Why Regenerative Organic Agriculture Is All About Farming Down

The promise of regenerative organic agriculture.

“The problem is that we’re all taught to farm up,” David Oien says, leading me into a field of low-growing plants that I will later learn to recognize as lentils. I try to think of what alternative there might be to farming upward. Outward? As I puzzle over this, he startles me. “Nodules!” he exclaims, pointing to a cluster of bulbous, reddish growths on the tip of a lentil root. He’s just finished hewing the plant from the earth with a spade. Now he’s grinning. The nodules form, he explains, when a type of bacteria called Rhizobium pulls nitrogen out of the atmosphere and sets up shop in the plant’s roots. This nitrogen fixation, he says, is one of the more miraculous collaborations in history: It provides lentils with their very own fertilizer.

A graduate student in geography at University of California, Berkeley, I had come back to my home state of Montana to learn about more sustainable approaches to agriculture. My journey had led me to Timeless Seeds, a farmer-owned lentil company on a mission to spread regenerative organic agriculture—the practice of growing food without chemicals by sustaining healthy soils. This research was personal. My grandmother had lost the family farm in the Dust Bowl, and I’d recently lost faith in mainstream agribusiness after a short-lived career traveling through rural America as a country singer. It probably sounds corny, but I had a strong hunch that regenerative agriculture was more or less the secret of life.

Just as I was about to ask what he meant by farming down, Dave volunteered an answer. Like most Montana farms, he said, the place where he grew up had been geared toward maximizing yields of just two cash crops: commodity wheat and barley. This narrow focus on annual wheat and barley yields had gradually shifted all the fertility of Dave’s soil upward—from the roots of the plants to their seedheads, which were exported off the farm and out of state. The short-term yields were good, but as soil fertility declined so did farm profits. So when Dave came back to the family farm in 1976, he reoriented the entire farm operation to focus on the health of the soil. That’s what he meant by “farming down.”

Timeless Seeds co-founder Dave Oien observes a lentil plant on Nick Mehmke’s field, one of dozens of family-owned organic farms in Big Sky Country that Oien’s business supports. Photo: Amy Kumler

Farming down is not new. As American agricultural scientist F.H. King learned a century ago on a research trip to Asia, farmers in China and Japan have been feeding their soils with mulch and soil-building crops for thousands of years. British botanist Sir Albert Howard learned much the same thing a couple decades later while stationed as an agricultural advisor in India. The farmers Howard was supposed to be teaching ended up teaching him instead, astounding him with the marvels of compost. Upon his return to England, Howard set about sharing this “Indore Process” for composting, inspiring early organic farmers in the United States and Europe.

In two widely influential books, Howard expounded upon what he called the “Law of Return”: For farming to be sustained, all nutrients removed from the soil had to somehow be put back in. Yet, just as King and Howard were learning these ancient secrets to sustained farming, agricultural chemists were refining a different approach: synthetic nitrogen fertilizer. Nitrogen, these chemists reasoned, was typically the limiting nutrient for plant growth, so why bother with a messy pile of compost when you could amend the soil chemically instead?

Nitrogen manufactured with fossil fuel dovetailed neatly with the rise of industrial farming in the United States and Europe. Its fortunes climbed yet higher after World War II, when wartime chemical factories found themselves in need of civilian purposes. New seeds for staple crops like wheat and corn were developed to be more responsive to this chemical fertilizer, and government extension agents were deployed to encourage farmers to apply it. By the 1960s and 1970s, U.S. scientists and farmers alike had all but forgotten Howard’s Law of Return. Monocultures of grain were harvested out of the soil each season, but nothing except chemical fertilizer was put back in. This put farmers on a treadmill, in need of ever more fossil-fuel-based fertilizer as they depleted the natural fertility of their soils. Facing a crash course with bankruptcy and climate change, vanguard organic farmers like Dave decided the only way to survive was to opt out of chemicals altogether.

These days, given the increasing frequency of extreme drought, it’s not just organic farmers who are looking to soil health to achieve greater resilience in a changing climate. Interest in cover cropping and regenerative grazing is spreading throughout Montana, as is lentil acreage, which has multiplied by a factor of 100 in the Big Sky Country since Dave co-founded Timeless Seeds in 1987. Meanwhile, farmers and ranchers are also beginning to learn that the carbon-rich organic matter that they value for soil health has another kind of value, which may be a new agricultural income stream: carbon sequestration.

