Adrift in the Sage Brush Sea: 8 Days with the Nevada Wilderness Project

Patagonia’s environmental internship program is sending about 20 employees into the field this year to volunteer with nonprofit environmental groups around the world. The company pays employee salaries and benefits for up to a month while they work in D.C., Kenya, Kauai and other locales. Jim Little, an editor in our marketing department, recently spent eight days in the great outdoors with members of the Nevada Wilderness Project (NWP). Here’s his account.

Adrift in the Sagebrush Sea

Loaded to the gunwales with tents and sleeping bags, ice chests stuffed with food and hoppy beverage, in early October we drove north from Reno in a rented Tahoe to spend a week adrift in the Sagebrush Sea. I was tagging along to experience and write about a 4-million acre landscape the Nevada Wilderness Project, Oregon Natural Desert Association and other groups want to connect and protect as a Sage Grouse Conservation Area for the benefit of the threatened game bird and some 30 other sage brush-dependent wildlife.

As you might imagine, rigorous field study entails great sacrifice: hiking soaring escarpments, witnessing herds of swift-hoofed pronghorn, soaking in soothing thermal pools and taking to the air in a private plane arranged by LightHawk for a two-hour over-flight. It also meant hanging out with bright, well-informed (and highly entertaining) people determined to preserve a massive landscape for the benefit of all.

Sage grouse – the bird best known for its thunderous wing flapping, comical mating ritual and sage-infused meat – was once so prolific in these parts that when it took wing flocks darkened the sky. Today, its habitat in decline, sage grouse populations in some areas of the Great Basin are leaning toward extinction. The conservation area would restrict cattle grazing, oil and gas development, poorly conceived renewable energy projects (yes, there are some) and off-road vehicle use that jeopardize sage grouse and the other wild animals. Without a protected conservation area, the bird will most certainly end up on the Endangered Species list, which would put a stop to all activities that threaten it, though by more draconian means.

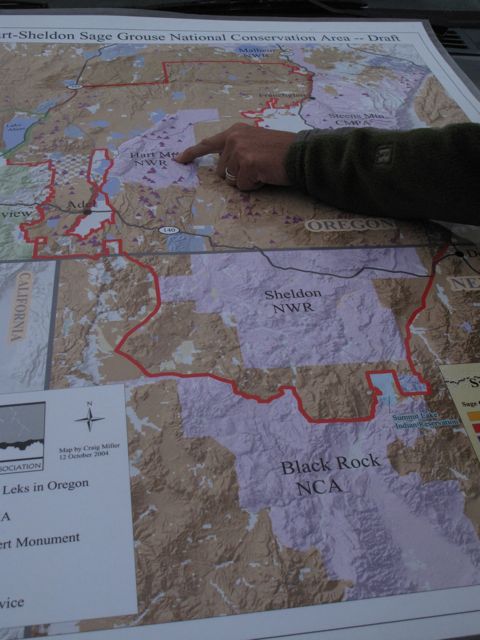

As conceived, the Sage Grouse Conservation Area will one day unite public lands in southern Oregon and northern Nevada. They include the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge in the north, the Sheldon National Antelope Refuge in the south and a swath of public land administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in between, along with some surrounding areas. The BLM land is particularly rich in wildlife, Native American sites and scenery. But like much of the West where grazing is permitted, it’s badly beaten down by cattle.

Uniting these vast landscapes may not be as complicated as say unifying North and South Korea. But in this part of the country, a lot of people view environmentalists and the federal government with the same suspicion as Kim Jong-il, and grazing rights on public lands are thought an inalienable birthright. So it will take some heavy lifting.

Check out my photos to learn more.

[Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge HQ.]

[The refuge was designated in the 1930s to protect pronghorn, the fastest land animal in North America.]

[The Sage Grouse Conservation Area would protect the public land inside the red line on this map for the benefit of sage grouse and some 30 other species that depend on sagebrush.]

[This sage grouse was hit by a prairie falcon, which flew off as our cars approached.]

[It rained about two inches during our week in the Great Basin, an arid zone that averages only about nine inches of precip per year. This ghostly juniper on Hart Mountain was glad it did.]

[Lichen on an ancient juniper.]

[Cows were removed from the Hart Mountain refuge in 1992. Previously hammered by grazing bovines, this creek is staging a nice comeback.]

[In spring, the Warner Valley is covered with water. Shorebirds depend on these ephemeral lakes for food and habitat during their annual migrations.]

