Cochamó Por Siempre

Inside the efforts to protect Chile’s Cochamó Valley from developers and overtourism.

Listen to the story

This story was translated into Spanish by Rafael Olavarría. Para leer la versión en español, haga clic aquí.

Nine pitches up Trinidad, a nearly 3,000-foot granite wall, I focus on finding a good hand jam and place my sore toes squarely below my body on a small ledge. I clip into a well-placed cam, free my other hand and pivot out, leaving my small bubble of intense focus to look out at a soaring condor, silently circling our position on a 10-foot wingspan.

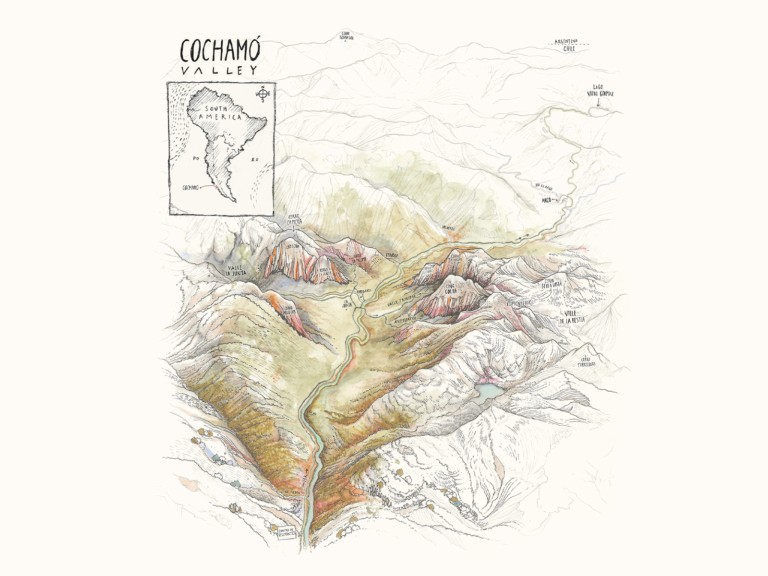

Below, I can see the main river and the area known as La Junta, the epicenter of outdoor recreation in Cochamó Valley. This southern valley spans from Chile’s western Pacific inlets eastward to nearly touch Argentina’s border. Endless carpets of rainforest unfurl below me and lead down to the river that weaves between patches of green meadows. Thanks to two decades of local resistance against logging roads, hydroelectric plants, high-end tourism investment and real-estate development, this place has remained relatively unchanged since the early 1900s.

Miguel Boehm jams on the 3,100-foot, 19-pitch stunner Positive Affect (5.12b) on Arco Iris. Photo: Catalina Claro

Lonely Planet guidebooks first labeled Cochamó “the Yosemite of South America” in the 1990s. The resemblance is hard to miss: big walls, a Merced-like river, green meadows and numerous waterfalls, breathtaking nature. However, Cochamó is more like Yosemite in 1890, before the race to build roads, hotels and shopping centers for tourists. As the comparison has been repeated throughout the last decades in the ongoing struggle to protect this place, those of us who love Cochamó are, in fact, fighting to keep it from becoming the Yosemite of South America.

“To describe the valley as ‘Yosemite-like’ is accurate,” says my friend Rodrigo Condeza, who has lived in the Cochamó area and fought to protect it since 2007. “There it ends. Its differences outshine the similarities: dense rainforest, no traffic noise, a Chilean arriero culture, a muddy five-hour ‘entrance fee’ hike, and an epicenter, La Junta, void of parking lots.” The challenge, as ever, is how to conserve what you also want to share.

I’m climbing in Puchegüín, an area in the southern half of the Cochamó Valley that is privately held. In 2022, it was slated to be sold at auction at Christie’s. This area holds most of the climbing walls and hiking trails in the Cochamó Valley—they weave their way through these mountains in an area that encompasses 328,650 acres. How can these glaciated and granite peaks, their forests and rivers be sold off to the highest bidder? Then again, what if the highest bidder could be us?

Vianney Lhoumeau and JB Bettis review their work after spending the day cleaning cracks on their new route, Regalito de la Mañana, in Anfiteatro. Photo: Nelson Klein

I first saw Trinidad in a photo back in 1999. I was a young climber living in southern Chile, and this little-known granite wall made me want to go somewhere without signs and that wasn’t a national park. Six months later, and after five hours of hiking with a 66-pound pack, I reached La Junta’s meadow where I was awestruck by the surrounding rock faces.

The next day, I hiked the steep two-hour trail from La Junta to Trinidad’s base and met a tall, smiling Brazilian named José ‘Chiquinho’ Hartmann. British climber Crispin Waddy bushwhacked for days through the thick underbrush to establish the first access trails and big-wall routes in 1997. Now, Chiquinho and his team are building extensions to these trails and adding a bathroom, working on the valley’s first fully free routes and drawing elaborate topos.

