Blood Memory

What if we could pass our love of a certain place through generations?

All photos courtesy of Jake Young

Black oaks gave way to Jeffrey and sugar pine as I slowly climbed out of the Central Valley into the Sierra Nevada. Steeped in the pressure cooker of the Bay Area, I was thirsty for clean mountain air, varnished rock and the scent of warm pine. If I heard another software phrase like B2B SaaS Platform one more time, I swore I was going to eject from society.

Situated between the more popular Tahoe and Yosemite areas, Highway 108 is my secret passage to the Sierra. My destination: Lundy Canyon, a steep, aspen-filled valley near Mono Lake. Out of all the magnetism of the eastern Sierra, something about this canyon kept drawing me back. It was already late autumn, and I wanted to fit in as many trips as I could before the pass closed for the winter.

Signs for Twain Harte, Mi-Wuk Village and Pinecrest lit up as my headlights tracked the road. The drive up the western side is gentle. The Sierra lies on a fault block, tilted over millennia, creating the green, rolling foothills made famous by the Gold Rush. The east side is different. In a matter of miles, the road plummets thousands of feet directly to the valley floor. As I drove over Sonora Pass, the Sierra crest blocked the anxieties of the western side. I crawled into the back of my truck near Buckeye Hot Springs to sleep.

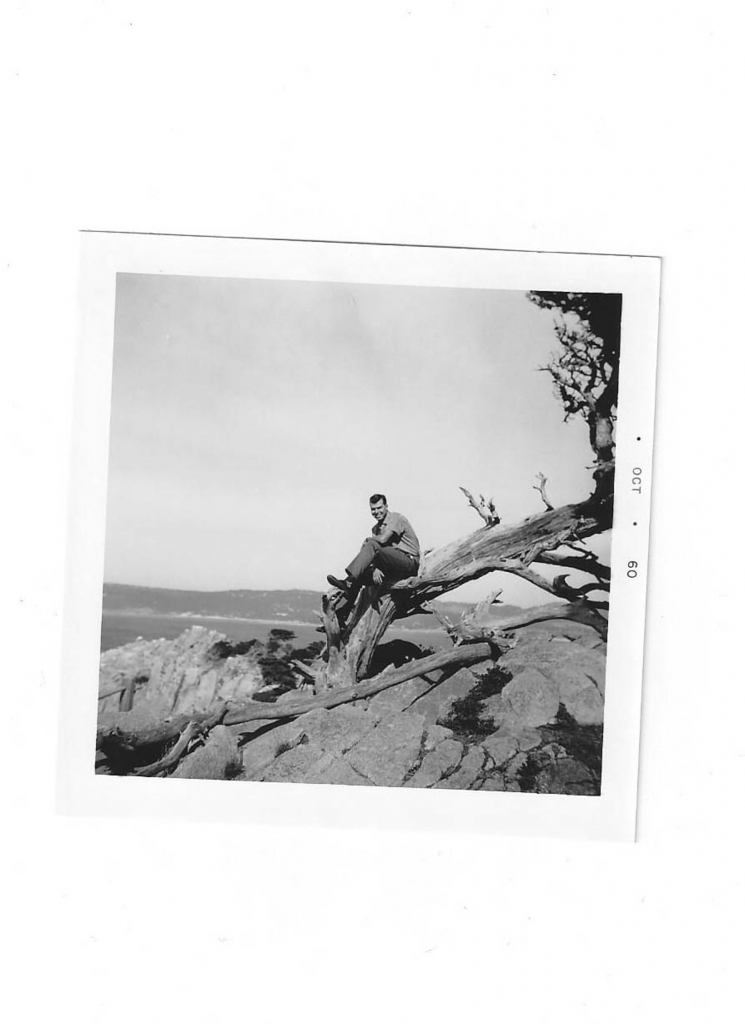

The author’s grandfather poses for a photograph somewhere in the Sierra.

