A Better Way to Do Business

In 2012, we published The Responsible Company, the part-Patagonia memoir, part-guidebook for businesses on how to do better by the natural world, written by Yvon Chouinard and Vincent Stanley. Now, as Patagonia celebrates 50 years of business unusual, we are releasing a second edition because, as Vincent explains, we’ve learned a ton. As the climate crisis accelerates, the need for a bottom line that makes environmental and social impact mandatory is more important than ever.

You’ve worn plenty of hats here. What have some of those roles been?

I started out at 20 as an invoice typist, bookkeeper and packer. I wasn’t a surfer, so when the waves were good, I’d be the only one left in the office to answer the phones and take the dealers’ orders. A couple of months in, Yvon tapped me on the shoulder and said, “You’re sales manager now.” I asked, “What’s that?” He shrugged and told me, “You’ll figure it out.” That year we started Patagonia as an offshoot of Chouinard Equipment.

I ran wholesale for about 20 years, in two separate stints. But vocationally, I’m a writer, and when I hit 40, I felt the need to get serious about that, so I stepped down. I led the hiring process for our first environmental manager, wrote product copy for a long stretch, headed the editorial department, ran marketing for a bit. For the past nine years I’ve been director of philosophy. I meet with small groups of employees to talk about company history and values, and how they play out in the workday. It’s a funny word to use, philosophy. I remember asking a friend of mine who’s a real theologian, “I’m thinking of the title ‘director of philosophy,’ but I don’t know if I’m really entitled to use that.” He said, “No, it’s OK.” I’m also a resident fellow at the Yale Center for Business and the Environment, and I guest-teach grad students in design, environmental science and business at other schools. And I support the B Corp movement, speaking with people who want to build their businesses consistently with their values.

And your current hat is co-author of this new second edition. Why write another one?

In the decade since The Responsible Company came out, Patagonia has learned more about how to improve our environmental and social practices. We have a stronger vision of what needs to be done to restore the planet to health, and it’s time to bring that into conversation with our community of customers and allies in other businesses.

We’ve evolved from being a company that supports activists to an activist company. And rather than simply reducing our environmental harm, we’ve discovered, through Patagonia Provisions and regenerative organic agricultural practices, you can give back to nature as much as you take. The new purpose statement and ownership structure reflect that—and are a culmination of 50 years of both accidental discoveries and purposeful work.

