Colin Haley Recaps His 2010 Alaska Trip

Bjørn-Eivind Årtun and I have just come out from a 37-day trip to Denali and Mt.

Foraker, which was partially funded by a Mugs Stump Award and the Norwegian Alpine Club (NTK). Here is a report of what we did. [Bjørn-Eivind high in the Messner Couloir on our first visit of the expedition to Denali’s summit. Photo by Colin Haley]

Editor’s note: Patagonia ambassador Colin Haley takes the mic today for a recap of his recent trip to Alaska. Colin and Bjørn-Eivind Årtun won a Mugs Stump Award grant for the climb they would attempt on this trip: A single-push first ascent on the southeast side of Alaska’s second-highest peak, Mt. Foraker, one of the biggest unclimbed faces in the central Alaska Range. How did it go? Pull up a chair, grab your beverage of choice and enjoy a great read from one of America’s premiere alpinists.

We flew onto the Kahiltna Glacier on May 13, and immediately started up Denali’s West Buttress route to acclimatize. We soon established a basecamp at the 14,200 ft. camp on the West Buttress to stay for a while. On May 21 we attempted to climb and ski the Orient Express route, but turned around and skied from 17,500 ft. in the face of dangerous wind slabs. On May 25 we climbed to the summit of Denali via the Messner Couloir and returned to the 14,200 ft. camp in 9:15 roundtrip. On May 29 we climbed to the summit of Denali again via the West Buttress route in 8:10 roundtrip.

[Our first acclimatization venture to the 17,000ft. camp was via the Rescue Gully. Colin perched on some rocks next to the 17,000ft. camp with Foraker behind. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Hanging out at the 14,200ft. camp in the igloo of the “Leningrad Cowboys.” From left to right is Stephen, Justus, Bjørn-Eivind, Colin and Sean. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Bjørn-Eivind kicking steps up the Orient Express. We went to approximately 17,500ft. but then encountered scary windslab and skied back to camp from there. Photo by Colin]

[We passed much of our acclimatization time skiing laps in the basin above the 14,200ft. camp. Colin catching a bit of air. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Colin on the summit of Denali after our climb of the Messner Couloir. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Our next trip to the summit was a few days later, via the standard West Buttress. Bjørn-Eivind on the summit for our second time. Photo by Colin]

On the evening of June 6

we departed the 14,200 camp with light packs to attempt the Cassin

Ridge, with hopes of breaking the speed record established by Mugs

Stump in 1991 (he climbed the Cassin Ridge in 15 hours, and 27.5 hours

roundtrip from the 14,200 ft. camp). The forecast was marginal, and our

attempt was preceded by a lot of new snowfall, but we had already

waited too long for a good weather window. Rather than descend all of

the lower West Rib route, we opted to approach via a variation to the

West Rib, the “Seattle ‘72 Ramp,” established in 1972 by Alex Bertulis,

Jim Wickwire, Robert Shaller, Tom Stewart, Charlie Raymond and

Leif-Norman Patterson. This approach worked excellently, and we were

soon melting water in the bergschrund at the base of the Japanese

Couloir.

We crossed the bergshrund at 22:40 and began climbing up

the Japanese Couloir. Above Cassin Ledge we made a route-finding error

and accidently climbed a mixed chimney that was more difficult than

necessary. While climbing the first rock band the weather took a turn

for the worse, and the mostly cloudy skies turned completely cloudy and

started snowing. We had decent snow conditions until the top of the

third rock band, at 17,000 ft. (although much more hard ice on the

icefields than most years), but then began to wallow considerably in

deep, fresh snow. We had made excellent time up to 17,000 ft. (about 11

hours) and were confident that we would break the speed record, but

that hope began to disintegrate as we worked through snow sometimes

waist-deep on the left (west) side of the ridge. The snow worsened

closer to the summit ridge, and the final 1,000 ft. to the summit took

us over three hours. We finally reached the summit at 15:43 for a time

of 17 hours from the base. We took our time down the West Buttress

route, and when we arrived back at the 14,200 ft. camp 28 hours had

elapsed. We brought a 20 meter rope for the approach, but simul-soloed

all of the route.