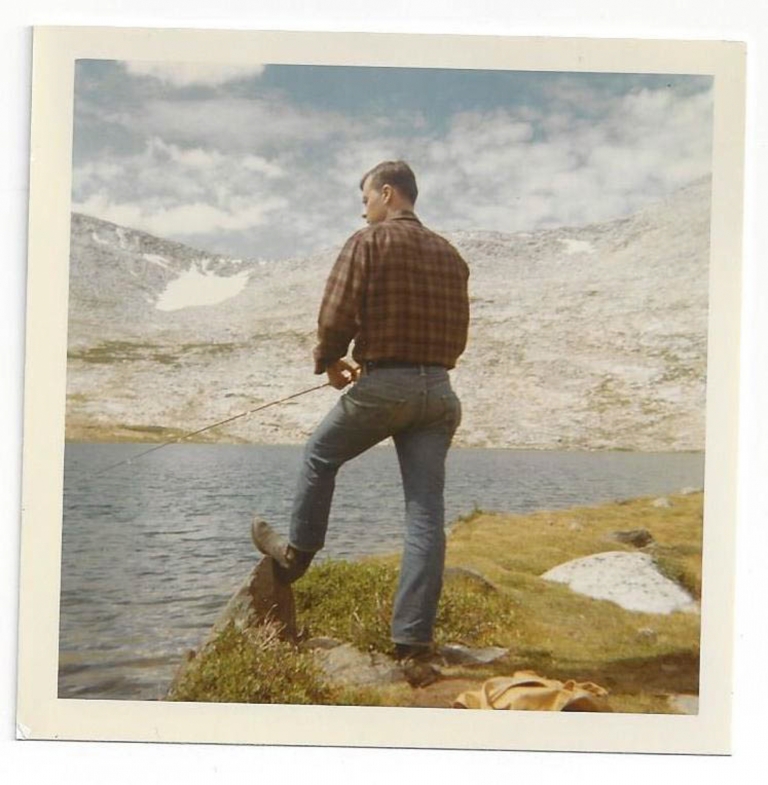

In the early 1960s, my grandfather uprooted his young family from Orange County, California, to Bishop, a small town located in Owens Valley on the eastern side of the Sierra. He wanted to raise his family in the mountains. He landed a job as a delivery manager for Farmer Brothers Coffee and lived with his wife and four kids in a 700-square-foot, 1900s-era home attached to the warehouse where the coffee was stored. It was so run-down that my grandma jokes she had to pull grass out between the floorboards in her bedroom. Granite monoliths were my grandpa’s view as he distributed coffee to the communities dotting the sage-filled plain. He would greet each customer with mirrored aviators and a mustached smile. Sometimes the orders would come in late if the fishing was good.

When I was 4, my grandpa lost a battle with colon cancer. Too young to remember much, I have only one distinct memory of him. He used to stuff toilet paper in his trucker hat so it would hold its shape. I still don’t know if he was serious or just trying to make his grandson laugh. Yet, although that’s the only memory I have of him, stories from my family filled in many of the details. My grandpa was a cave diver, a paraglider, a mountain climber and a fisherman. He was a father, husband and grandfather whose contagious spirit still lives on in our family today.

I grew up far from the rain shadow of the eastern Sierra, in a small town in South Dakota’s Black Hills named Spearfish. After my grandpa’s death, my grandma lived with us for a while. My older brother and I were what you might call “free-range children.” There was no shortage of misadventure as we explored the ghost towns, abandoned gold mines and trails of the Black Hills National Forest. My grandma always liked it when we came home dirty, bruised and battered.

Lundy Lake shows off its colors in early October.

Those who knew my grandpa, and subsequently met me, have always noticed and pointed out sometimes-uncanny similarities. For example, we both share a mischievous cowlick in our left eyebrow. The fact that we look similar is not a surprise. But it is harder to explain how mannerisms, behavior and reactions to our environment are passed through our bloodline. From facial expressions and body language to our shared quest for peace on the east side, something else was passed down through my genes besides a cockeyed brow. Could it be possible that we have some type of ancestral or blood memory? That we share a pathway along which stories are passed down not orally, but through our bloodline?

Turns out, there might be something to this. A relatively new field of science called behavioral epigenetics aims to answer that very question. There is some evidence implying that not only did you inherit your flat feet from your great grandpa but also his resilience to stress or predisposition to depression. That is, it’s possible that behavioral expression from environmental factors, whether good or bad, can be passed down through generations.