Over the next week, sharing camp with Chiquinho, I started to catch on. I got more satisfaction out of helping Chiquinho build trails for others than I did merely repeating hard routes myself. Truly being a part of a place wasn’t just seeing, climbing and posting photos on social media. Laboring to make it better for the next generation left an enduring satisfaction.

On the deck of an 80-year-old homestead house, camp managers of Camping La Junta pay a visit to their fellow camp managers and neighbors from Camping Vista Hermosa. Left to right: article co-author Daniel Seeliger, Eric Blake, Paulina Bascopé and Silvina Verdún. Photo: Zenón Seeliger

I was too used to climbers boasting loudly about their first ascents. Today, climbers consider Chiquinho’s mostly unpublished routes the area’s classics. One rainy day, I watched as he drew the details of his route on paper, then folded it carefully and placed his topo into a glass jar to leave behind for the next person to use.

In 2004, my then-pregnant wife, Silvina Verdún, and I bought land and moved into the valley. We’d met five years earlier while climbing in Mendoza, Argentina, and together we opened the area’s first campsite, Camping La Junta, in a 5-acre meadow beside the river.

At first, we were desperate to receive anyone. We charged $2.75 per night, and our first season saw fewer than 30 people. In between our endless projects, I searched for any opportunity to climb. “Are you a climber? Want to climb?” I asked any visitor who arrived.

We worked and learned. We helped shoe packhorses and lead them and their 176-pound loads up an 8-mile trail to our campground in La Junta, the epicenter for climbing and hiking. In time, we learned that the leaves of the native canelo plant can relieve stomach pain and make an antibacterial cleaning product; that a GORE-TEX jacket doesn’t compare to our neighbor’s homegrown, handwoven wool poncho; and that splitting firewood requires short, precise and energy-efficient chops, not the stereotypical muscle-man swings. Our son, Zen, was born in 2005, and we spent all seasons but winter in the valley until he was a teenager.

There are no major roads in the Cochamó Valley, so if you aren’t traveling on foot, then you’re traveling with the local arrieros on horseback. Photo: Drew Smith

And though climbers’ eyes lit up at the thought of another Yosemite, the reality of staying here was quite different from being in a national park. One such climber and I helped Pelluco Sandoval, a local arriero who lived in Cochamó with his family, separate a calf from its mother that wandered the campground. The next day, over café con leche with milk fresh from the teat, the climber said, “Dude, this isn’t Camp 4, it’s Camp Farm!”

Zen grew. He’d climb trees, swim in the river and crawl onto guests’ laps without hesitation and ask them to read him a book. He ran barefoot across the pampa holding Chupete, his red hobbyhorse that he named after a local arriero’s horse. Zen greeted exhausted backpackers with a purple-stained face from maqui fruit—“Hola, hello,” he’d shout, not knowing what language they might speak.

Four years after starting our project, we met Rodrigo Condeza, a 30-something Chilean neighbor with a neatly trimmed beard, precise conversation and a short, high-pitched ha ha ha that made me laugh, even if I didn’t understand why.

We were all relatively new in the valley, isolated in a paradise far from the world’s gloomy issues, or so we thought. In 2008, a mega-hydroelectric project—seven dams, huge pipes, powerhouses and transmission lines—threatened the valley and thrust us into a fight to stop it. Together with Rodrigo, our spouses and the local Sandoval family, we entered a new phase of our lives. We became land defenders, and this first battle was the start of a major conservation movement that continues today.

Running along the border between Chile and Argentina, surrounded by protected lands and sharing borders with two national parks, the purchase of Puchegüín would make a nearly 4-million-acre contiguous corridor for wildlife habitats. Illustration: Jeremy Collins

“We didn’t really know how to do any of this,” Rodrigo remembers, “but we knew we had to try.” And the more we learned, the more we realized the importance of protecting the place that had given us so much.

Over the months ahead, we introduced as many people as possible to the still little-known Valle Cochamó. The battle took place across 50 separate meetings with politicians, political organizations, tourism directors, neighborhood associations and community groups. We ended each presentation on a slide showing a waterless Cochamó with a fork in the trail and a sign that read, “Which path do we take? Tourism or hydroelectricity? Yosemite or Hetch Hetchy?” Preparing for the worst, Rodrigo and I partnered up to buy six mining claims at $1,200 each in a last-ditch effort to block potential damming sites.

Luckily, the campaign to convince the nation succeeded. In 2009, the Chilean president decreed the river basin as the first water reserve in Chile, protecting the river from hydroelectric plants and halting the current projects. This sparked a local movement dedicated to safeguarding against similar threats. And Rodrigo and I joked that we could let our future riches in potential copper mines expire.

“When I knew the decree was real,” says Rodrigo, “I cried.”

Robbie Phillips and Ian Cooper over 900 feet off the deck on Drew’s Porch (discovered and tidied up by the photographer) on La Junta. Photo: Drew Smith

Yet we soon learned that our new roles as land defenders would never end. Internally, a tourism boom in 2016 brought garbage, unburied feces, illegal fires and camps, drug use and a surge of serious accidents. Tatiana Sandoval, Pelluco’s daughter, led the newly formed Organización Valle Cochamó (OVC) to open a visitor’s center in a rusted shipping container to manage and educate visitors. Externally, we continued to fight against development. Only recently, the movement succeeded in a major campaign against an investor’s proposed 79-lot subdivision and also managed to have a 27,182-acre area declared a nature sanctuary along the northern half of the valley.