[Colin just past the most difficult section of the Japanese Couloir. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Bjørn-Eivind arriving at the ridgecrest at the top of the Japanese Couloir. Photo by Colin]

[Bjørn-Eivind climbing through the Cassin’s crux rock band, just above the Japanese Couloir. We realized after the climb that we accidently climbed this more-difficult chimney unnecessarily, and the correct gully was further to the right. Photo by Colin]

[Colin in the second rock band. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Colin getting frosty on the upper Cassin. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[The last 1,000ft. to the summit ridge took us over three hours, due to deep snow and our fatigue, but Bjørn-Eivind did a great job with the majority of the trail-breaking on this section. Colin following. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Colin on the summit of Denali for our third time of the trip, a bit more tired this time! Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

After our climb of the Cassin we packed up

our camp at 14,200 ft. on the West Buttress and descended down to

Kahiltna basecamp. Ever since our first week on the glacier we had not

experienced consecutive days with good weather, and still the forecast

was not optimistic, so it seemed unlikely that we would attempt the

main objective of our expedition: a new route on the Southeast Face of

Mt. Foraker. After a few days in basecamp the weather forecast called

for one day of high pressure, and we thought we might as well pack our

backpacks and ski over to the base of the face to check it out. We

skied to the base of the face in a whiteout, and never even once that

day were able to see the wall that we hoped to climb. We set up our

tent in dumping snow, and assumed that in the morning we would simply

ski back to basecamp. However, we awoke at 4:00 am the next morning

(June 13) to clear skis, and made a hurried decision to launch.

We

skied from our campsite up the glacier to the base of the face, and

then cached our skis below a protected rock buttress at 6,800 ft. The

lower portion of the face (before we branched off of the previous

route, False Dawn) is

serac-threatened, and so as soon as we left our skis, at 6:00 am, we

set off simul-soloing as fast as we possibly could. We raced up a

narrow snow couloir to the left of the main serac (but still threatened

by a serac on the French Ridge) with steps up to AI3, and then made a

right-ward traverse to above the main serac and out of danger. We spent

a total of two hours and ten minutes in what I consider dangerous

terrain, although we never saw anything come down from these seracs.

Above the dangerous terrain we climbed up a hanging glacier, and then departed False Dawn,

climbing up to the base of the large diamond-shaped wall that we hoped

to climb. At the base of the wall we stopped to rest, eat, melt snow

and bust out the ropes. The wall itself is about 3,000 ft. tall, and

comprised of first a large left-trending ramp system, and then a large

right trending ramp system. We climbed a lot of ice runnels, and some

tricky mixed bits. The rock was mostly good granite, but the technical

crux came on a section of crumbly M6R.

[After going to sleep amidst dumping snow we had assumed our last chance to try Foraker was gone, but we awoke surprisingly to clear skies. Colin at our camp below the face the morning that we started climbing. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Bjørn-Eivind on the lower part of False Dawn, almost out of the dangerous terrain. Photo by Colin]

[Bjørn-Eivind past the serac danger and almost to the hanging glacier on False Dawn. Photo by Colin]

[Bjørn-Eivind departing False Dawn, and kicking steps up to the diamond-shaped rock wall. Photo by Colin]

[Colin starting up the first, left-trending ramp. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Bjørn-Eivind’s view up the first of the route’s two crux pitches. This mixed dihedral was quite steep, but with excellent rock and protection. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Bjørn-Eivind arriving at the top of a pitch of rotten ice. Photo by Colin]

[Bjørn-Eivind on the right-trending ramp. Photo by Colin]

[Colin on a very precarious cornice near the top of the right-trending ramp. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Colin on the route’s second crux pitch: not as steep, but with rotten rock and bad protection. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Colin almost to the top of the rock wall. We really wanted to brew up at this point, but couldn’t find anywhere to do so. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

At the top of the rock wall

we had hoped to brew up, but there was still not a single ledge big

enough to chop a butt-seat, so we kept climbing through the night up

interminable 60-degree ice slopes to the junction with the French

Ridge. Climbing through the night, combined with severe dehydration and

wet socks, caused me to develop frostbite on my big toes.

At the

junction with the French Ridge we stopped to rest and melt snow in the

dawn light. Eventually we got on our way again, and slowly began the

long plod traversing under the south summit and on towards the true

summit, quite exhausted. We finally reached the true summit at 13:00,

31 hours after leaving our skis. The skies were clouding up however,

and we scurried off almost immediately, heading down the Northeast

Ridge.