When I woke up at the hot springs, I knew something was wrong. I’d parked my truck on level ground, but the blood rushing to my head told me otherwise. After surveying the area, I realized one of my tires had gone completely flat. I found some friendly van-lifers with a portable compressor and located the leak. It was small enough for me to make it to town a few miles away. My first stop was the Bridgeport Shell station where I filled my mug with burnt black coffee and asked the old attendant if they had any patch kits. He rejected my money and apologized because they didn’t carry any. As I walked out, the other attendant brought a large Farmer Brothers Coffee–box out of the back to restock. I imagined my papa trading fishing stories and jokes with guys like these as he dropped off the station’s delivery of coffee. I put on my spare and headed south toward Lundy Canyon, with my grandpa’s coffee in hand.

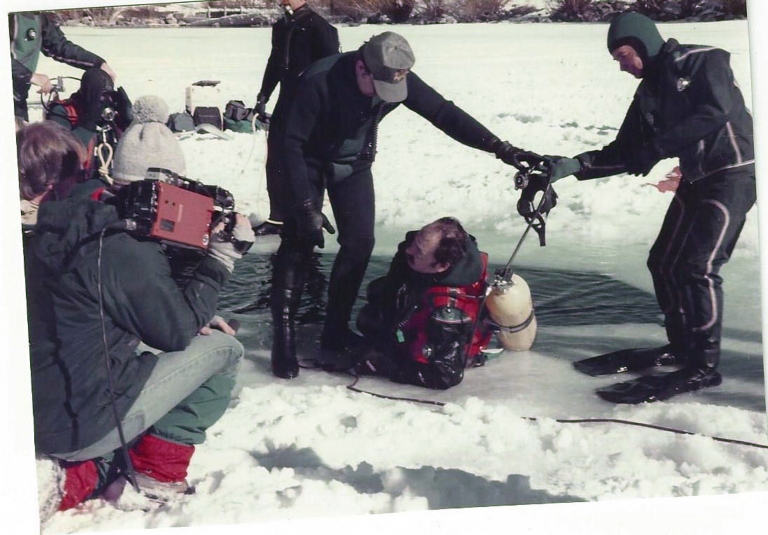

Bruce Humphreys emerges from an icy Convict Lake after a training dive with the Inyo County Sheriff’s Department.

The Sierra has always held a mythological significance in my household. None of us would be here without it. My half-ski-bum parents met after my mom ran out of gas outside of South Lake Tahoe, where my dad picked her up on the side of the road. Every time we visited Tahoe, my siblings and I groaned as we were forcibly taken down memory lane. Although we were in South Dakota, Ansel Adams took up permanent residence on our walls, and my mom would always point out Mount Tom in truck commercials. Dreams of the Sierra were planted early. After high school, I moved out to California. I was finally going to be able to add my own thread to the Sierra stories that tied my family together.

During my college summers, I narrowly escaped tech and finance internships by working as a hiking guide at a summer camp near Lake Tahoe. On a day off, I drove down Highway 395 to start exploring the area that I had heard so much about. I started hiking from Twin Lakes and navigated the seemingly endless RV resort at the mouth of Robinson Creek. After cooling off in one of the alpine lakes, I buried my feet in the warm sand, the sun pinching the water from my back. The sublimely still, inverted image of Crown Point stretched out from the shore of Barney Lake in Hoover Wilderness. I remember getting back from that trip and sitting in the camp workshop talking to the head of operations and maintenance. I had convinced myself that he had seen every corner of the Sierra in his decades-long exploration of the range. I told him I needed to get back to the east side. “Yeah,” he said, “it just gets into you, doesn’t it?” He drew a crude map of his favorite spots with a carpenter’s pencil.

