Ghosts

What We Fish for When We Fish for Carp

“When the buffalo are gone, we will hunt mice, for we are hunters and we want our freedom.”

—Chief Sitting Bull

Come early summer, Washington State’s Columbia Basin is a griddle. Heat wobbles everything, wind sandblasts the paint off abandoned farm equipment, red-tailed hawks ride upswelling thermals for hours, looking for something—anything—to rustle the sage. Despite the inhospitable nothingness, the smell of mint carries on the wind. There are apple stands along the melting two-lane roads. Trucks loaded with sugar beets regularly rumble past. Since 1948, the Columbia Basin Project has been siphoning what equates to the annual flow of the Colorado River from the once-mighty Columbia to slake the thirst of the vineyards, orchards and hop vines that paint what should be a dusty brown canvas in huge, green rectangles. Nothing fragile should grow here, but it does.

We plan trips to this desert only when it’s simply too damn hot to fly fish for trout a few miles away. After all, who wants to beat back Yakima Canyon rattlers, broil on a casting deck and toss flies to indifferent, sluggish rainbows when, instead, we could slog along the scorching Columbia, posthole through knee-high muck and cast to indifferent, skittish carp that may or may not even be there in the first place?

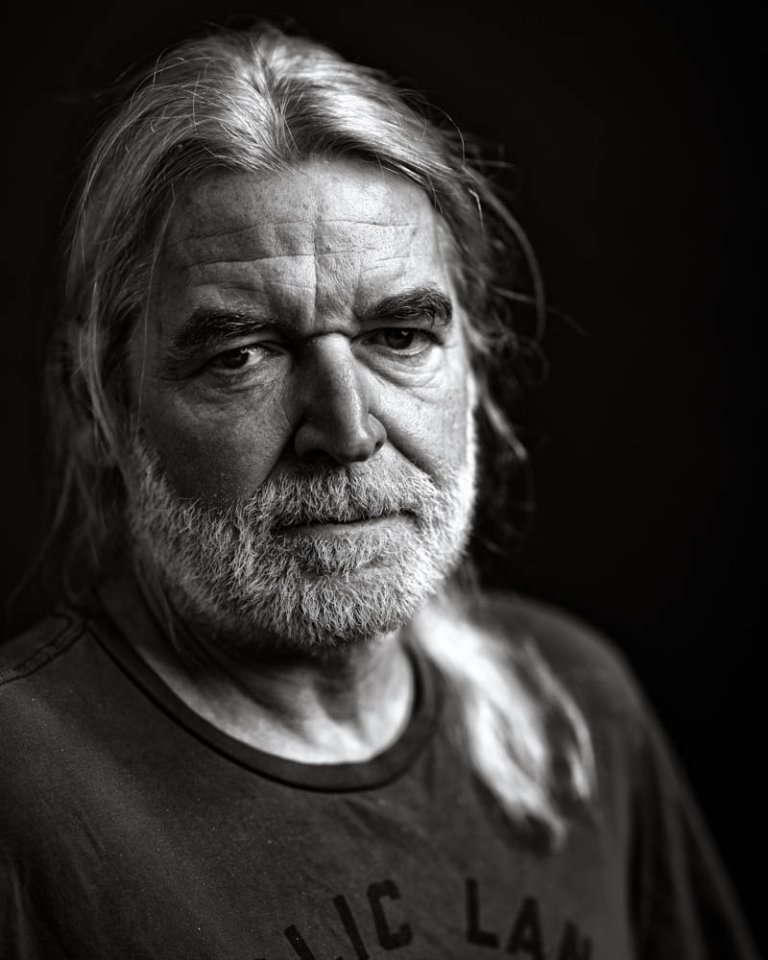

Gonna need a bigger net. Landon Mace scoops and scores on Washington State’s Columbia River. Photo: Arian Stevens

The Columbia, of course, was once host to history’s most prolific salmon runs. As the Lewis and Clark Expedition began its drift to the Pacific in the autumn of 1805, William Clark noted in his journals that “the rivers were crouded [sic] with salmon.” Indeed, “the number of dead salmon on the shores and floating in the river is incredible to say.” Ask any old-timer about the runs before the dams started going up, and you’ll hear the old chestnut about being able to promenade across the Columbia on the backs of the salmon and never soak your boots.

The sad collapse of this once-teeming abundance has been well documented. Careless environmental practices, overfishing, resource extraction and dams conspired to bully salmon populations into free fall. Our present spectral returns are a seasonal reminder of a shortsighted hubris as awe-inspiring as the vast, lonely spaces once dominated by this flow.

Today, we are left with Cyprinus carpio, the rather glumly designated common carp. The regret and hand-wringing trotted out for the Columbia’s ghost salmon is matched only by the contempt for their replacements. When the subject is raised, carp are usually on the receiving end of eradication programs, crossbows or quarter sticks of dynamite. Among fly anglers, however, there is love enough. The common carp has been recast as the fabled basalt bonefish, the wily and elusive Columbia River brownback, the rod-busting desert ditchpig.