Maybe we shouldn’t have been surprised when the valley’s newest threat was actually an old one. Roberto Hagemann, a wealthy investor, had been secretly acquiring numerous land and water rights in the area since 2007, and made no secret about his position on development. Over a span of 15 years, Hagemann proposed the Mediterráneo hydroelectric project and numerous hypertourism projects; Rodrigo, Tatiana, the local organizations Puelo Patagonia and OVC, and the community fought against him every step of the way.

In June 2022, Hagemann acquired the Puchegüín estate and 124 acres right next to our campground. He proposed, yet again, roads, hotels and gondolas for high-paying clientele. But maybe our years of persistent opposition paid off, because he ended up listing Puchegüín for $150 million with Christie’s, right next to other pieces of luxury international real estate and beachfront mansions.

The base of Trinidad, a nearly 3,000-foot granite wall, just before the afternoon sun burns off the clouds. Photo: Zenón Seeliger

That’s when José Claro, the president of Puelo Patagonia, had an idea. Did Hagemann need to be Cochamó’s nemesis? José and Rodrigo ultimately won a supreme court battle against Hagemann in a brutal faceoff over his hydroelectric project in 2017, and his various high-impact development efforts failed to gain local approval. Maybe the attempted quick resale of Puchegüín indicated that Hagemann was on the ropes. José contacted him and began a conversation.

“Reaching an agreement with someone who has been your adversary for so long was clearly a major challenge,” José says. “But deep down in our souls, we both knew we needed each other.”

Eventually, the two sides set their differences apart and negotiated, creating today’s enormous opportunity for the community to buy Puchegüín for $63 million.

It’s a difficult amount to comprehend, let alone raise. The price tag is too high for Cochamó’s local NGOs. Thankfully, over the past two years, large conservation players like Freyja Foundation, Patagonia, Wyss Foundation and The Nature Conservancy joined the fundraising efforts and, together with contributions from individuals who believe in the project, donated nearly half of what was needed. With this alliance, a new coalition called Conserva Puchegüín was born, combining deep local knowledge with international expertise. Right now, Rodrigo continues his fight, albeit a little grayer and with a bit less hair, traveling around the world, meeting with other potential donors and growing a Chilean and worldwide effort.

Silvina and her son, Zenón Seeliger, wade into one of the numerous waterfalls near Capicúa Wall. Photo: Daniel Seeliger

Are we, Silvina and I, hypocrites? Sometimes, over the course of these fights, I’ve admitted to having doubts. After all, we bought land and later campaigned to deny a real-estate developer that same opportunity. We built a campground and refugio but fought investors’ hopes who wanted to develop an Ahwahnee-like hotel or a Curry-Village-like shopping center. Are we so different from them?

But then Silvina reminds me: We raised Zen in the valley. We’ve provided an affordable space for campers and the how-tos for using our composting toilets. The Sandovales take people by horseback through the valley. Rodrigo guides tourists up Trinidad’s trails. Local climber José Dattoli leads mountaineering classes in the Anfiteatro. Cristián “Mono” Gallardo leads volunteers in constructing bathrooms for climbers and hikers in the valley’s higher terrain. Tourism students greet backpackers at the visitors’ center. The local arrieros help build bridges and planks over difficult sections of the trail. Twenty-five years after he first started establishing climbing routes, Chiquinho still returns nearly annually to help with trail work, improve upon his own routes and pack out garbage. We have invited people in, but at a scale that the valley and the community can accommodate.

If you allow it, Cochamó makes a deep connection within you. We get our hands dirty and our boots muddy and sweat into the land. A seed is planted. These threats we’ve faced have come mainly from an outside vision that pushes its way in. Our community’s vision sprouts from within and pushes its way out.

“If I have kids,” Zen, now 19, says, “I’d like to raise them there among the huge trees and little animals … in Cochamó’s nature. There’s something powerful and beyond ourselves.”

Climbers need only navigate a small handful of steep snow patches in Cochamó, like when nearing the peak of El Monstruo. Michael Versteeg leads one of these on pitch 28 of La Presencia de mi Padre. Photo: Larz Krause

Robbie Phillips shortly after unlocking the 5.14d crux pitch of his and Ian Cooper’s unfinished 2,300-foot project on La Junta. Photo: Drew Smith

Miguel Boehm on the immaculate big-wall route Entre Cristales Y Cóndores (5.13b). Photo: Catalina Claro

Help Protect Cochamó

Please join us in the effort to conserve Puchegüín and Cochamó. In a few short minutes, you can play a small role in creating one of the largest wildlife corridors in Latin America and a thriving future for the region’s communities, critters and ecosystems. Visit Conserva Puchegüín for more about what you can do and to donate.