It’s All Home Water: Oregon Steelhead

Feature: Squeaky Wheels, Wild Fish and Carrot Sticks

Editor’s Note: For a window into a day in the life of wild steelhead activist Jeff Hickman, check out our accompanying photo essay, Steelhead Green.

Oly Hickman is an excitable three-year-old. At the moment, he’s excited about the carrot sticks his mom, Kathryn, is doling out. He’s excited about doing laps around the kitchen. He’s excited by the new humans he’s just met—all of whom are talking loudly and at the same time. But most of all, Oly Hickman is excited to finally have the opportunity to goof around with his old man.

It’s been a long day for Oly’s dad, Jeff Hickman. Hickman is a prominent steelhead fishing guide, outfitter and activist for wild rivers and wild fish. Today at the office, a short coastal stream on Oregon’s north coast, sleet, snow, rain and even squalls of hail pounded down all damn day. There were two rafts to mother hen. Knots needed untangling and flies needed changing. A newbie required help learning to Spey cast. A pair of anglers somehow got lost in the woods—that was a new one. By the time Hickman beaches at the takeout, it’s dark. And cold. No steelhead. Not today. Maybe tomorrow.

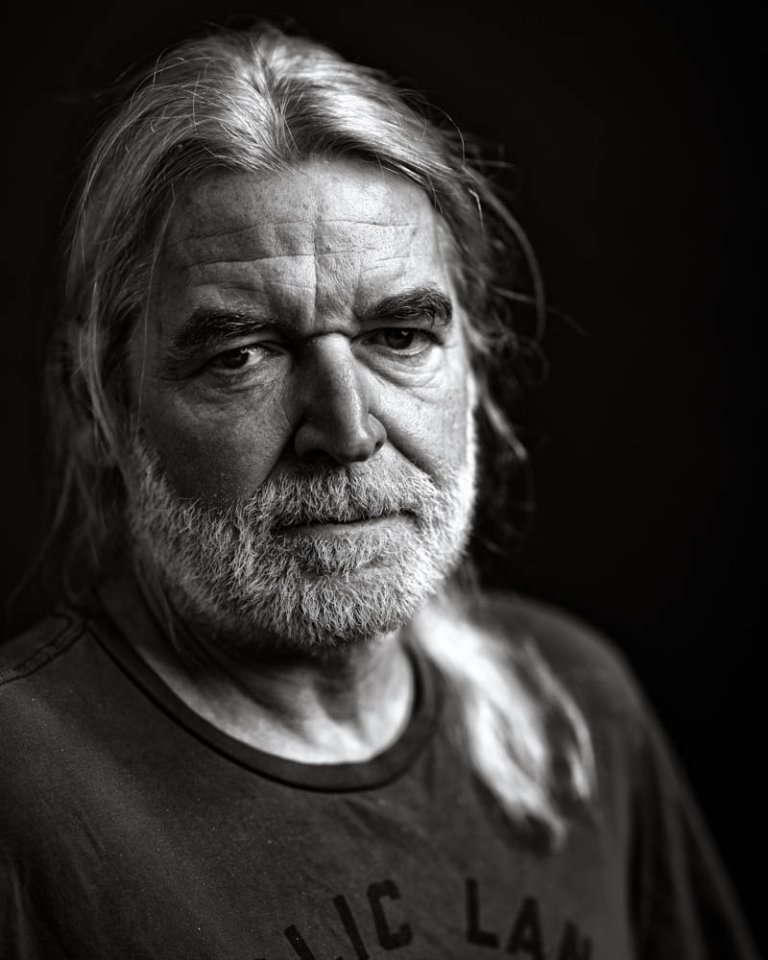

Nevertheless, Hickman is in a fine mood after the float, twirling a squealing Oly around his shoulders while he talks about river levels, weather and tomorrow’s odds. Hickman is central casting’s ideal steelhead guide. He is tall, rugged and hewn from sturdy stuff that resists wet, cold and wind. Given his size, reputation and occupation, one might expect Hickman to be a more imposing figure. Instead he’s disarming, earnest and enthusiastic—about everything. He finds small things funny and funny things hilarious, which is to say, he laughs a lot, a smile rumpling his permanent chin stubble and his chuckles rebounding off walls.

“I wouldn’t be able to sleep at night if I wasn’t active and vocal and doing what I can to make a difference.”

Oly logs a few more laps around the kitchen. A huge pot of pozole bubbles; crisping sourdough flavors the air; a salad attracts a few polite glances. The conversation drifts from the water’s perfect shade of steelhead green on today’s river to snow levels in the mountains to the latest local Sasquatch news. Everyone except Oly has a Bigfoot story.

Like his kid, Hickman is excitable, especially when talking about Bigfoot or steelhead or rivers— but especially steelhead and rivers. He waves his hands around, he gets louder and words come sprinting out of his mouth at a quicker pace. “Fly fishing is not only what I do for a living,” he says, “it’s my sanity.” But for Hickman, there’s something more than just the fishing that keeps him out late on a miserable Wednesday night. “It breeds stewardship … I feel like it’s my duty. I wouldn’t be able to sleep at night if I wasn’t active and vocal and doing what I can to make a difference.”