[Bjørn-Eivind on the never-ending 60-degree ice slopes above the rock wall. We really wanted to brew up at this point. Photo by Colin]

[Colin almost to the top of the never-ending 60-degree ice slopes, in the first rays of the sun. Now we really, really wanted to brew up. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Colin looking a wee bit tired upon joining the upper French Ridge. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Bjørn-Eivind was a wee bit tired as well… Photo by Colin]

[Bjørn-Eivind on the upper French Ridge, with Mt. Hunter behind. Photo by Colin]

[The traverse from the south summit to the main summit of Foraker was a long ordeal in our utterly depleted state. Like on the Cassin, Bjørn-Eivind did a great job with the majority of the trail breaking on this last section. Two worn-out climbers on the summit, anxiously watching clouds building all around us. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

We quickly descended 5,000 ft. down the Northeast Ridge, and

then stopped in a convenient crevasse to melt snow out of the wind. We

had planned to continue descending via the Sultana Ridge variation, but

when we exited the crevasse we were greeted with complete whiteout and

50 mile-per-hour winds. After a brief attempt along the ridge we

returned to the protected crevasse. A little while later we tried to

start out again, but again realized we had no chance to continue along

the Sultana Ridge in the blizzard.

Back in the crevasse we

discussed our options. We had half a canister of isobutane left, a

handful of energy bars, no sleeping bags, and no tent or sleeping pads

– staying long was out of the question. We spent the night sitting in

the crevasse shivering hoping for the weather to improve. When in the

morning it was just as bad we decided our only reasonable option was to

descend via the original Northeast Ridge route, established in 1966 by

a Japanese team, as it would be much less exposed to the wind than the

Sultana Ridge. We had no information about it, and I don’t think it has

been ascended or descended in at least a decade, although probably two

or three.

Slowly we fought our way down the 1966 route. Low down

the original route traverses off the rib into an extremely broken

icefall, underneath seracs. We decided it would be safer to stay on the

rib, and began rappelling directly down the unclimbed rock buttress

instead. It was sometimes quite tricky, and included a couple

overhanging rappels, but finally we made it down to the glacier. Once

far enough away from the face that we felt relatively safe from

avalanches, we stopped to melt snow once more, and then began the long

post-holing session back to Kahiltna basecamp. When we finally reached

basecamp we had been awake for about 71 hours, and I was hallucinating

a lot. The toes that I had frostbitten during the ascent had re-warmed

during the descent, and had been excruciatingly painful for most of the

descent and hike back to basecamp.

[Our crevasse shiver-bivy at 12,000ft. on the Northeast Ridge, where we spent a miserable night hoping for the blizzard to abate. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Colin back-tracking while navigating a route through humongous crevasses on the stormy descent down the Japanese ’66 route. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Colin pulling the rappel ropes above the last rappel. Photo by Bjørn-Eivind]

[Bjørn-Eivind on the last rappel, which was almost 50 meters of overhanging rotten rock, into the biggest moat we’ve ever seen (we had to climb a pitch of steep ice to get out of it). Photo by Colin]

[The two of us arriving in Kahiltna Basecamp at 2am, hallucinating quite a lot. The long, post-holing walk across the Kahiltna Glacier was excruciating for my frostbitten toes, so I opted to walk the last section, up Heartbreak Hill, in just my boot liners. Photo by Jacob Schmitz]

My frostbite looks as though it

will heal up just fine (although I might not manage tight rock shoes

for a bit!), but in basecamp I could not yet put on boots, and

Bjørn-Eivind retrieved our camping gear and skis from the base of the

route with the help of our friend, Chris, from Colorado. The whole

climb and descent felt massive, and made the Cassin feel like a small,

non-commiting route by comparison. We named our route Dracula, and the numbers are: 10,400 ft., M6R, AI4+, A0. June 13-15, 2010.

–Colin Haley

[The view of the wall from our campsite, the morning that we started up the route. Dracula is marked in blue. Photo by Colin]

