Beyond and Back: Scott Parrish

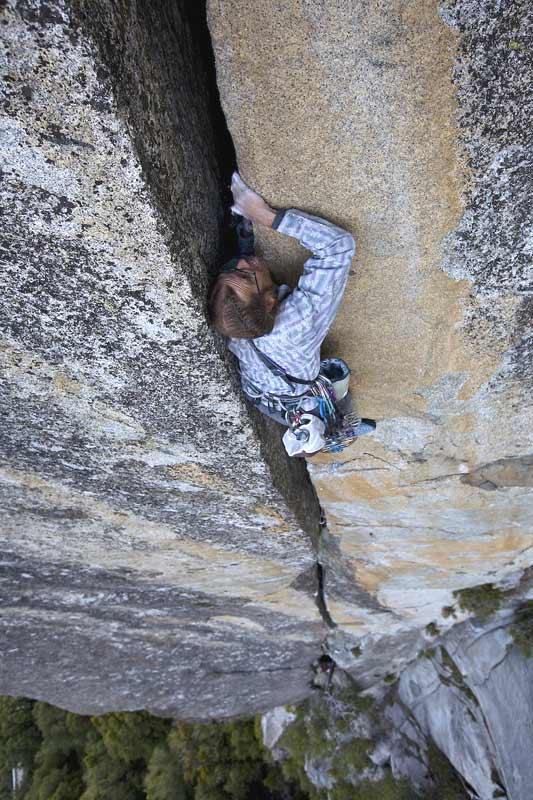

Scott Parry climbing “Steppin Out” 5.10d, Yosemite Valley. Photo: Jeff Johnson

Scott Parry climbing “Steppin Out” 5.10d, Yosemite Valley. Photo: Jeff Johnson

Phew … I’m back! Finally. Got back a couple months ago after being out of the country for half a year. Long story, too long. I’ll get to that later.

You know how it is when you come back from traveling; an estrangement occurs. Re-entry is tough. You gotta take it slow. So I disappeared into Yosemite Valley for the spring.

One morning while wandering through Camp 4 looking for a climbing partner, I came across Scott Parry. A friend had introduced us before but it had been brief. I’m always a little wary of climbing with strangers. You never really know what you’re getting into till it’s too late. And half of climbing is spending a lot of in-between time together: long approaches, re-racking on ledges between pitches, beers at the end of the day, etc. You better enjoy this person’s company or the experience might leave you bouldering most of the time, by yourself.

At first impression Scott was intimidating to me: reddish hair pulled back into cornrows, braided pigtails, reading glasses and an intense, all-encompassing look in his eyes. His generic, industrialized work-wear was all but ripped to shreds, at the shoulders and at the knees. Gnarly. But maybe it was his nickname that rattled me: Savage as some call him, a result from his penchant for climbing off-widths, where he says, “You gotta dig deep to climb off-widths – get in there and go savage.”

As it turns out we both had similar tick lists and I got the vibe that he is also weary of climbing with strangers. I said I could use some off-width training so we agreed to do some laps together on the Generator Crack that afternoon.

Scott tied in first and I saw him slither up the 5.10c off-width/squeeze chimney like a lizard. It took him less than a minute. I got in the thing and had the typical wide crack experience: grunting, sweating, and gasping for air. After exhausting ourselves on consecutive laps, Scott described to me his passion for off-widths.

“Off-widths,” he said with an excited tremor in his voice, “are some of the proudest, most aesthetic lines in the world – they’re usually the most splitter, the most sustained lines in any given area. And for the most part they are usually empty – very few people enjoy them.”

Scott’s favorites are the notorious Chuck Pratt routes: Entrance Exam, Twilight Zone, and Crack of Doom, to name a few. “That guy,” Scott continued, “was a master technician … with huge balls and an eye for perfect lines.”

I was to find that below Scott’s rough exterior was a kind, soft-spoken man – respectful and full of integrity. Everything for him seemed to have purpose: the way he moved, the way he talked, the way he listened. And there was intensity in his eyes when he looked at you, like he was holding onto every word, breathing in the entire experience no matter how trivial. I was to find there was something driving this in-the-moment awareness that surrounded him.