Hickman is a volunteer for the Native Fish Society, working as a river steward on Oregon’s Nehalem River for more than 11 years. In that time, the NFS has ended harmful dredge mining in over 20,000 miles of essential salmon habitats in Oregon, helped secure protections for 101,000 acres of public lands from strip mining in southwest Oregon and secured Scenic Waterway protections for the Nehalem River. Aside from showing up for meetings, hearings and planning sessions and marshalling volunteers for surveys and restoration projects, Hickman’s success as a wild fish activist is simple: combine the gift of gab with an insistently positive attitude. “The secret,” he explains, “is talking to your neighbor and getting to know people in your community—that’s grassroots activism.”

The second component to Hickman’s approach is to simply speak his mind, loudly if need be. “It’s a complaint-based system,” he says. “If you are complaining, you are going to make a difference. You’re going to influence change.” It sounds funny when he says it, and he can’t conceal a grin while saying it, but after the punchline, he presses his point. “This is not doom and gloom,” he says. “This is not me saying that the world is over, let’s all give up and get drunk. We’re at a tipping point and we all need to stand up and speak our minds and talk about what’s important to us. I think a complaint is worth a lot more than people give it credit for. The squeaky wheel gets the grease, man.”

On the river, Hickman’s natural intensity assumes another form. He seems remarkably at ease as he launches the raft, gears up and herds his day’s anglers as nonchalantly as if he were finishing up the evening dishes. With a fly rod in his hands, he is a wonder to watch. Standing knee deep in the flow, he commands his two-hander with motion that’s elegant and powerful, launching impossibly long, accurate casts across the full span of the river. He does it almost casually, barely stopping his steady stream of fish chatter. Hickman jokes, offers casting advice and reveals steelhead secrets that few people know. “Steelhead can be assholes,” he says. “Yeah, these fish are a pain in the ass. They’re super hard to catch. That’s not because they don’t bite, it’s because they’re not there. There’s not that many of them.”

Hickman need not even say it. It’s apparent in the clear-cuts, the logging trucks and the hatchery signs along these watersheds: the coastal rivers of northern Oregon and the steelhead that call them home are in serious peril. These fish, however, didn’t disappear on their own. They’re not on an extended vacation. Generations of abuse, neglect and greed have conspired to send entire populations into a death spiral. “Wild steelhead are struggling,” Hickman says between casts. “Their numbers are nowhere near where they should be.”

Those numbers are shocking. The best available data from historic and state sources strongly suggest a 90 percent ongoing decline in the Nehalem River wild steelhead population since the 1920s. Along the entire Oregon coast, agency data suggests wild steelhead in most rivers have been declining at a rate of 20-24 percent per decade since the 1980s. “If the average rate of decline continues,” says Dr. Chris Frissell, a fisheries biologist and Native Fish Society fellow, “it puts nearly all wild coastal steelhead populations at risk of extinction within 50 years.”

Nevertheless, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife considers populations like the Nehalem steelhead to be “healthy,” a graphic example of the tragedy of shifting baselines. Past information about run sizes is lost or forgotten, allowing steady, long-term declines to go unrecognized.

For Hickman, the decline of wild steelhead can be traced to two main culprits—logging and hatcheries. “The world has changed,” he says. “Everything is now about corporate greed.” That greed, he argues, is aided and abetted by Oregon’s state agencies. “Both the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Oregon Department of Forestry are departments of harvest. It’s the fox guarding the hen house. Both are run willy-nilly without any long-term solutions.”

Along the northern coast of Oregon, the logging industry is never far away. Photo: Jeremy Koreski

Driving down the coast, there can be no doubt, Oregon was and remains timber country, and the industry’s long shadow is everywhere. Along the U.S. 101 Highway, logs are stacked in enormous piles waiting to be shipped to Asia. The smell of mills fouls the air. Slash piles are heaped along the roadways and turnouts. Trucks heaving with fresh-cut logs rumble down muddy logging roads. Clear-cuts creep to within 60 feet of steelhead streams. Meanwhile, just a few miles away, tourists flock year-round to Cannon Beach, not for the slash piles to the north and south, but to gaze at Haystack Rock, hike Ecola State Park and enjoy a taste of the local beer, wine and seafood back in the charming town. The contrasts between the thriving, year-round recreation and tourism industries and the rampant destruction just up the timber roads are stark and lend a feeling of antiquated desperation to the mills and timber lots.

“Look,” Hickman says, “the environmentalists didn’t kill our jobs here. We’re cutting more trees now than we ever have and employing fewer people. It’s a fairy-tale legacy story of logging. Timber doesn’t benefit many people. Our schools are not better. We’re not really getting any revenue. Communities are not profiting from the timber sales; [they] are getting poisoned and the rivers are getting filled with sediment.”