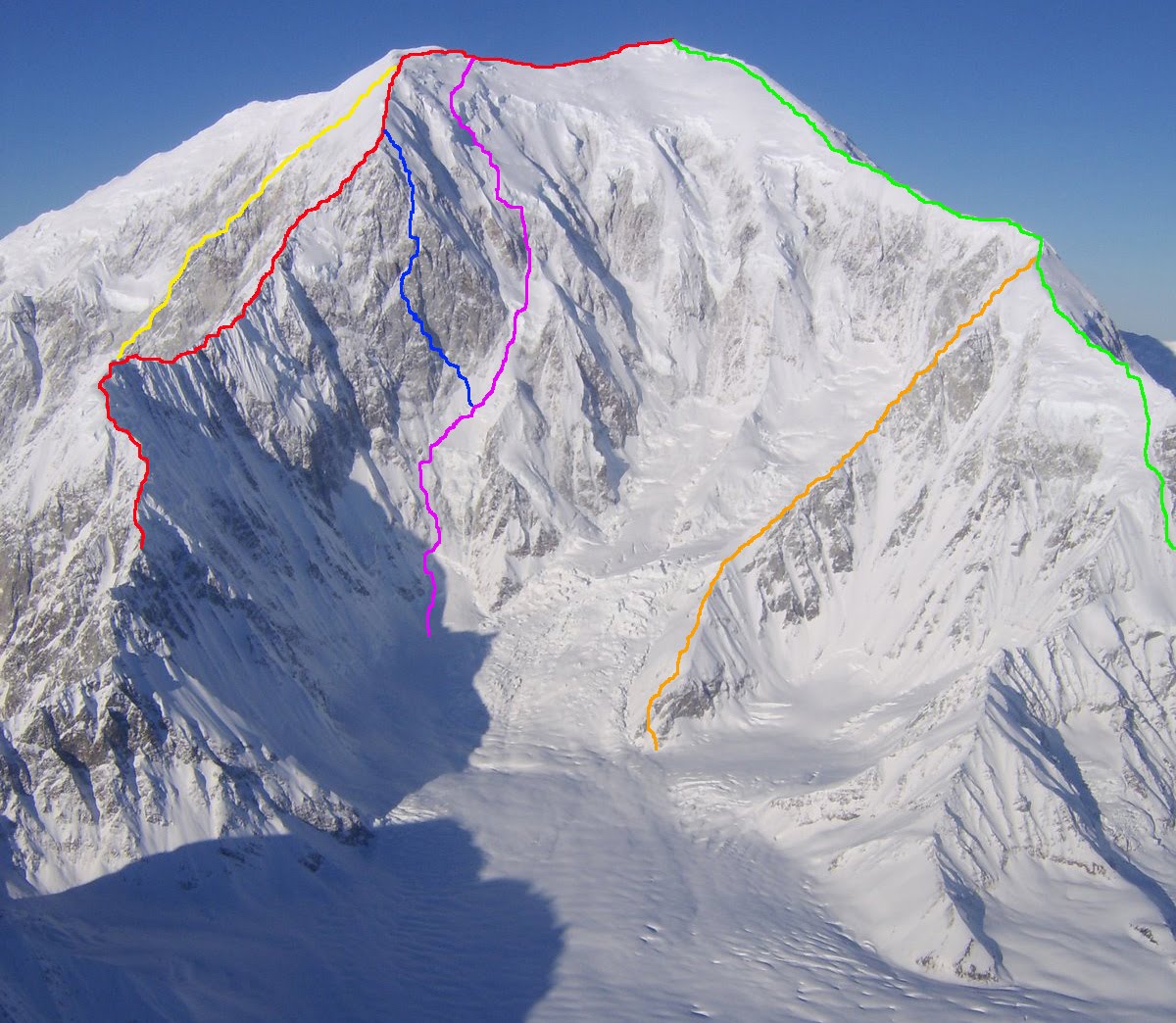

The entire Southeast Face of Foraker, showing all established routes.

GREEN: Southeast Ridge (bottom not shown), 1963, 10,400 ft.

RED: French Ridge, 1976, 10,800 ft.

YELLOW: Infinite Spur (bottom not shown), 1977, 9,000 ft.

PINK: False Dawn, 1990, 10,400 ft.

ORANGE: Viper Ridge, 1991, 6,000 ft. (climbed only to junction with SE Ridge)

BLUE: Dracula, 2010, 10,400 ft.

———————————————————————————————————————

An even more detailed version of this post originally appeared on Colin’s blog Skagit Alpinism. Those interested in beta Colin gathered from this trip on Mt. Hunter and the approach to Cassin Ridge will want to check out the full post.

The last time Colin was in Alaska we received a question about his clothing system. Here’s what Colin was wearing for this trip:

On bottom:

–Capilene 1 Boxer Briefs

–Capilene 4 Bottoms

–Lightweight Guide Pants

–Puff Pants

On top:

–Wool 2 Zip (links to Crew; Zip-Neck avail. this fall)

–R1 Hoody

–M10 Jacket

–DAS Parka

-Capilene 1 Balaclava (look for the R1 Balaclava this fall)

Our thanks go out to Colin for sharing his story and photos. This post is dedicated to Mugs Stump and Joris Van Reeth.