Globally, soils store a lot of the carbon cycling in and around the earth—about three times more than the atmosphere. And, it’s not all locked up deep underground: In fact, the vast majority of the organic carbon is in the top meter of soil and is directly impacted by management. So far, this management-sensitive nature of soil carbon has mostly been bad news, as industrial farming practices have released large amounts of soil carbon into the atmosphere. But the good news is that this is one very significant component of climate change that appears to be well within our grasp.

Kibiwott, an agronomist, holds a handful of cleaned organic lentils at Timeless Seeds. Photo: Amy Kumler

When Dave and three friends founded Timeless, their goal was to create farming systems that could sustain themselves without chemical fertilizer and herbicide. Pretty quickly, the founding farmers figured out that monocultures of wheat and barley, the typical commodity crops in their area, weren’t going to cut it. They needed to diversify their rotations to add back in the nutrients these crops were removing from the soil. Looking around the world for inspiration, the Timeless founders observed that most traditional farming systems rotated grain crops with either livestock or legumes—plants in the bean and pea family that could work with bacteria to fix their own nitrogen. Recognizing the genius of this homegrown fertility strategy, the Timeless farmers immediately started planting legumes as soil-building crops, which helped boost their organic matter. But they also needed an income stream. So they found a harvestable bean adapted to arid, short-season farming: lentils.

By the time I met Dave 25 years later, the farmer-founded company had matured into a soil-to-fork business. Dave and his growing staff traveled all over the state, helping farmers learn how to grow organic lentils and rotate them with grains and cover crops to build their soil. At harvest time, Timeless purchased these lentils, cleaned them to food grade and marketed them to natural-food stores around the country. As Dave explained to me, some growers initially sought out Timeless for economic reasons. It was hard to make enough money selling commodity grain to pay for the costly chemicals and equipment required to grow it. But that wasn’t all. Many farmers were also concerned about cancer in their communities, and they worried about the impact of herbicides on their families’ health.

The summer I visited Dave and his growers happened to bring one of the worst droughts to hit grain country since the Dust Bowl. During one of our field visits, Dave showed me the shriveled barley at a neighboring farm, which he told me would likely be a total loss. I was surprised to see the dramatic difference in the Timeless growers’ barley, which was a little short but still looked quite healthy. Soil organic matter made the difference, Dave explained. A decade and a half of feeding the soil was paying off in the form of precious moisture stored belowground. I checked back in with Dave after harvest, curious how well his growers’ crops had held out. “Well, we only got about 40 percent of our typical moisture,” Dave told me, making a back-of-the-napkin estimate across the rain gauges of his dozen or so suppliers. Prepared to hear the worst, I nearly dropped my notebook when Dave finished his sentence. “But our growers still got about 80 percent of their typical yields.”

Photo: Amy Kumler

It ’s not just farmers who benefit from the climate-buffering effect of regenerative organic agriculture. Through carbon sequestration, this way of farming might be our best hope of softening the blow of climate change for our entire planet. Exactly how much carbon we could sequester through regenerative agriculture is hard to pin down. Soil ecosystems are complex and dynamic, and quantifying all the variables that contribute to stabilization or destabilization of carbon isn’t easy. For example, some scientists have pointed out that rising global temperatures may lead to more destabilization of soil carbon than previous estimates have predicted. Modeling the impact of human management is even trickier, as regenerative farming can involve such a diverse range of practices. Taking all this variability into account, a team of scientists from 17 countries recently published an estimate of how much carbon we might store through a global commitment to increase soil organic matter by just four-tenths of a percent. This “4 per mille” or “4 per 1,000” initiative, they found, could likely sequester enough carbon to offset 20 to 35 percent of greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity.

Even so, my experience with Dave and the Timeless growers cautioned me against getting too caught up in the search for the holy grail of quantifying soil carbon sequestration. It’s an important part of regenerative agriculture, these farmers taught me, but it’s not the whole enchilada. Don’t forget, they reminded me, that solve-for-one-variable thinking is what got agriculture into its degenerated state in the first place. What we need is not just a different variable to solve for—soil carbon sequestration as a substitute for nitrogen levels or crop yields—but a whole different way of approaching our relationship to farming and food. In jest, I proposed to Dave that perhaps we should be paraphrasing John F. Kennedy: Ask not what your soil can do for you, but what you can do for your soil. “You know,” he replied, “that’s not a bad mantra.”

