt headland that loomed above the beach. Like many places in Haida Gwaii, it’s a piece of land that’s steeped in legend—in this case, the story of the crippled outcast, Hopi, who gets the girl by defeating the terrible monster Tow. We had an easier time climbing it than Hopi, though—no boulders being slung down toward us—and the view from the top made it well worth the walk, with wide-open sightlines over the long beaches and ruddy wetlands that stretch out toward Rose Spit. Out on the water, it was nothing but the great grey acres of the Pacific Ocean, marked only by gusts of wind and wide arcs of swell. Eli pointed out some spots he’d landed on his self-propelled circumnavigation of Graham Island, and the rest of us just leaned on the railing and looked out over this big, untrampled land. The sense was of total silence and total openness—Haida Gwaii is a place that hasn’t yet been deafened by the noise of the world, and many times in the next week I’d find myself closing my eyes and just sinking into the quiet.

After Joe shot some photos, we headed down and drove back to one of the beachbreak spots, eventually paddling out in the late afternoon with a few of the local crew. The surf was small but flawless, with Joe speeding along some rights on his fish and Eli sliding into a set or two on the 6’7” Ooligan he’d brought up. I lucked into a couple of fun ones, but mostly I was just trying to absorb it all—loving the clean, cold water and the feeling of being in a place where everything seemed that little bit sharper, that little bit more present and alive. From the water, I could make out the rounded shape of Prince of Wales Island across the border in Alaska—I was farther north than I’d ever been, and sometime in the midst of the session I realized that I was probably happier than I’d been in months.

Fun surf for the Expression Session. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

This kid was awesome. He acquired his board when it washed up on the beach. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

Joe and Eli, talking about waves. Or where to find some lunch. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

I stayed in Haida Gwaii for a week, and it became one of the fullest and most rewarding trips I’ve had in my own country—from feasting on smoked salmon and venison steaks at Danny Escott’s lodge to getting impromptu Haida language lessons from Jags Brown in Skidegate, and from hearing Eli’s story of how he earned the name Kaag’waal to spending an afternoon watching seals feed in the still waters of the Yakoun River. There were some great memories from the Expression Session as well—seeing local girls charging into beachbreak closeouts and come up laughing, sharing waves with some of the off-the-grid islanders, and getting a chance to slide a few peelers on a pearl-colored ’69 Jacobs log that has spent most of its life in this far-flung outpost of the Pacific Rim. Oh, and I met the keyboard player from Doug and the Slugs.

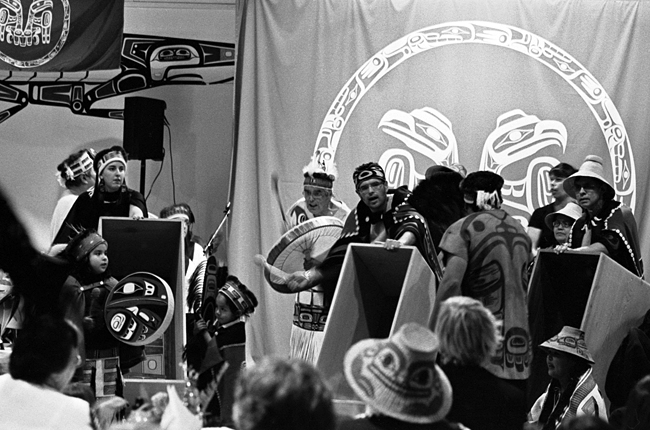

At the Athlii Gwaii celebration. Photo: Joe Curren

The most powerful moments, though, were throughout the evening in Skidegate that we spent at a celebration marking the 25th anniversary of the blockade at Athlii Gwaii, when dozens of Haida stood the line on a remote logging road to prevent clearcut harvesting in the southern half of the archipelago. The health of a people and the health of their land are tightly bound, and it hit right at my heart as the Haida elders spoke about how hard they’ve battled to save their culture and the islands that have cradled it for so many thousands of years. That night the community hall, the walls ordained in red-and-white Haida flags, was taken over by swirls and whorls of color—dancers in huge wooden masks, beautiful women snugged in ornate blankets, adolescent kids in spruce root hats and Miami Heat jerseys. At the end of the night, sated and happy after a communal dinner of soup, k’aaw and pie, we stood with hundreds of others as Guujaaw, the president of the Haida Nation, led the singing of the Coming Into the House Paddle Song:

“Yo ho wee, Yo ha wee yo wee yah, hey hi yo…”

As we walked out of the hall into the darkness that night, the words that were in my mind were the ones emblazoned on a big white banner at the celebration: Haw’aa, Haw’aa, Haw’aa. Thank you, thank you, thank you. There are places that, when you get there, don’t quite match up to your dreams, and there are others that, through their quiet beauty, make you realize that the world is more complex and more full of wonder than you could ever imagine. For me, Haida Gwaii will always be one of the latter.

Quiet. Photo: Joe Curren