Bob Stewart unleashes an absolute tanker. Large Columbia River basalt bones regularly top the 15-pound mark. Photo: Copi Vojta

Romans cultivated Cyprinus carpio as a food stock more than two millennia ago, and so it was that an anonymous Oregonian, in 1880, set himself up with a few dozen imported German carp, a handsome new spawning pond and lofty dreams of menus featuring carp caviar and thick carp steaks. These pioneering carp were hardly “common.” According to the surviving narrative, the vanguard that began the Columbia River population were “genuine German carp and perfect beauties.” Within a year, the brood had grown to more than 7,000 fish. That spring, disaster struck. A deluge breached the pond, sending the beauties finning into the Columbia. By the turn of the century, carp were being harvested in massive numbers as fertilizer for farmers. The cost: five bucks a ton.

A few years ago, fly fishing for carp was the hot new thing for about 20 minutes. Perhaps it was because of the hostility heaped upon them due to their homely looks and brutish ways that they became the antiheroes—the punk-rock bonefish—of the fly fishing world. The hype didn’t last. Anglers still search for them, but the truth is that carp can be as difficult to hook as permit; they ain’t all that easy to find and once hooked, well, then what?

Want to bust your favorite trout rod? Take it carp fishing on the Columbia River. An unidentified Columbia River goldenback tests the absolute limits of Gregory Fitz’s eight-weight. Photo: Copi Vojta

Every carp expedition begins with recon. But because carp anglers are so secretive, good information is always tough to come by. Dam release schedules are studied, water temps verified and a single, trusted contact residing near the flats is gently prodded for firsthand intel. Mostly, we go by our guts. Does the forecast call for hot, hotter, hot as hell? Will the winds be calm? Will the water be low enough to expose the stalking grounds?

Columbia River carp flourish in the wide spots between dams. What was once described by tumbling runs and broad, sweeping pools stuffed with salmon is today a featureless reservoir pinched between the United States Army’s live-fire Yakima Training Center on one side and row after row of apple trees and prefab housing on the other.

To get to the carp flats, skirt Washington State’s Ginkgo Petrified Forest along I-90, cross the Columbia at the Vantage Bridge and head south down the river’s eastern bank. Drive past the cherry stands near Beverly, the taco trucks at Mattawa and the wineries at the base of the Saddle Mountains until you see the post that formerly held the sign pointing to where the public fishing access used to be. Take a sharp right and skirt the destroyed single-track to the river. Shift into 4×4 and follow the trace near the bank. Park out of sight, in the shade. Drink some water and enjoy the last moment of the truck’s air-conditioned breeze.

Carp rush onto the river’s flats—broad expanses of clear, knee-high water that shelter and nourish vast underwater fields of clams—when the sun is high and the water is warm. The shells crunch underfoot as you walk across the flats to an exposed island 200 yards offshore. The bottom is riddled with pockmarks caused by the rooting snouts of big, hungry fish.

There are many theories when it comes to fly selection. Wooly buggers, pedestrian trout nymphs such as pheasant tails and hare’s ears, bonefish flies and crawfish patterns have all been known to work. Most carp anglers prefer self-styled creations—quick-sinking, nymph-shaped inventions with just enough movement (a whiff of rabbit tail, a shock of marabou) to catch the eye of a gorging carp.

The anglers wade deliberately across the flats. Everyone looks as if they are in slow motion, and their profiles shimmer in the unrelenting heat as they drift farther and farther apart. Carping is a sight-fishing activity and when one is spotted, the game has only just begun. If the carp is a cruiser, swimming with the targeted purposefulness of a deepwater submarine, forget it. Let it swim by. Cruisers don’t eat and eaters ain’t cruising. Spot one with his nose pressed to the riverbed, tail swishing the air and a small puff of mud around him, however, and well, maybe …

Are you close enough? Forty-foot casts just don’t cut it on the flats. You need to see the carp inhale the fly. Creep closer. Peel some line. Measure—not too many false casts. Place the fly. Yes. There it is.

A carp can suck up a fly from more than a foot away and a strike telegraphs a weighty, dull thump through the line. More than likely, the fly is lodged in the carp’s thick, rubbery lip. It’s not coming out until your tippet breaks, your rod snaps or you land the beast.

A carp’s first run is like a logging truck chugging down a steep grade. It’s not going that fast at first, but good luck getting it under control and forget about stopping it anytime soon. A heavy (12–15 lb.) basalt bone will run 100 yards before taking his first breather. Expect another handful of spirited efforts before surrender. Grab the carp with a BogaGrip. Remove the fly. Revive. Repeat.

Thanks to 11 dams in Washington State and Oregon, the Columbia River has been reduced to a series of broad, slow-moving, carp-filled lakes—a far cry from what once was the most prolific salmon habitat in the world. Photo: Arian Stevens

There are only a few hours of prime fishing. The winds inevitably whip down the canyon, chopping the water and conspiring with the glare of the declining sun to put an end to the day’s work.

Back at the truck, after a cold can of beer, the river’s ghosts—the salmon—are resurrected. What it must have been like way back when, before the dams. How big the runs must have been; how good the fishing surely was; how we’ve been cheated and deprived and robbed of our salmon. We’ll silently nod our heads and spit into the dirt as yet another description of the phantoms to which we are shackled drifts past our ears.

Of course, we’d rather be fishing for steelhead and salmon. Who wouldn’t? The point is, we aren’t. We can’t. No one home. No forwarding address. Only these haunting spirits—unavoidable, ever-present, contemptible. We are witness to a never-ending eulogy. We are left with the luxury of our indignation. We are left with Cyprinus carpio.

These are our ghosts, as much a measure of carping as the carp themselves.