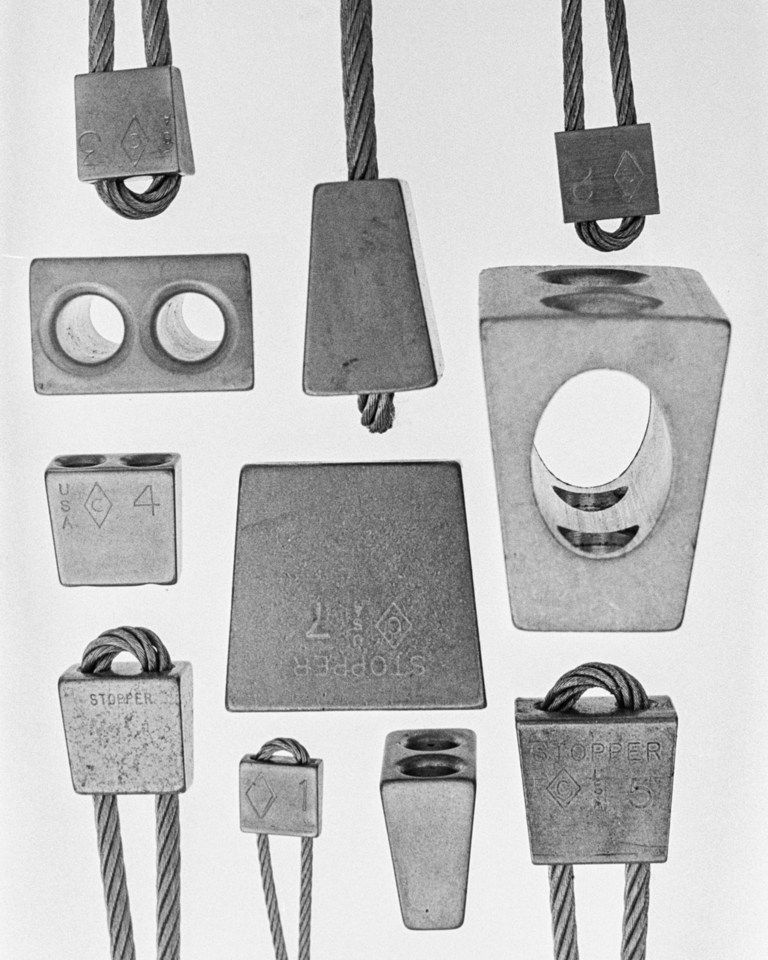

Before clothing, there was climbing gear. Soon after Chouinard Equipment was founded in 1965, pitons became the company’s best-selling product. After realizing that pitons were irreparably disfiguring the rock, Chouinard and business partner Tom Frost pivoted to aluminum chocks that could be wedged in and easily removed without damage. Photo: Gary Regester

The start of a ski jacket at the Forge, Patagonia’s research and development facility in Ventura, California. Photo: Tim Davis

In the book, you talk about “several critical moments in Patagonia’s past that changed our sense of the possible … without knowing we were doing so.” Can you give us some examples?

When Chouinard Equipment introduced chocks as a substitute for the pitons we’d discovered were damaging the rock, they had no idea climbers would embrace the change in such numbers and so quickly.

When we attended a city council meeting where officials urged that the Ventura River be declared dead and encased in concrete, we were moved by the young biology student who argued that instead the river should be brought back to life.

We gave him a phone, a desk and a mailbox. That turned out to be the first step toward giving 1 percent of annual sales to grassroots environmental organizations.

When we discovered how harmful conventional cotton farming was, we switched to organic, not knowing we would have to reinvent and rebuild our supply chain.

Before we came out with the “Don’t Buy This Jacket” ad on a Black Friday, we worried it might kill sales at the busiest time of year. We had no idea that the ad—people called it a “campaign”—would resonate so strongly in its call for more responsible design, manufacturing and consumption.

Patagonia started working with Fair Trade USA in 2012. What growth have you seen in the program both within Patagonia and across other apparel brands since then?

What started with 10 styles being made in Fair Trade Certified™ factories now includes almost all our products. Workers in Fair Trade Certified factories receive a bonus paid by the brand into escrow. An elected committee decides how to distribute the moneys, whether as cash or, for instance, bicycles so employees can get home more easily to their families. Other companies, seeing the success, have followed suit.

In 2007, you helped launch Footprint, our account of Patagonia’s supply chain, including the materials we use and the people who make our products. Sometimes that meant discovering stuff we feared. Was it hard to go public with that?

We worried about alienating suppliers, so if we wrote about a business partner’s problem with wastewater treatment or an overheated factory floor, we would talk with them before posting. The conversations were often difficult but also led to serious mitigations and improvements. One surprise for me was the internal impact within Patagonia. Sharing with all employees what we knew on the design and production side made the whole organization smarter about how our clothes are produced and what the challenges are.

What’s been a challenge of the job that’s made it more interesting?

What intrigues me is how the company has increased its capacity to take on—and meet—progressively bigger challenges. This applies to all our practices, not just design and production. When we outgrew our Reno, Nevada, distribution and service center, for instance, colleagues from operations and finance searched for a second location, driving around from Tennessee to Pennsylvania with realtors who showed them raw farmland and forest as ideal venues to plunk down a 300,000-square-foot warehouse. Our people pushed back and said, “We can’t do this.” The ultimate solution was to partner with a nonprofit in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, to build the East Coast distribution center atop a reclaimed coal mine.

After at least three owners and multiple epic climbs around Argentina, a thoroughly loved Nano Puff® Pullover gets some well-deserved patches of honor. Photo: Tim Davis

In Mérida, Mexico, our supply chain partner turns factory scraps into recycled cotton yarn for Patagonia clothing. Photo: Keri Oberly

As important as focusing on emissions is, does that cause us to miss too much? Is decarbonizing actually a great way to clean up a company, or is it a red herring?