Floating these rivers with Hickman, it’s hard to disagree. During downpours, water courses through the clear-cuts and over the hacked-up land, sluicing muddy run-off into the river. Hickman hops out of the boat and bushwhacks through the undergrowth. Within moments, he’s pointing to a slope where trees used to be. “The rate of timber harvest is alarming,” he says. “That impacts everything on this river—the water quality, a higher likelihood of slides, more extreme flooding.”

He points across a cleft in the land where a new stand of trees, a few years old, greens the slopes. Hickman talks about the aerial spraying of chemicals used to keep vegetation at bay while the monoculture crop of the Douglas fir matures. The chemicals include imazapyr, a weed killer; clopyralid, an herbicide; along with glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup; and 2,4-D, an ingredient in Agent Orange. Hickman wonders out loud about what those chemicals are doing to the river, the fish and his family’s drinking water. Next to the new stand of Doug fir, the rest of the slope has been freshly shorn—just stubble remains. “This is about responsible management of resources,” he says against a backdrop that seems anything but responsible. “I’m not the extremist here.”

Catching and releasing a wild steelhead is a moment to be celebrated. Everyone on the raft shares the accomplishment. Photo: Jeremy Koreski

In the raft, Hickman stands at the oars much of the time, guiding the boat through narrow channels and around rocks and standing waves. He eyes a likely-looking stretch downstream and slides the boat to the shore at the head of the run. He checks the fly, the leader, where he’s standing—the little things—and begins to unfurl those casually magnificent casts, talking all the while. He talks to the fish. He talks to himself. He tells everyone what he’s thinking and what he thinks the fish are thinking. Finally, it happens. A fish grabs his fly. The reel zings that zingy sound and the fish bolts. Hickman called the shot. The fish was exactly where he said it would be. He grunts, his long Spey rod bucks and curves into and out of a rainbow shape. Someone runs to get the net.

“Hatcheries have been around here for 150 years and we’re still in a fisheries crisis. If hatcheries were going to bail us out, they would have by now.”

After a few minutes, the battle is over and the fish flails in the mesh. It’s a hatchery steelhead, fins scraped and rounded by months of contact with concrete walls and raceways. The fish has violent red scrapes on its flank; Hickman hypothesizes it’s recently escaped an encounter with a hungry seal. The fish is smallish, ill-formed and didn’t put up much of a fight. It’s quickly dispatched with a piece of driftwood; the gills are slashed and its blood runs into the river. Hickman is still jacked from the grab, but is noticeably unimpressed. In fact, he’s a bit disappointed. “I don’t know why,” he says, “human nature thinks we can do something better than nature.”

Hard to catch, harder to hold. Jeff Hickman fumbles the release of a wild steelhead in northern Oregon. Photo: Jeremy Koreski

The fish is in the bottom of the boat turning from bright silver to pale grey. Hickman is back at the oars, his eyes on the bank searching for the next run and, hopefully, a wild fish. “I don’t dislike hatchery fish,” he says a bit unconvincingly, “I just want to see our fisheries survive long term and I see hatcheries as a very short-term Band-Aid on a long-term problem. Hatcheries have been around here for 150 years and we’re still in a fisheries crisis. If hatcheries were going to bail us out, they would have by now.”

Recently, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife began what’s called a broodstock hatchery program on the North Fork of the Nehalem River. In this scheme, wild fish pairs are harvested from the river and their eggs and milt are collected. The fertilized eggs are incubated, hatched and reared until they are released back into the stream. “Last winter the hatchery on the North Fork started recruiting native fish—broodstock—because their hatchery programs seemed to be collapsing. They just started collecting broodstock. There was no public input. There was no science. They don’t know what harvesting those fish will do to the run.”

The experiment didn’t go well. Fourteen spawning pairs of wild steelhead were harvested from the river, creating 42,000 smolts. Of those hatchery smolts, 30,000 were lost to Flavobacterium psychrophilum, an affliction suffered by hatchery-reared fish also known as Bacterial Cold-Water Disease. “You just have to leave ’em alone,” Hickman says, “If you leave them alone the wild fish will come back on their own. These are wild steelhead. They can do anything.”

After another long, gorgeous day on a short, scrappy coastal river, the mood in the kitchen is again warm and welcoming. There are beers flowing, the fish is being sliced into fillets and Oly is, once again, stoked to see his old man. After a few laps to release some excess energy, Hickman and his son settle down for a round of carrot sticks and juice. Unlike most kids, he shows no interest in the dead hatchery fish. Even at his age, he’s seen plenty. Hickman grabs his son and gives him a just-for-the-heck-of-it twirl around his shoulders. “We’re at a tipping point here,” he says. “It’s our responsibility to protect this for future generations—for my son and his kids. You know,” he pauses, “if we screw things up right now, it’s going to be forever.”

Help Revive Abundant Wild Steelhead

Tell the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife that you support Oregon coast wild steelhead and their future protection.