[Water falls even in the arid zone.]

[Plush is the nearest town to Hart Mountain’s northern entrance.]

[Paiutes once inhabited this area now managed by the BLM.]

[It was fun to ponder who might have lost this arrowhead and under what circumstances.]

[Nevada Wilderness Project Founder John Wallin (left) and Brent Fenty (Oregon Natural Desert Association, executive director) discuss the challenges of large-scale landscape conservation in this part of the country.]

[A sage grouse view of land recently grazed by livestock.]

[Charting our course to the next hot spring.]

[Hot spring found. Taking the chill off near Crump Lake.]

[Matt Verdieck, a pilot from Bend, Oregon, volunteered his plane and adroit piloting skills to fly us over parts of the proposed Sage Grouse Conservation Area. The flight was arranged by LightHawk, a volunteer pilot-based organization that flies environmental missions in collaboration with hundreds of partner groups.]

[View from aloft of Hart Mountain’s Poker Jim Ridge and the Warner Valley.]

[The Shelon Refuge from on high.]

[Most anything goes on Your Public Lands managed by the BLM.]

[The Bureau of Land Management administers some 18,000 grazing permits, which subsidize ranchers’ use of millions of acres of public lands (many in the Sagebrush Sea) as a feed source for their cattle.]

[Wild horses (and burros) also roam these lands. Though a romantic icon of the Old West, these days they are a source of considerable controversy. Like cattle, they compete with other grass eaters, trample native vegetation and foul sources of freshwater. With no real predators, they multiply quickly. Roundups and relocations are used by land managers to try to rein them in.]

[Mmmmmmmm. Cowboy coffee anyone?]

[Gregg Tanner (checkered shirt) worked for 32 years as a wildlife biologist for the Nevada Department of Wildlife. Now with the Nevada Wilderness Project, he knows the Sheldon Refuge better than most. Tanner generously shared his encyclopedic knowledge with us about the biology and history of the area.]

[Unintended consequences: A homesteading family made their home in 1910 at McKenney Camp, on what is now the Sheldon Refuge. According to Gregg Tanner, they cut down all of the willows in a nearby creek to build these pens. Loss of the willows destabilized the soils, which helped cause the groundwater level to drop. When the McKenneys could no longer access enough water to irrigate their land, they were forced to move.]

[Hand-forged hardware at McKenney Camp.]

[One night at Badger Camp, Gregg Tanner cooked one of the juiciest turkeys I’ve ever enjoyed. He cleared a patch of grass, stuck a piece of rebar in the ground, surrounded it with aluminum foil, impaled a 12-lb. hen on the rebar, placed a stainless steel can over it (don’t use aluminum!), surrounded the can with briquettes and let it cook for 2 hours and 45 minutes. The meat fell off the bones.]

[A hungry pack takes shelter from the rain.]

[NWP’s Wallin and ONDA’s Fenty battle for grazing rights.]

[Though a lot of fence has been removed, remnant barbwire remains on the Sheldon Refuge.]

[Homesteader John Perry built Wall Canyon Ranch in 1910. His wife gave birth to 11 children in this house. Tanner said that shortly after the 11th was born, papa Perry rode off and never returned.]

[Work crews are busy building the 600-mile Ruby Pipeline, which will carry natural gas from fields in Wyoming to southern Oregon. Scraping away natural vegetation like this gives rise to cheatgrass, an invasive that grows all over the Great Basin to the great detriment of native species.]

[Though the pipeline corridor will be replanted with natives, the further spread of cheatgrass is inevitable. An annual that invades open areas with disturbed soils, it can completely alter ecosystems by replacing native vegetation and altering fire regimes. Native to Europe and parts of Asia and Africa, cheatgrass was accidentally introduced into the United States in the mid 1800s and now grows all over the Great Basin.]

[El Paso Corporation paid about $15 million to mitigate some of the harm caused by the construction of its pipeline. Representatives from several environmental nonprofits will use the money to acquire private land holdings in the Hart and Sheldon refuges and to retire ranchers’ grazing rights elsewhere in the proposed Sage Grouse Conservation Area.]

[Pipeline valves the size of pickup trucks.]

[Mountain mahogany lines the ridges.]

[Sweet light just outside the Sheldon Refuge.]

[Local color.]

[Bog Hot: a thermal creek just outside the Sheldon Refuge that was perfect for soaking.]

[Another day, another soak.]