To what extent our behavior is defined by our relatives’ memories and experiences is disputed. For years, DNA has been widely accepted as the only way to transmit biological information to offspring. The field of epigenetics is starting to disrupt this idea, as animal studies have shown that gene functions can have heritable changes without changing the DNA sequence. In one study, mice whose parents had received shocks alongside the smell of cherry blossoms exhibited a fearful response to that smell. Anecdotal at first, research is now producing clinical results suggesting that humans are affected by parental stress and trauma. A study of the transgenerational effects between Holocaust survivors and their children showed that the children had an increased likelihood of stress disorders due to changes in their genes’ expressions. On the flip side, there is also evidence showing that a healthy maternal care environment for infants can cause epigenetic modification resulting in positive mental health outcomes. Although it’s not transgenerational, there is a possible pathway for the transmission of environmental experiences on the epigenome. Besides stress reactions, however, scientists have yet to come to any concrete conclusions about whether behavior or responses to an environment can be passed down epigenetically.

My grandpa always had a vigor for life. No matter how ordinary, every day was made into an adventure. After work, he would frequently take his four children fishing in the Owens River. Sometimes he would even wake up my grandma early to play a game of darts before leaving for work. During every free minute of his life, he devised a plan to have even more fun. Even as his life was coming to an end, he would still go paragliding or scuba diving under the ice of Convict Lake in the foothills above Bishop. Whether its sneaking in a quick surf between work meetings or finding 100 yards of mountain bike singletrack in Golden Gate Park, I try to fill my days in similar ways.

Bruce Humphreys enjoying one of his favorite activities, fishing in the Sierra.

A perpetual golden hour painted the rough dirt road past Lundy Lake. Red crowns topped the golden aspens like matchsticks ready to ignite in a riot of color. Bright willow thickets lined the soggy meadows, taking one last look at their reflection before winter. Just as I was about to head up the trail, an older woman hollered out from the side of her car. Considerate of the other leaf peepers, she wanted some help parking so her spot didn’t block the road. She parked her car and started putting on her boots while sitting on a log. I sat down, and we exchanged a few sentences about the fall foliage. “My best friend died last month,” she said without much warning. “Breast cancer.” Even though they lived in Los Angeles, she told me that they used to come here every fall to hike, just the two of them.

I sat a few miles into the canyon near one of the cascades on Mill Creek contemplating the precious stillness of this wild place. I shared the space with a few birds but was otherwise happy to be alone. There was a familiarity and comfort here that was inextricable from the canyon. According to the Mono County Tourism website, “Lundy Lake is one of the most overlooked and easily forgotten drive-to lakes in the eastern Sierra.” Its proximity to the entrance of Yosemite, Bridgeport and other east-side treasures makes it easy to miss. In the fall, the valley is adorned with the yellow hues of aspen groves and willow thickets. The winter brings frozen ice flows and brittle sage brush. Scores of waterfalls roar through the spring and summer. Each season the canyon transforms, the change amplifies its magnetism.

When I got home, I posted some pictures on social media. None of my family lived in the eastern Sierra anymore, and they always appreciated photos from this place they loved. A few days later, a small red notification appeared on my phone. It was a comment from my grandma. I was expecting something along the lines of “Beautiful!” or a combination of nature emojis. Instead, there was something else. “Lundy Canyon!” it read. “That was Papa’s favorite spot.”

A mingling of last year’s snow and some early-season flurries cap the southern edge of Lundy Canyon.

My grandfather’s memories were written into that same canyon I’d fallen instantly in love with—every cast of his line and every trout released. The hard moments were there, too, as the soothing and restorative mystery of the eastern Sierra quietly eased his fears over leaving his family too soon. And there is still more of his story to discover within the palisades of the eastern Sierra and within myself. All of these times that I had visited Lundy, I was simply bringing the part of him that was in me to our favorite place. We seek these wild places our loved ones roamed to feel a connection to them—to better understand them and through that process, understand ourselves. I visit Lundy Canyon to visit my papa. I hike the trails where his boots struck the gnarled aspen roots. I drink from the streams where he knelt with trout in his hand. His laughter can be heard in the roaring falls and quaking aspen leaves.

I asked my grandma what was so special about Lundy. “It was so quiet,” she said. “I think it filled his soul.” His love for this place gave me memories of a place I had not previously been to but was meant to find. Maybe we all have a subtle connection to our family’s relationships with the land that’s waiting to be expressed in some form or another. We just have to go find it.