“At Timeless, we think in terms of the whole farm system,” Dave explained to me as we finished up our field tour. “If our growers are using cover crops for fertility, that means they’re not using synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, which is a significant piece of agriculture’s greenhouse gas footprint. So yes, they’re storing carbon, but they’re also keeping us from generating so much in the first place.”

This, I’ve come to understand, is what regenerative agriculture means. It’s not just about storing carbon or fixing what we’ve broken. It’s also about giving back to that which gives us life. In this respect, regenerative organic farming is, at its root, a passionate argument that we humans can do better.

This essay was featured in the March 2019 Patagonia Catalog.

Regenerative Organic Agriculture

Dwight Eisenhower, World War II’s wizard of coordination and logistics, said, “Whenever I run into a problem I can’t solve, I always make it bigger. I can never solve it by trying to make it smaller, but if I make it big enough I can begin to see the outlines of a solution.”

Regenerative organic agriculture takes unimaginably unsolvable problems like global warming, freshwater loss and pollution, topsoil loss and degradation, factory farming, chronic rural poverty and the need to feed 11 billion people by the century’s end—and begins to reveal, and create, the beginning of a solution.

Organic agriculture has been one of humankind’s few gifts back to nature over the past 50 years. Keeping chemicals out of the soil creates more nutritious, better-tasting food and requires no synthetic nitrogen- based fertilizers that run off into rivers and create dead zones in fresh water and salt water. Organic agriculture requires no air-polluting and lung-damaging crop dusters, and kills no raptors or bees or monarch butterflies. The use of organic fertilizer improves soil health (as does compost, which also increases microbial biomass health to hasten nutrient cycling), suppresses disease and increases root growth, which helps take carbon out of the air where it does harm and sink it back into the soil where it grows food.

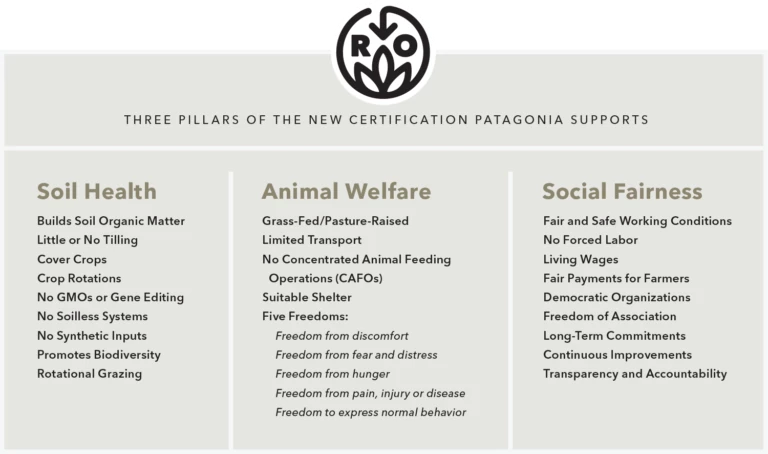

But it’s time to raise the organic standard to include regenerative practices for soil health that create a self-perpetuating living system on the farm, with less need for outside inputs like organic fertilizer and irrigated water, and that maximize the potential for carbon sequestration. That’s why Patagonia is getting behind a Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC). We recognize that we cannot attain the agriculture we need without seeing the problem whole. To address its root causes, the ROC is regenerative, as it needs to be, on three levels. Soil, yes. It also recognizes the rights of agricultural workers and communities to economic stability and fair wages. It allows farm animals their dignity and a natural life.

Patagonia is not the only community to recognize the need to go beyond organic. Our key partners in this enterprise are the Rodale Institute and Dr. Bronner’s. We have much to learn. Our next steps are to pilot and scale this holistic regenerative standard for both food and fiber, as we’re doing with cotton growers in India. Even now, though, you can enjoy Timeless Seeds’ regenerative organic lentils in Patagonia Provisions® Organic Savory Seeds. They’re just snacks, but we think of them as seeds of hope.