Not a red herring, but only a small part of the story, and offsets are an even smaller part. We could decarbonize the economy and still lose the Earth if we don’t address water shortages, habitat loss, species extinction. We need to use resources more efficiently and develop local circular economies in which one company’s waste can be another’s feedstock. In the rich world, too much is never quite enough. We need to meet our needs in a healthier way. Electric cars are great, but the ability to get around locally by bicycle or on foot is even better.

“That sense of agency is much more important than optimism. You make the change not because you think it’s going to be easy, or even possible, but because it’s something that has to be done.”

We’re a part of nature, plain citizens and “members of the biotic community,” as Aldo Leopold put it. We don’t live in an “environment.” We inhabit a home planet and, more narrowly, live with other species in a life zone that extends only 6 miles above our heads and another 6 below the ocean surface. The limits are real, so is the beauty of it.

Marketing Operations Manager Kyle Olsen wheels into work with son, Finn, who attends Patagonia’s Great Pacific Child Development Center. Ventura, California. Photo: Tim Davis

Do any recent environmental wins help reduce the environmental impact of our products?

We’ve seen progress on two important, long-fought fronts. First, getting “forever chemicals” out of durable water (and stain) repellent finishes without a major loss of performance. Ten years of research and testing by the GORE-TEX brand has yielded the first effective waterproof/breathable membrane for outerwear not reliant on PFCs. That’s major. Second, we’ve worked for years to address the problem of synthetic microfibers that shed in the washer, evade filtration in municipal water systems and make their way out to sea where they’re consumed by birds and marine life. Samsung accepted the challenge to develop a washer that can capture and process the waste. The technology is rapidly improving, and their competitors are following their lead. Meanwhile, we’re continuing the search for better fabric engineering and construction to reduce microfiber impact.

How has the role of business shifted post-pandemic?

The habit of innovation makes us more resilient than companies focused more narrowly on efficiency and profit. But an innovative culture relies on informal communications and collegiality—lunchtime bike rides together, picking up the kids from childcare at closing time, camping out Wednesday nights on Pine Mountain. During the pandemic we drew down our cultural capital, and we’re working to rebuild that now.

In San Vicente, Chile, Jacqueline Sangueza and Christopher “Caco” Clemo sort fishing nets for net-recycling company Bureo. Discarded, otherwise-polluting nets will be recycled into NetPlus® material and used to make clothing and other products. Photo: Jürgen Westermeyer

Has the responsibility of business changed since the pandemic?

The responsibilities haven’t changed, but you can see them more clearly. Business, like government and civil society, has an obligation to address our chronic, accelerating environmental and social crises—and at minimum, clean up after itself. It’s time to reverse the Milton Friedman doctrine, to say instead that the sole purpose of business is to meet human needs for food, clothing and shelter, while also giving back to communities and the natural world as much as we extract.

Are there more responsible companies now than 10 years ago?

Oh, yeah. The B Corp movement is on fire. The old guard is worried about reputational risk and eventually lawsuits for wasting the planet. Young people, as an exasperated college dean once told me, don’t want to work for bad companies.

What would a third edition of The Responsible Company say?

I’d hope to say that democracy is on the rise, inequality is on the decline, that we are learning how to make a living that allows the natural world, including humanity, to recover our bearings and thrive. I’m confident that we will have learned more at Patagonia about how to live and work sanely and be eager to share what we’ve discovered.

Sometimes I’m asked whether I’m an optimist or pessimist. I’m halfway on the spectrum, but I tell people the most pessimistic person I know is Yvon, who describes himself as a doombat. But that never stopped him from doing what he thought was the right thing to protect the natural world and help bring it back to life. That sense of agency is much more important than optimism. You make the change not because you think it’s going to be easy, or even possible, but because it’s something that has to be done.

Vincent Stanley hoists a Bureo® skateboard made from NetPlus recycled nylon. Photo: Tee Smith