Scott had lost the love of his life a few months earlier. She was his best friend, climbing partner, lover, and life partner. Her name: Susanna Lantz. She was killed in an avalanche while skiing the Chickadee Valley in Kootenay Park, British Columbia. This tragedy would slowly reveal itself as Scott and I began knocking off our tick list around the Valley.

“It changed everything for me,” Scott said while racking up one morning. “I look at life way differently now.”

Scott is an arborist. He basically climbs trees for a living. He lives and works in Placerville – a small town just below Lake Tahoe in the western foothills of the Sierras. It’s a simple existence on the edge of an increasingly complicated world.

“I came to a point in my career where I could be making a good amount of money if I took on more work and more responsibility. But I recently told my boss that I wanted to work less, maybe three days a week, four max. I just want to climb and hang out with my friends – enjoy life, you know? That’s what’s important. Our time here is so short. It’s all about now.”

Scott’s mode of transport is a Honda XR 650, duel sport motorcycle. For road trips he has designed a custom plywood platform for his saddlebags – just enough to carry his climbing gear, some clothes and a bit of food.

“I don’t need much,” he said. “I live in a simple trailer and eat simple, healthy food. I don’t drink, don’t smoke or do drugs. It’s amazing how little you need.”

Walking up the talus slope one afternoon, on the approach to Arch Rock, Scott stopped and pulled something from his shirt pocket. “Here,” he said handing it over to me. It was a laminated photograph of Susie belaying at Indian Creek. “I bring this with me wherever I go.” He took one last look at the photo before carefully placing it back into his pocket then smiled and gazed up at the Valley walls. “She’s always with me no matter what I’m doing.”

The nights in-between our climbs I would lay awake in my van thinking about Scott and what he was going through. I could only empathize with him for I never had something so tragic happen to me. But his story had affected me on so many levels; it had struck such a strong cord. Returning home from being gone so long I had developed an acute sensitivity to all things. Suddenly, every detail of life, no matter how tiny, held great importance. Such are the effects of travel, I guess. This is all good in theory but it was hindering my ability to assimilate – I was having a difficult time getting back into the swing of things. One must be calloused to succeed amongst the rat race. I feared this callousness.

Re-racking on a tiny ledge, half way up the northeast buttress of Higher Cathedral, Scott said to me, “I’m not gonna sugar-coat this thing and say Susie’s death has given me some sort of revelation or epiphany, like when people say, ‘there’s a reason for everything.’ That’s bullshit. There’s nothing good about her dying. I’m pissed off about it. I’m angry, you know.”

It got quiet. All I could hear was our gear clinking as we passed it back and fourth. Then a swallow darted by our heads startling me like a dive-bomber. A light wind swept up the face and gave me a slight chill. It was Scott’s lead. He was looking out over the Valley, thinking. “I’m just climbing,” he said. “I just wanna climb.”

The next morning Scott and I were in the Lodge parking lot, organizing our gear outside my van. Out of the blue, this older African American gentleman appeared. He walked slowly towards us with his back slightly bent and his hands supporting his hips, stiff, like the short walk was a painful. He got to us and stood erect. He looked at all our gear spread out on the ground. Smiling, he said, “Looks like you guys have it all figured out … traveling around, sleeping under the stars … climbing …”

With his red, sparkling eyes, he looked us up and down as if to find evidence to his assumptions, and said, “You’ve distanced yourself from all the crap society has to offer, making your own world, creating your own experiences. I like that. I drive a tour van for a living. Only a few more years till I retire. And I aim to do the same.”

He cupped a hand over his eyes and looked up at the towering, granite walls, then turned his attention to Yosemite Falls – the mass of whitewater was billowing in the wind. The man seemed to be gathering his thoughts. He continued: “If people did more of this then I think they’d spend less money on psychologists and pills. Man was meant to be out there around nature.”

I glanced over at Scott. He was smiling, nodding his head. I think he understood this more than the man would ever know.

All photos by Jeff Johnson

All photos by Jeff Johnson